Sliman Mansour

Sliman Mansour is one of the most well-known and accomplished Palestinian artists.

His work emphasizes Palestinian culture, history, and traditions – especially to the land and native trees such as olive trees or orange trees. You can also see it in his paintings of Palestinian villages or of women in traditional embroidered dresses.

Facing continual repression and Israeli confiscation of art, or closing of galleries, only fueled Mansour and his fellow artists’ further. Their work has become a national visual identity for Palestinian life and resistance, celebrating the rich heritage while acknowledging the pain and suffocating life under occupation.

“I believe in art as a social instrument, not as decoration for wealthy people’s houses,” Mansour said in a February 2024 interview with Al Jazeera.

Mansour has also been a leading member of artist groups and organizaitons over the years, including the League of Palestinian Artists, New Visions Movement, Al Wasiti Art Center, and International Academy of Art in Palestine.

This page mainly features Mansour’s painting work, but he has created art across mediums – including mud, starting during the first Intifada as a way to boycott Israeli goods and use natural materials.

Desert Tunes, 1977

The Scream, 1982

Alleys of Al-Quds, 2009

Palestinian village, 1983

Sliman Mansour was born in 1947 in the Birzeit town of the West Bank, just north of Ramallah.

His father and grandfather passed away when he was just a few years old, leaving Mansour and five siblings alone with their mother. She sewed clothes to make a living for them.

He spent his childhood there before later spending time of his adolescence in Bethlehem and Jerusalem.

His grandfather had built a house in Birzeit away from town, in a land full of vineyards, olive trees, and water springs. These would later show up in his work, especially the olive trees.

"I remember when I was 12, my grandfather bought a piece of land. He didn't measure it with dunams or acres, he would say I bought 53 olive trees," Mansour told Middle East Eye.

Mansour’s single mother put he and his siblings in a boarding school for orphans in Palestine, which was funded by German Churches.

“It was in this school, through a German house-father who was an artist, that I developed my artistic talent,” Mansour said in an interview with Caravan. He had joined the school’s art club.

That teacher would be important in several ways. For one, he submitted Mansour’s work for a United Nations Children of the World art contest, which a young Mansour won in 1962.

Mansour received a $200 cash prize, a lot of money at the time. But it also got him respect. “Soon, everybody in my school saw me as the artist of the school, and even of my town, Birzeit,”

The teacher also showed him other art that inspired him, as well as organizing camping trips to many places in Palestine that Mansour says increased the understanding and love for his country.

Harvest, 1977

Harvest, 1985

Harvest, 2014

Jerusalem rooftop, 2009

The predator, 2012

Initially after finishing his time at school, Mansour worked to save some money and was planning to come to the U.S. to study art.

After the 1967 Al-Naksa, an Israeli invasion that led to the occupation of Jerusalem and the West Bank, that was no longer going to happen. Mansour’s life was changed.

Mansour did find an art college he could attend at the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design in what became Jerusalem.

In the classes, his teachers tried to impart the lessons of abstract expressionism, a popular style at the time. However, Mansour wanted to paint realism instead.

He studied at the Bezalel Academy for three years, but did not finish due to financial and personal reasons.

The Naksa also made a big shift in Mansour’s point of view. In a 2018 interview with Qantara, he said:

“For a long time I didn't know much. We were under Jordanian rule and they taught us as children that we were Jordanian: the Jordanian flag is our flag, Jordanian King Hussein is our king. It was brainwashing.

When I became a teenager, I started to read the newspaper and I became a fan of Gamal Abdel Nasser (the pan-Arab nationalist and president of Egypt from 1956-1979). School friends also told me things. And then after the occupation happened, ater '67, I met Palestinians in Israel and everyone had their own sad story. It affected me a lot.”

Prisoners' day, 1980

Colors of hope, 1980

Prison, 1982

Al-Quds - Jerusalem, 1983

Battir village, 1983

In the 1970s, Mansour started to make artwork and brought in symbols of Palestinian identity, culture, and history.

Using symbols of ancient culture and the landscape of historic Palestine, Mansour wanted to embody the national culture and history. "As artists, we started to search for images to reflect identity," he said.

