Samia Halaby

Samia Halaby is an abstract painter, writer, scholar, and former professor. Originally born and raised in Palestine, her family was displaced during the 1948 Nakba. She came to the U.S. in 1951, originally in the Midwest, and has been living in New York City since 1976.

Abstract art is a major part of Halaby’s work, as she continually works to examine the different ways we can present and capture ideas or subjects.

One could argue that she’s the most impactful and prolific abstract artist of her time – but she’s much more than that. Her determination for experimentation has led to making thousands of works across paintings, computer art, sculpture, printmaking, drawings, photography, and more.

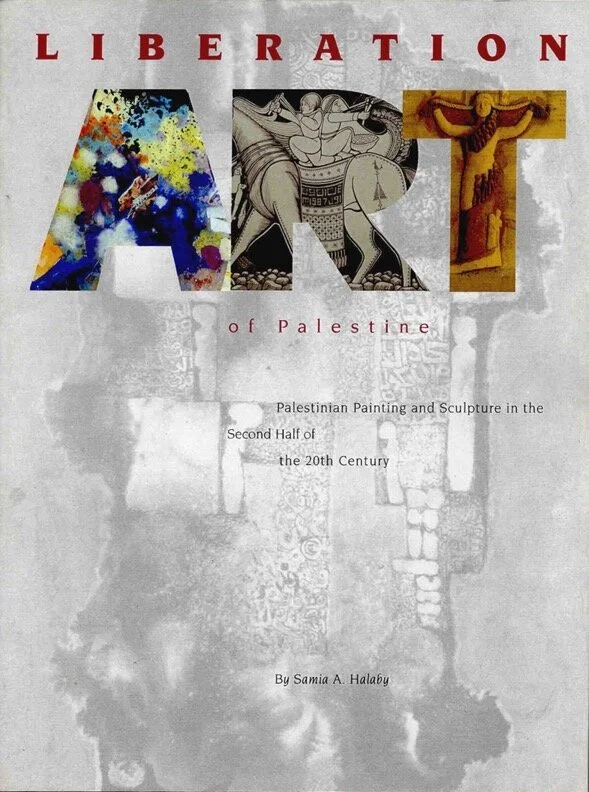

Halaby is also the author of the 2001 book Liberation Art of Palestine, a deep look at Palestinian art during the latter part of the century from 1948-2000.

Red and Pieces of the Sky, 2009

Quiet Fire in Blue Sky, 1999

All Blue, 1982

Yellow Dancing, 2011

Halaby was born in Al Quds (Jerusalem) on December 12, 1936, towards the end of the Colonial British Mandate of Palestine period.

“I remember the British soldiers, but I was not old enough to understand why they were there and what was happening. I do remember them being intrusive and examining our baggage,” Halaby said.

While she was too young to fully grasp it all, this was a crucial time. “I was born to the sound of these marvelous crowds, to the noise of revolution. My first three years of life were the years of the great Palestinian revolt and general strike from 1936 to 1939.” (Also known as The Arab Revolt.)

She spent her childhood in Yafa, but would go back to Al Quds every weekend to visit the rest of her family.

This included visiting her grandmother’s house, whose garden would serve as a later inspiration from its colors, shapes, and subjects.

Then in 1948 during the Nakba, Halaby’s family home in Yafa was robbed and occupied. The family fled to Beirut, Lebanon. “I was then almost 12 years old and just beginning to comprehend reality and my surroundings,” she said.

While her father returned to fight against the occupation, with hopes they could return, there was no such opportunity.

The family stayed in Beirut for a few years until 1951 and then moved to the US.

Fruits and Gourds, 1994

Speeding by, 2016

Jerusalem, My Home, 2014

I can see the Quiet, 2020

Volcano, 2015

The Halaby family ended up in Cincinnati, where a cousin was living at the time.

When first coming to the US, she found it difficult to adjust to and meet new people for the initial few years.

In the Midwest, Halaby found people were generally accepting and friendly. She also appreciated that it had a working-class atmosphere. However, there were also instances of racism that were new to her, like the pointing out of her “olive skin” at times.

When it came time to go to college a few years after arriving, her mother suggested she study art since it had always been something she enjoyed doing. Halaby took her recommendation.

“I go through periods when I wished I were a mathematician and asked myself why I studied painting,” Halaby said. “But, in school I used to get a headache every time I took a math exam – so I thought I am not going to live my life with a headache.”

Essence of Arab, 2007

Prancing In The Vineyard, 1982

Blue in Frames, 2010

Northern Migration, 2010

Halaby went to college at the University of Cincinnati School of Fine Arts at a co-op program, and she worked outside of school to support herself in getting an education.

After four years, she earned a Bachelor of Science degree in Design, which she had chosen since it would enable more professionally opportunities.

She then attended Michigan State University for a one-year program to get her Masters of Arts degree in Painting. This was around the time of abstract expressionism, where she had professors and visiting artists from New York who influenced her. Jackson Pollock’s brother, Charles, was also teaching there.

Halaby’s interest in abstract painting started to develop, at the time focusing on shadowy figures and landscapes. A few of the paintings formed her graduation show at MSU in 1960.

Upon then working as a designer back in Cincinnati for a year, Halaby realized it was not what she wanted to do. Instead, she wanted to be a painter.

Of course, she still needed to find a way to make money as well. She settled on the idea of teaching and went to get her Master of Fine Arts at Indiana University, a degree which was required for teaching at the college level.

At IU, over the two-year program, she found the mix of both practicing artists and art historians in the same department to have great interaction together.

Totems, 1961

Her practice of abstract art continued to develop. In a feature by Selections Arts Magazine, which has a comprehensive feature on her art education, Halaby said:

“In due time my love of art history began to guide me and encourage me to consciously adopt influences from the abstract and revolutionary art of the 20th century.

By my last year at Indiana University as a graduate student I experienced a breakthrough. I remember it as one of many which happened to me subsequently many times. Suddenly my hands and my intuitions knew what to paint in ways that converted conscious rumination into quiet, unquestioning certainty.

Untitled, 1963

The result of my breakthrough was flat colour paintings and I did many of them. I began to see that they were abstractions based on visual experiences of surfaces in our surroundings. In them shape, size, space, and colour were all relative. They were the paintings of my MFA exhibition at the Indiana University Gallery in 1963.”

Samia Halaby’s 1963 MFA show display at Indiana University

She also found herself even more intrigued by art history, thanks to a couple of wonderful lecturers at IU. Overall, Halaby was happy with her art studies across the schools.

Wilderness, 2015

Orange Kiss with Sky, 2015

Softness of Brow, 2015

Angel Man Holding His Seed Pods, 2021

After being finished with her education in 1963, Halaby soon jumped into teaching. Initially, she started instructing at the University of Hawaii Manoa in 1964, before coming back to the Midwest to teach at the Kansas City Art Institute, Indiana University, and the University of Michigan.

Kansas City Studio, 1966

Green Mirror Sphere, 1968 (at Michigan State University)

Less than a decade after graduating in 1963, Halaby was then hired in 1972 to teach at the Yale School of Art, where she became the first woman in the institution’s history to hold the rank of Associate Professor.

However, her time at Yale was marred by the academic environment. “The thick racism I felt emanating from most of my fellow professors and from the administration was really very unpleasant and very backward,” she said.

The cherry on top came in 1982, when she was fired after the school denied her tenure after 10 years.

Students came out in support of Halaby after the announcement. In response, Halaby and a committee of students launched the “On Trial: Yale School of Art” exhibition to criticize the university.

Halaby filed a grievance and won, but was told “You can have your job back if you prove you're the world's expert at what you're teaching.” She didn’t go back and said that separating from Yale turned out to be the best thing that happened to her.

Halaby working on the ‘For Ni’ihau from Palestine’ installation, 1985

Halaby did some more teaching over the years, such as notably in 1985 at the University of Hawaii, Manoa.

While there, Halaby made a large-scale installation painting at a faculty exhibition, and later a small book, to honor the locals and make the connection to colonialism.

“Both are dedicated to the Hawaiian people and to the working-class in Hawaii. This dedication resulted from my experience as a Palestinian,” she told Artnet. “I know the pain applied to oppressed nationalities. I needed to express my sentiments in this way so that I could attain a degree of honesty while enjoying life on the beautiful land of the beautiful Hawaiians."

Green Earth, 2014

Transparencies, 2017

Our Beautiful Land of Palestine Stolen in the Night of History, 2016

In 1976, Halaby moved from New Haven to New York City. Since SoHo was too expensive for her at the time, Halaby found a loft space in Tribeca instead to live and have her art studio.

She found the art world in New York to not be a welcoming environment as a Palestinian, an Arab, an immigrant, and a woman. Her work was often rejected. Even with other artists, she found it to be competitive instead of collaborative.

Halaby took the initiative to convert her loft into an exhibit-like space where she hosted hosted cultural evenings that included both paintings – from a wide group of international artists – as well as poetry readings in both English and Arabic.

Yet as more time went on, she still found herself closed out from New York galleries.

In 1989, Halaby had paintings featured at the third biennial of Havana, Cuba. She went to attend and saw many exhibitions rom around the world, including Africa and South America. And while the Western art world shut off Palestine, the working-class in Havana embraced it.

During the early 1990s, Halaby was part of a group called Arab Women Artists that sponsored shows and performances by Arab artists.

She continued to take matters into her own hands. In the early 2000s, she was involved in curating several exhibits,

This included serving as the senior curator for the Williamsburg Bridges Palestine exhibit in NYC in 2002 – a month-long exhibition of Palestinian art and culture from 1960 to the present featuring the work of around 50 Palestinian artists. Mediums included paintings, drawings, photography, video/film, installation, calligraphy, henna, dance, music, poetry, and more. Halaby traveled to Gaza, the West Bank, and the Palestine ‘48 territories to collect the art for the show directly.

She was also a lead curator for the Made in Palestine exhibit in Houston, Texas, in 2003 – the first museum exhibition in the US. devoted to the contemporary art of Palestine. It also focused on Palestinian artists still in the homeland at the time, with additional work by those in the diaspora.

Third Spiral, Dark Center, 1970

Slicer Waves, 1973

SIlver Rule, 1979

Aluminum Steel, 1971

Water, 1974

Mars, 1977-1978

Fire, 1975

Helical drawing, 1972

While she was teaching for her job, Halaby continued to make personal work. She was always interested in abstract art.

A few years after graduating, Halaby had taken a trip to visit her birthplace, Al Quds (Jerusalem), in 1966 – only a year before the 1967 Naksa resulted in the occupation of the West Bank.

Throughout, Halaby saw many of the mosques, and their panels, which she admired and took photographing them for later reference. This included Al-Aqsa Mosque and the Dome of the Rock there. During the trip, she also visited Istanbul and Syria.

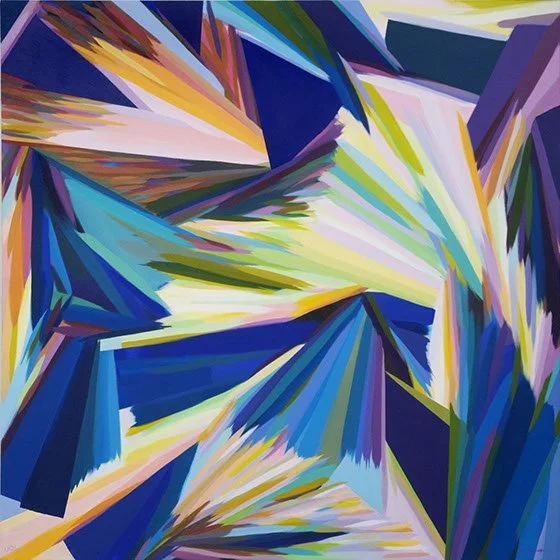

With inspiration from that trip, Halaby focused on a series of experiments from 1966-70. She created a series of geometric still-life works to try out variations on how a three-dimensional object can be communicated on a two-dimensional surface.