One of those symbols is olive trees. “When the Israelis occupied our land they started planting (non-native) cypress and pine trees instead of olive trees to change the landscape," Mansour says.

Another kind of tree has also played a role: "When I paint orange trees I am painting land that was occupied in 1948, and when I paint olive trees, I am painting about land that was occupied in 1967.”

Upon graduating university, Mansour started to meet fellow artists. Not long after, at 26 years old, he co-founded the League of Palestinian Artists – also referred to as the Rabita in Samia Halaby’s book – alongside Nabil Anani and Issam Badr. In total, there were around 18 artists.

Mansour said that their subjects included prisoners, martyrs, the earth, Al Quds, land confiscation, eviction, sumud, and roots.

Halaby writes about the group as those reclaiming their voice and land:

“When artists of the Rabita discussed heritage, they concluded that it can only provide form (tashkeel); and that the content had to come from their own contemporary surroundings.

When members of the Rabita agreed that they would paint the Palestinian village, it was not only to combine tradition and contemporary content, but also to take back their own cultural heritage.

It is a declaration of artistic war against the Orientalist Painters who came to Palestine as part of the colonization process to paint what is to them the quaint villages of 'The Holy Land.’

Members of the Rabita carried their supplies and traveled to villages, working directly from nature. The return to the village was a return to undamaged Palestine. Sliman Mansour remembers disregarding factories or high-rise housing while painting villages.”

One important first step was printing posters, which they thought was the best way to showcase their art and make it available.

A popular poster of Mansour’s was of his Camel of Heavy Burdens painting from 1973, which was printed for the first time in 1975. Featuring an elderly man carrying the city of Al Quds, and the Dome of the Rock, it remains one of his most well-known works.

Camel of Heavy Burdens, 1975

Orange pickers, 1979

Orange pickers, 1984

Olive Field, 2020

Settlers passed by, 2019

Olive harvest, 1988

Woman picking olives, 2018

In 1976, Mansour created the Bride of the Homeland painting of schoolgirl, Lina Al Nabulsi, who had been martyred. On her way home from school in uniform, she had joined a protest in support (which was common for students to do). Israeli Occupation Forces decided to chase Al Nabulsi and her friends into a building, where she hid under a table. The IOF then martyred her in cold blood.

Bride of the Homeland, 1976

“At that time, all the photos that were taken of her when she was killed were confiscated by the army,” Mansour said. “They didn’t want to show her dead. So I thought, ‘I will paint her.’”

This was also distributed as a poster for a limited time before the Israeli government confiscated both the original painting and all poster copies.

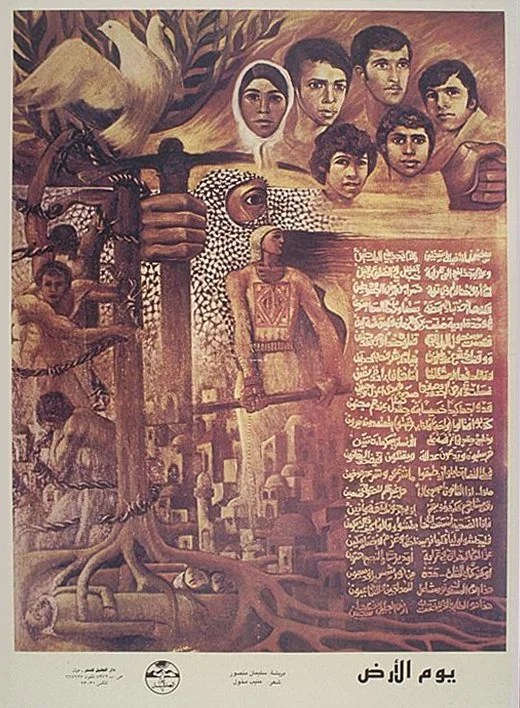

Another poster Mansour did in 1976 was for the first ever Land Day where Palestinians protested the confiscation of 5,000 acres of land and six unarmed civilians were martyred.