This interest and studying of geometry would continue throughout the 1970s, and for decades to come, as part of her abstract art path.

“I choose abstract painting because for me it is the most advanced way of thinking about pictures…

The most advanced language of pictures was invented at times of working class revolution. That includes the Impressionists, the Soviet Suprematists, the American abstract expressionists. And so they’re all abstract.

And abstraction is very interesting, it doesn’t force anyone to make pictures that praise a ruling class. You can explore ideas and forms and patterns in nature, you can be a mathematician, you can expore the nature of space. So it’s a much more open world.”

Growing Shapes and Centers of Energy series, 1986

Autumn Leaves and City series, 1982

Growing Shapes and Centers of Energy series, 1989

Halaby had wanted to figure out her own language of abstraction without the influence of academic perspectives on her artistic practice.

This involved continued experimentation. In one below example from a series of the early 1980s, Autumn Leaves and City, she decided to not use a brush but rather try it with a palette knife, wanting to find a new way to bring about the essence of the life cycle of the world featured.

Autumn Leaves and City Blocks series, 1982-1983

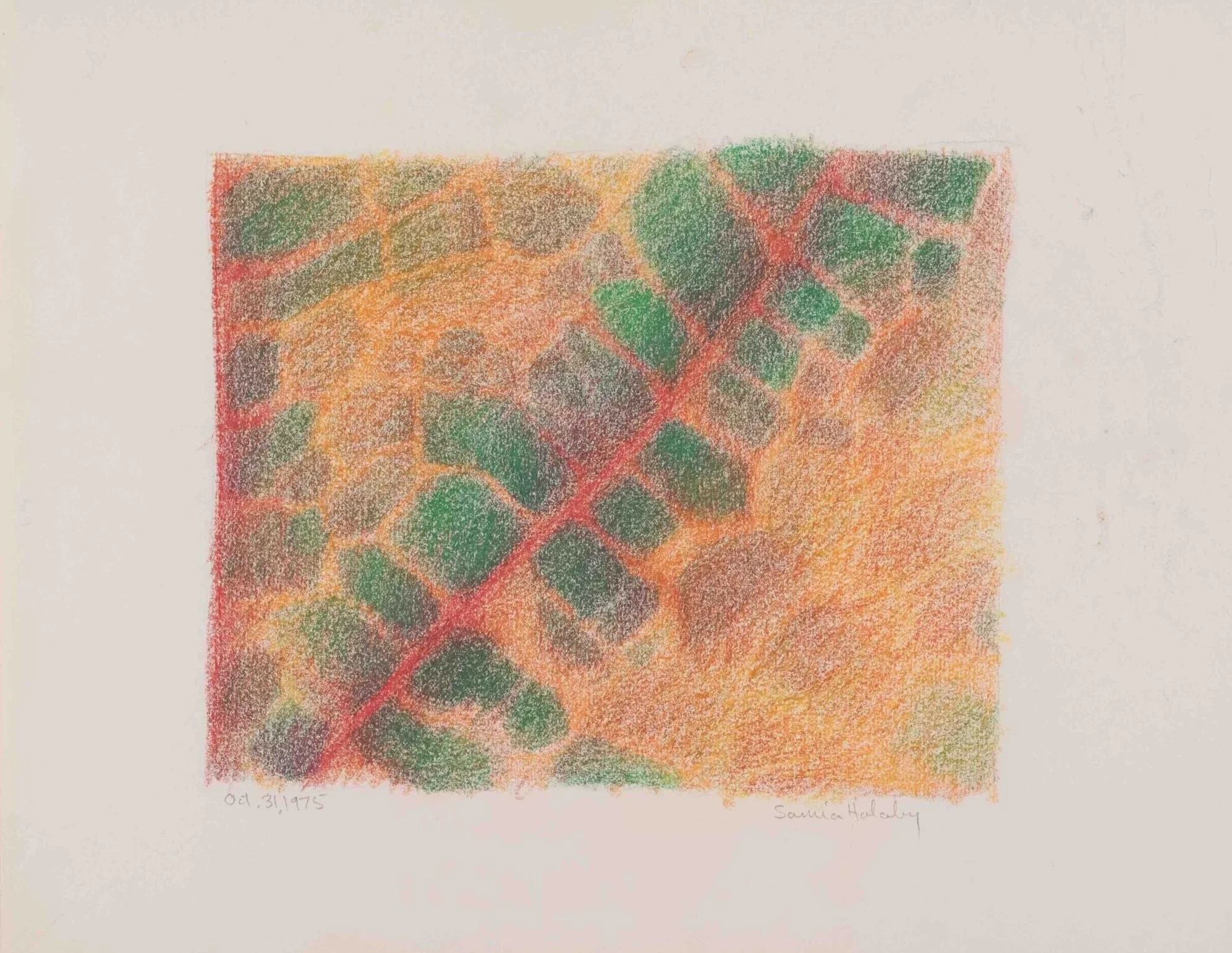

The series, which she did from 1982-83, had grown out of a set of initial tests in 1975, when she had still been living by Yale in New Haven, Connecticut, and was trying to figure out how to best capture the colors and life of autumn leaves.

Autumn leaves colored pencil test, 1975

During 1984, Halaby started working on another series titled Growing Shapes and Centers of Energy. This body of work would go on until 1992.

Growing Shapes and Centers of Energy series, 1986

Later, in the 1990s and 2000s, Halaby’s painting style moved away from typical geometric shapes and relied more on smooth vibrant brushstrokes, representing how vision settled on different objects and wanders around surroundings.

In addition, she worked on a project at this time with Palestinian artist Vera Tamari and students at Birzeit University in Ramallah that involved developing a system of cutting and stitching pieces of canvas to create hanging sculptures. She would go on to explore this more in her personal work as well.

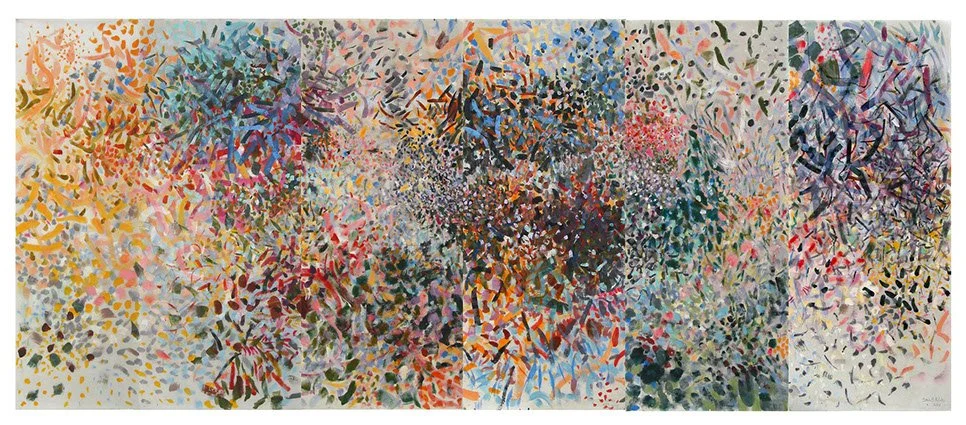

Jllayq, 2000

Palestine from the Mediterranean Sea to the Jordan River, 2003

Artist context (as told to tribes.org):

“The center section was very much above the mountains of Palestine and the extreme right was above the coast, I decided to make it a map of Palestine in textures. So the extreme right is the sea coast of Palestine, and the plain by the seacoast there is a lot of flora, wildflowers, gardens and stuff like that. And my memory of them, especially from the town of Yafa, which was a famous port city. It's abstract of course, and as an abstraction it describes different things at the same time. So there are stones, the feeling of the distribution of stones, the roughness of the fig tree, the shape of olive trees, and on the extreme left there are hints of the towns and cities, towards the desert, and then the desert. So it's a map of Palestine, so I called it a very political title, indicating that I don't think Israel should exist as a fascist, undemocratic, patriarchal state because it does not believe in equality, and it does not have a separation of church and state. So I believe in a Palestine that is democratic with equality for everybody, which is why I called it ‘Palestine, from the Mediterranean Sea to the Jordan River,’ which includes all occupied territories, old and new occupations.”

Outside of painting, Halaby has always sought to embrace technology and experiment with new techniques and possibilities.

In 1985, she purchased an Amiga computer on sale and began teaching herself computer programming in order to independently discover the nature of this new technology.

She knew from her studying of art history that great artists always embraced the latest technology, which could lead to interesting results. Art had to move forward and be pushed, the bounds tested.

The Amiga 1000, originally released in 1985

Halaby’s interest with computers in particular was decades in the making, as told to Right Click Save Magazine:

“I graduated in 1963 with an MFA in painting from Indiana University at a time when there were only big monster computers. I can remember visiting an exhibition by IBM sometime during my student years that had a huge influence on me, imprinting my brain with permanent excitement for all things digital. My friends in the Computer Science department would discuss their experiences programming the university’s mainframe computer with white punch cards.

My next fascination was with Sketchpad — a program written by a graduate student at MIT in 1963. Back then, my work was based on perspective and I was making paintings of geometrical still lifes, so the idea that a computer could work in 3D and rotate objects was exciting.

When I ended up returning to the university as a professor in 1971, I was invited to join the computer lab. But then all of a sudden an academic position opened up at Yale University, which closed the door on the enthusiasm that had been slowly building.

I ended up buying an Amiga 1000 at a blowout sale (1986). It had obviously underwhelmed the financial community, but to me it was magic. I sat at home with my two manuals and got lost in a new world of thought. For three years, all I did was program that computer, making abstract paintings that I term ‘kinetic painting.’ My aesthetic life had shifted.”