Yom Al Ard (Land Day), 1976

Site note: The Palestine Poster Project believes this be the first ever Land Day poster. Their archives have a collection of 300 and counting Land Day posters that followed, which is still only a portion of the actual total.

Palestinian landscape, 2010

Streets of Jerusalem, 2012

Mother and child, 1983

Overlooking an orange grove, 2021

Embrace, 2003

Olive pickers, 2013

Part of the reason why posters had been important was because there had been no galleries or museums active at the time, but they also hosting exhibitions in major Palestinian cities.

The Rabita, or the League of Palestinian Artists, held first fair in 1975 and took it across Al Quds / Jerusalem, Ramallah, Nabulus, Nazareth, and the Gaza Strip. Mansour and fellow artist and Vera Tamari later said this exhibit was a landmark in the formation of a popular art movement in Palestine.

Mayors of the local villages at the time – like Karim Khalaf in Ramallah, Bassam Shakaa in Nablus, or Tawfiq Ziad in Nazareth – often helped open these exhibitions.

In 1979, led in this effort by Isam Badr, they opened their first gallery in Ramallah. It was called Gallery 79 and the exhibitions soon became popular, attracting travelers from other areas. Out of the 15 planned exhibits, eight ran before the gallery itself was fully shut down. Mansour’s first solo show itself, in the Fall of 1980, lasted only four hours.

The crackdown on art was prevalent throughout the 1970s, as Israeli officials “would come and confiscate paintings that they didn't like,” Mansour said, noting they would even take things as simple as a woman wearing traditional embroidery and working in the field.

Over this time in the late 70s and early 80s, Mansour was jailed several times. Speaking of his own experience, he said about one interrogation:

“They didn’t tell me that I was arrested because I was an artist, but I think they wanted to intimidate me. They put a bag on my head; I was handcuffed behind my back; I was beaten, the same as what everyone else who is imprisoned goes through. I didn’t pose any threat in terms of security — they just didn’t like what we were doing.”

Nonetheless, Palestinian artists kept their fight going.

In the village, 1981

The Daughter of Jerusalem, 1978

Al-Quds - Jerusalem, 1983

Motherhood, 1980

In 1981, Mansour and other artists were told by Israeli head officers that every piece of art would have to be given a stamp of approval or not, and if it didn’t meet standards than it would be confiscated.

The targeting of art and symbols only heightened. Just the basic colors of the Palestinian flag – red, white, green, and black – were banned at this time. So not even the flag itself, also deemed illegal, but just the colors alone.

When Israeli officers gave Mansour and other artists these guidelines, fellow artist Issam Badr asked about painting a flower in those colors. Badr was told it would be confiscated. The officer then added “Even if you do a watermelon, it will be confiscated.”

The suppression, confiscation, and targeting of any content only made it stronger. "Anything that made Israel angry later became a symbol.”

The watermelon itself, for example, became a symbol of resistance at the time, and has remained used to this day. Other symbols of identity were also placed in the artworks to evade Israeli detection and reach the people.

In a February 2024 interview with Al Jazeera, Mansour said:

“They wanted to fight the notion of a Palestinian identity. Because our existence here, for them, is ‘antisemitic’. That we exist, only. It’s not what we do — just our existence here is something that they hate.

It does not fit their narrative about Israel. What are these people doing here? We came to a land that should be empty. So our existence here is something that makes them angry.

Existence as workers — that we work for them in the fields or in factories and so on — that’s okay. But existence, existence as a national identity, as Palestinians — that’s what makes them mad.”