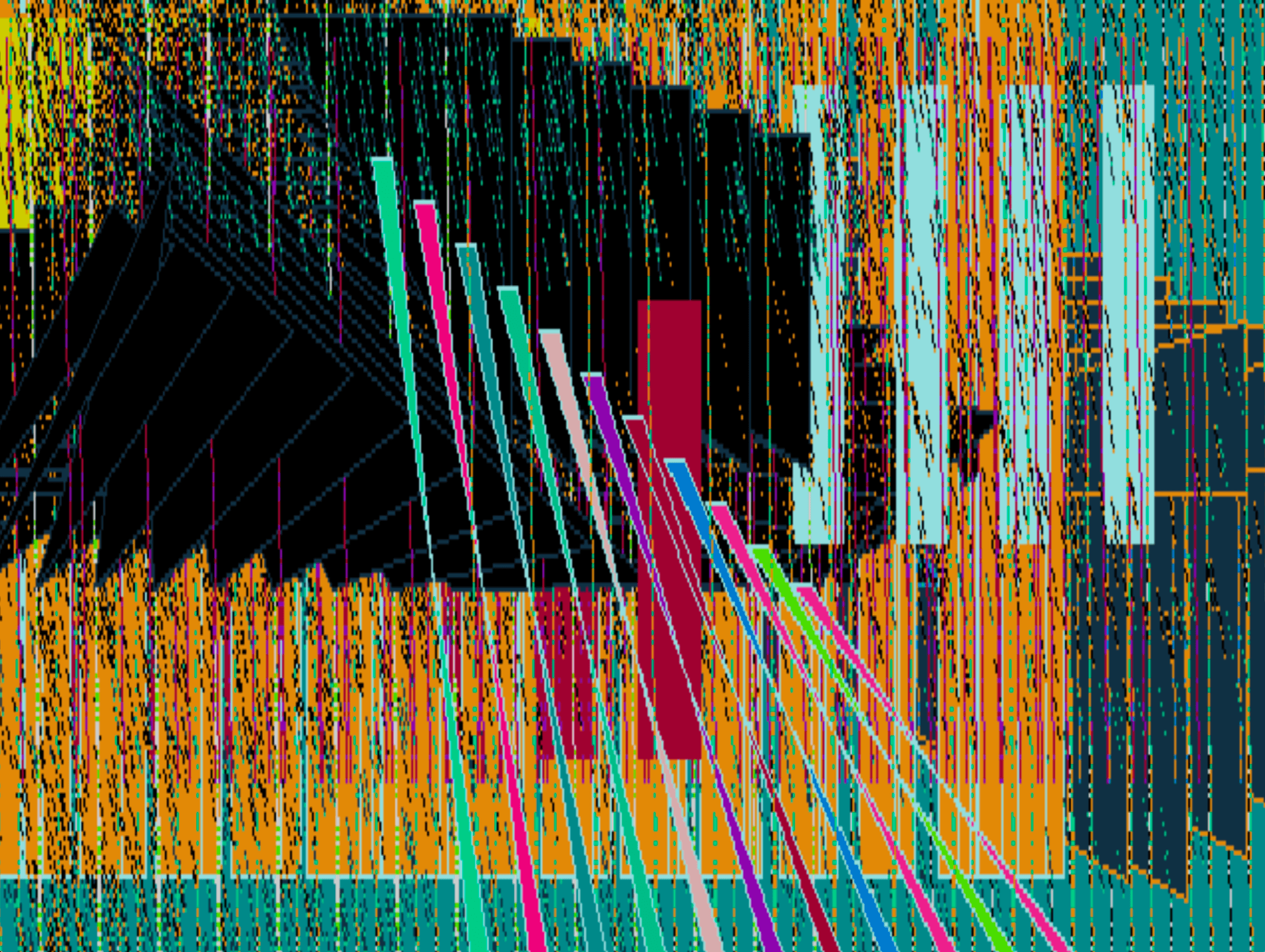

Still from Bird Dog, 1987-88

With this computer-based kinetic art, Halaby said she didn’t want the programs to decide the aesthetic forms she would use. Instead she was determined to not just use the software but program the languages.

In learning to program, Halaby realized she could create paintings that moved and grew. Plus, she could sounds.

In one project, she created a program that brought together geometric shapes with motion and sound to create “kinetic paintings.”

When Halaby attended conferences of the Small Computers in the Arts Network (SCAN) in Philadelphia in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the other attendees happened to be mostly musicians, who would jam on stage after meetings.

Through making her Kinetic Painting Program, Halaby was able to make the live keyboard notes into an “abstract painting piano” that she could manipulate in real time, bringing in different colors or patterns as musicians played. It was a shared, mostly improvised experience.

The practice of working with musicians continued at home in New York City as well.

In the 1990s, this evolved into a collaboration where Halaby did live art performances in NYC alongside musicians Hasan Bakr and Kevin Nathaniel as part of The Kinetic Painting Group.

Overall, it ended up being a challenging but fulfilling proces for Halaby to try her hand at.

“What I discovered was that the computer had the potential for other exciting things. I can make something abstract that can also have motion.

However, I was not interested in the kind of motion that came as a result of a lens-based video or camera because that takes you back to perspective, which to me is an earlier technology that painting has amply explored.

I am more interested in the relatively of space, time and color. To have those elements but also to allow them to grow and change and shift, as well as combining them with sound, was interesting.”

Yafa, 1991

One notable effect also came in how digital changed her view on colors:

“The major influence the computer had on my painting was that it improved my color. On the one hand I was looking at this luminous screen and then on the other these dull paintings. And I thought: ‘Samia, you can make them brighter.’

But the process is the same. If I put a stroke on a painting, I’m still walking back and forth all the time. With the computer, it’s the same — adding and subtracting — the only difference is I’m sitting down.”

She focused on these kinetic pieces until 1995, in particular, but continued to make digital work in its spirit over the years since. Even recently, she created a self-programmed software art piece for the Taipei Biennial 2023 opening program, in collaboration with musician Togar.

Bird Dog, 1987-88

Flowers, 2015

Wind in the Sun on Earth in Early Winter, 1982

Mountains of Palestine, 2000

Angels and Butterflies, 2010

Growing Wild, 2010

Her interest in technology also had Halaby ahead of the curve on having her a website page, as early as the 1990s – complete with her work and essays of her paintings or memories of Palestine. It’s still up to this day.

At this time, she was making more frequent trips back to visit Palestine, where she would meet other artists and put interviews on the site as well.

Part of the impetus for this came from her friendship with Mona Saudi, a Jordanian sculptor who headed the Plastic Arts Section of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). They had met in 1979 while Halaby had been visiting Beirut, and Saudi would go on to introduce her to other artists.

Palestinian painter and friend Sliman Mansour noticed Halaby had taken this interest in other Palestinian artists. At the time, he was leading the Al-Wasiti Art Center in Al Quds.

In 1999, Mansour asked Halaby if she was interested to take on an an assignment for the center: drive within the Palestine ‘48 occupied territories and speak with more artists to create a 40-page paper.

Halaby agreed, but she ended up interviewing 46 artists – so the paper eventually turned into a book. As part of the process, Halaby read any printed material she could find on Palestinian art history. The goal was to combine her field research with an international historical context.

In 2001, the book was released. Liberation Art of Palestine: Palestinian Painting and Sculpture in the Second Half of the 20th Century focused on the period post-Nakba until the turn of the century.

Untitled, 1982

Foliage, 1994

Mountains Between Birzeit and Ramallah, 2015

Blue Tulips, 2010

Green for Palestine, 2009

Her efforts to preserve Palestinian history also extended into another type of artistic pursuit: documentary drawing.

This had started with the Olives of Palestine series that she began in 1996 and really worked on more in 1999 when staying in the country for several months.

Also in 1999, Halaby started work on what would become a more expansive project – documenting the The Kafr Qasem Massacre of ‘56 through her own drawings.

The massacre was an attack on 49 civilians, martyred on their way home from work after a last-minute curfew was imposed. Kafr Qasem was one of the Palestinian villages occupied in 1948, which also meant that technically those Palestinians were considered to have citizenship within the so-called “State of Israel.”

Halaby started this project after meeting Aishy Amer, a daughter who had family from the village.

They went and visited the village together, where Amer introduced her to a local group of five extended Palestinian families. Over time, she built their trust and continued to seek their input on making the drawings as realistic as possible.

Halaby interviewed many people of Kafr Qasem and also found a valuable historical resource in the locally published magazine, Al-Shorok, which had many specific details and interviews with locals from the time.

She grew to feel compelled to create multiple pieces to more fully tell the story. Halaby told Jadaliyaa about the process:

“When I first accepted the challenge of drawing the Kafr Qasem massacre, I wanted to represent its events as though I were a camera on site. Documentary drawings, I thought, could recreate what photography might have given us if done on a historical basis.

I would learn all I could and present the specific individuals and the documented events. I worked on the project in three major periods, each occupying most of a year or several years.

I began work in 1999 and continued into 2000. In 2006, on the occasion of the fiftieth memorial of the massacre, I created both a web page and an exhibition of the drawings.

In 2012, I returned to the project with the intention of finalizing it by making large-scale drawings and developing a book.”

The book ended up releasing in 2016, simply titled Drawing the Kafr Qasem Massacre.

Selects from The Kafr Qasem Massacre series, with context

Site note: Middle East Monitor also did a great video with Halaby about it.

Artist Caption (as told to Jadaliyya):

During less than two hours on 29 October, 1956, Israeli Border Police killed forty-nine people in the Palestinian village of Kafr Qasem. They were mostly workers and children returning home in the evening. Most were killed on the western entrance, while inside the village it began when eight-year-old Talal Easa went out to retrieve a goat after the suddenly announced curfew. Talal’s father, Shaker, heard the shots and dashed out to his son. He was also shot. Talal’s mother, Rasmiyya, and, right after, Talal’s teenage sister, Noor, ran to their bleeding family and suffered the same fate. They remained where they fell, bleeding until morning when they were hauled off by truck to a hospital. Talal died. The grandfather, Abdallah Isaa, then ninety years old, was left alone and saw the massacre of his family. The following morning, Abdallah was found dead.

Artist Caption:

In the northern fields of the village, three shepherd boys were out watering the family’s flock of sheep not knowing that Israel had launched a surprise attack on Egypt just hours before, nor did they know of the curfew imposed on their village. The oldest boy, Abdallah Easa was sixteen and the youngest, Abed Easa, was nine years old. Ibraheem Easa, their uncle who was thirty-five years of age, had learnt of the curfew and left the safety of his home to bring them back. They returned immediately with Ibraheem leading. Abed and Abdallah were just behind him while the third boy, Sami Mustafa, was watching the rear of the herd. The boys were met by Israeli soldiers of the Border Police, who immediately shot and killed Ibraheem, Abed, and Abdallah. Sami saw them being shot and fell to the ground, played dead and survived.

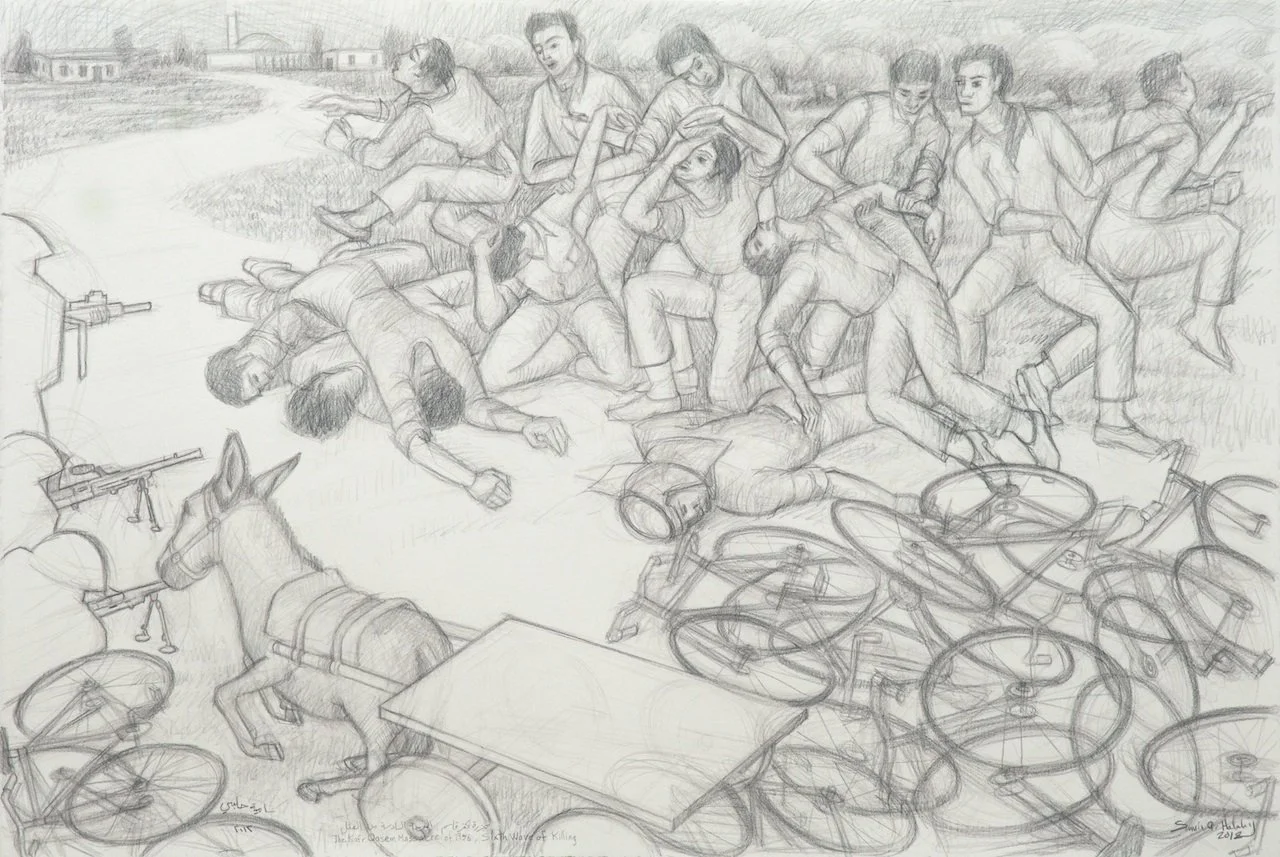

Artist Caption:

Five minutes before the curfew, and unaware of it, four quarry workers were returning home to Kafr Qasem on bicycles. When confronted by Israeli soldiers, with whose harassment they were familiar, they reached for their identity cards. Instead, an order to "harvest them" was given. Two, Ahmad Freij, age thirty-five, and Ali Tah, age thirty, died. Both were fathers of young children. Two others, Mahmoud Freij and Abdallah Badair, managed to escape. Mahmoud was wounded in the thigh and managed to crawl to an olive tree and hide until morning.

Artist Caption:

The twelve-year-old shepherd boy, Fathi Easa, was leading his family’s herd of black goats home after pasture. His father was driving the herd from the rear having heard of the curfew and had come to hurry his son home. There were three weapons in the hands of the Israeli Border Police all aimed at the boy, an Uzi, a Bren, and a rifle. All were fired, and the boy collapsed and died.

Artist Caption:

Evening was darkening as the Israeli Border Police ordered thirteen or more workers to lineup on one side of the road. They had arrived on bicycles and a mule wagon. One of the workers, seventeen-year old Saleh Easa, had arrived with his two cousins. They had heard about the curfew and only feared a beating. When the execution style shooting began six fell dead. Saleh, wounded, playing dead, was dragged to the pile of bodies. He remained quiet, gritting his teeth in spite of extreme pain. He witnessed the rest of the massacre and later crawled to safety.

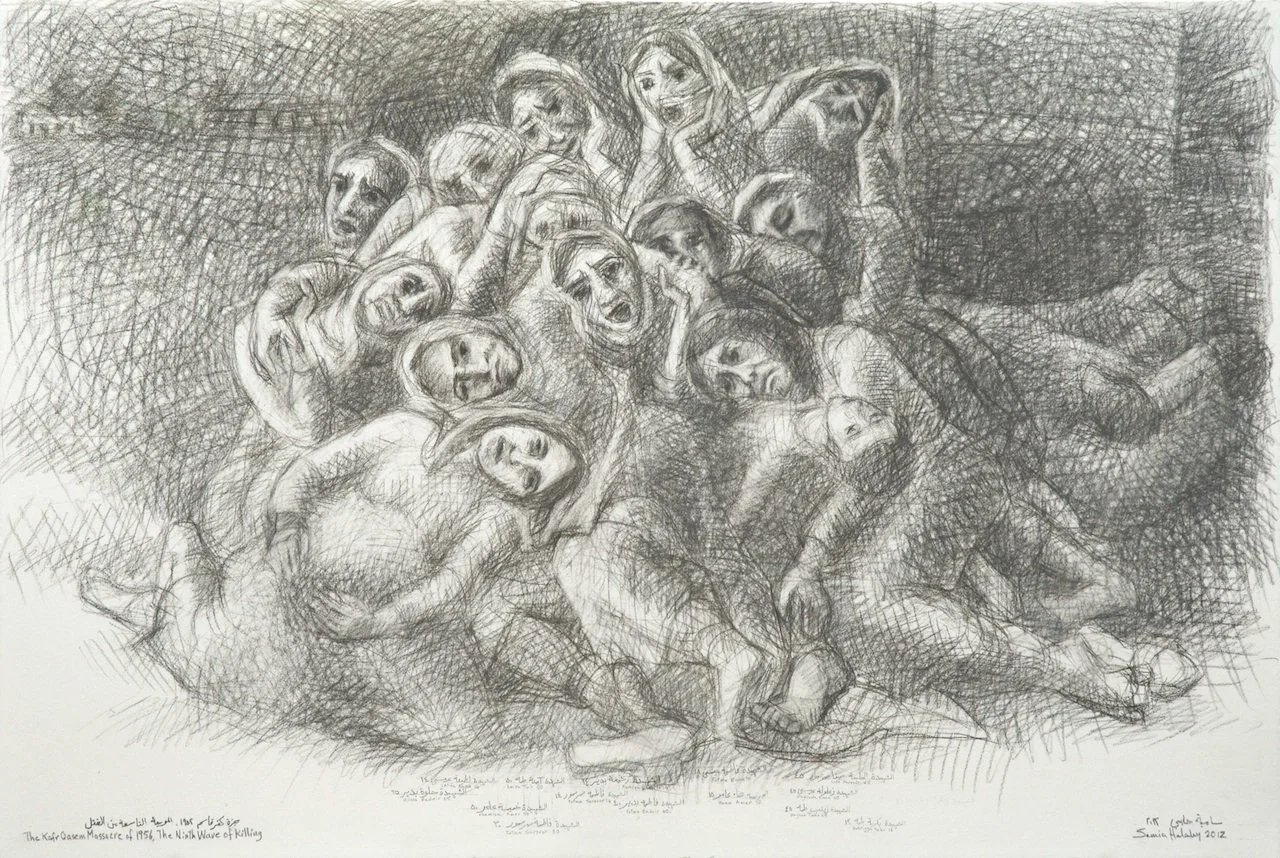

Artist Caption:

Night had fallen when the truck arrived at the location of the massacre. Among the victims of the ninth wave were two men in the cab of the truck and fourteen women with two boys in the back. The driver, seeing the scattered dead, tried to escape at high speed. This interrupted the singing women, who unwittingly began to scream, thus alerting the recumbent soldiers resting at the school’s well. The soldiers ran after the truck, shot its tires and gas tank, and stopped it. Safa Sarsour, having just seen her sixteen-year-old son, Jum’a, dead on the side of the road, now witnessed her second son, fourteen-year-old Abdallah, being killed with the men. The women, some pregnant, elders and girls, pleaded for their lives. The only survivor was Hana’ Amer, fifteen years of age, who said that the women clung to each other for protection, even the two girls who had managed to escape returned to the circle. As they were being shot, they turned in a big group and one by one they fell. The soldiers continued shooting into their heads to insure their death. How does it measure western civilization when soldiers of the Israeli border police line up defenseless women—some pregnant, tired, returning home from work—and kill them with cold deliberation?

By the 2020s, Halaby’s work had been acquired by museums such as: the Art Institute of Chicago, the British Museum, the Guggenheim Museum (New York), the Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris, and the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington D.C. Yet at the same time, none of those art institutions had even given her a solo exhibition.

The first Western retrospective of Halaby’s work was scheduled to open at her alma mater, Indiana University, on February 10, 2024.

Around a month before, however, she received a two-line note from the director of the university’s museum canceling the show, which had been years in the making. This was later said to be due to “safety concerns” as IU claimed the show would be a “lightning rod” and could cause trouble.

The exhibition was also accused of carrying an antisemitic undertone. The museum director, David Brenneman, reportedly expressed concern to employees about Halaby’s social media posts, where she had expressed support for Palestine and called the attack on Gaza a genocide.

Ironically, just a few months earlier, Brenneman had applauded Halaby’s “dynamic and innovative approach to art-making” in promotional materials, where he said her exhibition would demonstrate how universities “value artistic experimentation.”

Worldwide Intifada, 1989

The retrospective, which was to open Feb. 10, had taken more than three years to organize – in partnership with Michigan State University’s Broad Art Museum. Agreements were already signed with grant-making foundations and museums that lent artworks to Indiana University from around the country.

Halaby was also preparing to unveil a new digital artwork for the exhibition, in addition to previously unseen works – like a 1989 abstract painting, titled Worldwide Intifada.

For Halaby, who was raised in the Midwest, the cancelation was a rude awakening. “I thought I had found a little bit of something I could call my home in Indiana,” she later said, “and it turned out to be totally false.”

Students protested the decision – and over 15,000 people signed a petition – asking for the retrospective to be reinstated at IU:

“In the absence of any response from the administration, it is apparent that the University is canceling the show to distance itself from the cause of Palestinian freedom.

For 50 years, Samia has been an outspoken and principled activist for the dignity, freedom, and self-determination of the Palestinian people.”

During the Gaza Solidarity Encampments movement during Spring 2024, the same Indiana University brought in snipers on the roof of school buildings to be used against students who had set up their own encampment. No one was fired at, thankfully, but it was part of a broader effort to silence students who had been protesting for Palestine. This is a noteworthy line to draw to the students’ statement about Halaby’s exhibit, further demonstrating the university’s aversion to Palestinian liberation and anyone who speaks up for their rights.

It wasn’t only students either – IU faculty arranged a teach-in called “Warning! Dangerous Art!” and the local Bloomington community also held an “Uncanceled” event to teach people about her life and work.

The retrospective had been previously arranged to travel to Michigan State University’s Broad Art Museum in June, and that part of the plan was not canceled – MSU’s Broad Art Museum remained committed to keeping that as scheduled. Samia Halaby: Eye Witness opened there on June 29, 2024, on view for the rest of the year. It’s Halaby’s first American retrospective.

Thunder Meandering Space, 2010

Variable Motion, 1993

Pyramid, 2011

Position Slide, 1980

Position Interplay, Light, 1980

Halaby was also involved this year in another exhibit that ran up against the walls of the art world.

At the Venice Biennale in Spring of 2024, the Palestine Museum US submitted an exhibition for approval. It was called Foreigners in their Homeland: Occupation, Apartheid, Genocide, which was a response to the biennial's theme of Foreigners Everywhere. However, it was rejected.

So instead, the Palestine Museum US arranged for the exhibition to be put up right nearby the Biennale grounds instead, running for the same duration of time, featuring the work of 26 Palestinian artists, including two artists in Gaza (including Maisara Baroud).

Halaby debuted a new piece for the exhibit: Massacre of the Innocents in Gaza, which is over 10 feet wide.

Massacre of the Innocents in Gaza, 2024

At the end of November 2024, an exhibition entitled Electric Dreams opened at the Tate Modern in London, about art and technology before the internet, which includes Halaby’s kinetic paintings that she made between 1990-1996.

Today, Halaby still lives in the same NYC loft that she moved into in 1976 – coming up on 50 years. She still finds it to be difficult in the local art scene as both a woman and a Palestinian.

If she had her wish, for Palestine to be free from occupation, she would live in Al Quds, her birthplace.

In an interview with Palestine Museum US, she said:

“My contribution to Palestine probably is that I don't keep my mouth shut (laughs). I express my political views. I am determined that I connect Palestine to my artwork. Wherever my artwork goes, Palestine goes with me. My hope for Palestine goes with me. My hope for Palestinian children will always be connected to my legacy.”

In 2019, she started the Samia A Halaby Foundation, a nonprofit started in to benefit working-class Palestinian children and women living within the borders of Mandate Palestine.

Halaby remains fairly active on Instagram, where she has often asked for feedback from followers and friends about in-progress paintings.

Peacock of the Sea, 2022

Shadows of the Sun, 2022

Six Golden Heroes, 2022

Untitled, 2023

Mila (unfinished, 2023)

Last Updated

November 2024

Image sources

Artist website

Artist Instagram @samalahalaby

Artist rep: Ayyam Gallery

Info Sources

Jadaliyya

Artnet

Right Click Save Magazine

Arab World Art

Taipei Biennial

Artland

Selections Arts Magazine

The New Arab

ArteEast

Bespoke

Jerusalem Story

ArtNews

MSU - The State News