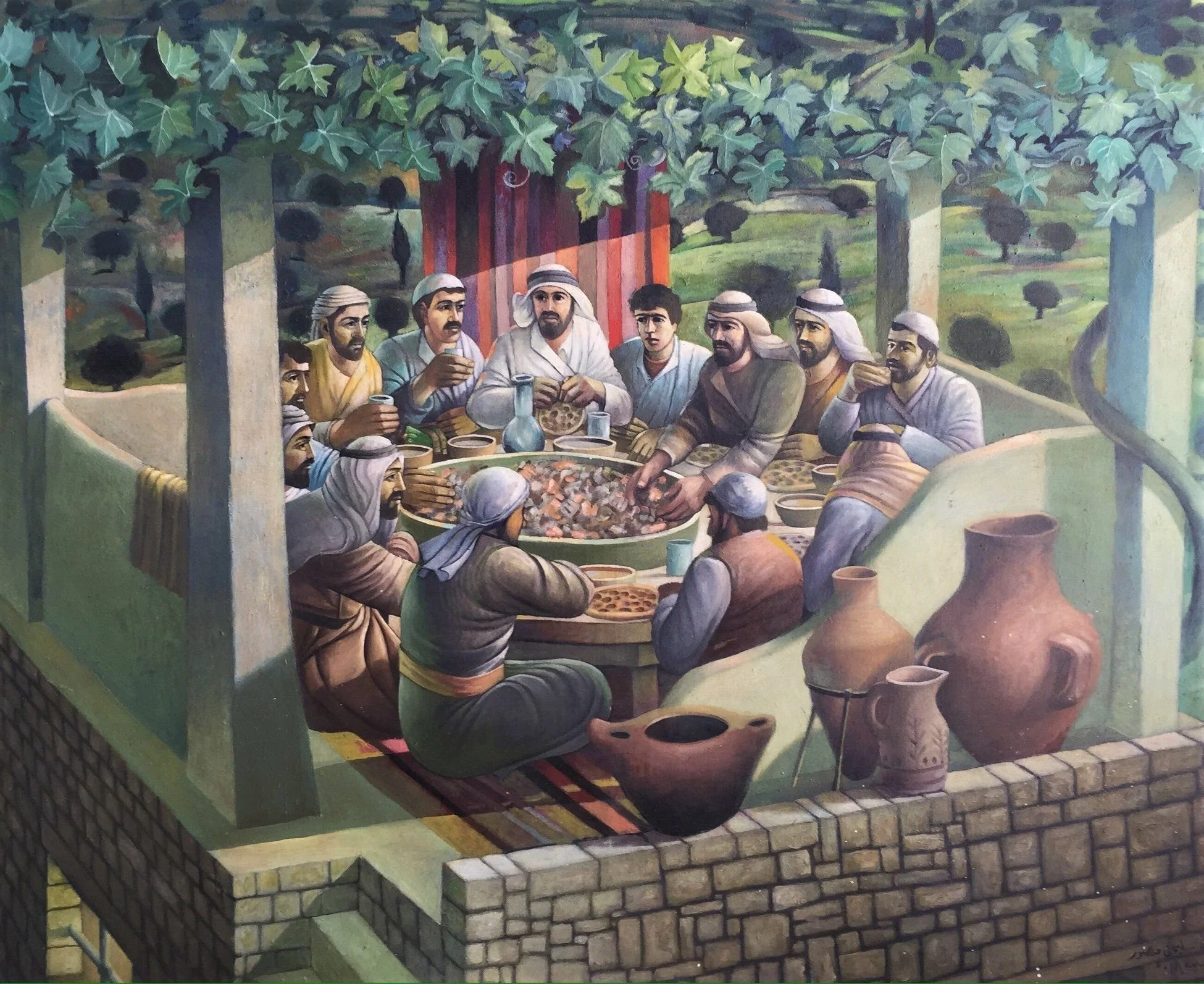

The Last Supper, 1994

Embrace, 2003

Olive grove, 2012

Motherhood, 2014

In 1987, Mansour co-founded the New Visions movement with fellow artists Vera Tamari, Tayseer Barakat, and Nabil Anani.

As Mansour’s official bio notes, “The movement was formed in response to the First intifada (started in 1987, ended in 1993) and called on artists to boycott Israeli art supplies and instead utilize local natural materials such as coffee, henna, and clay.

“Back then, most people were trying to (boycott Israeli goods and be self-sufficient), by farming their own piece of land,” Mansour said. “As an artist I thought, why don't we do the same? Why don't we search for natural materials to use in our work?”

Intifada, 1989

Mud was his primary tool of choice drawing from childhood memories of using it with his grandmother at a young age.

After initially trying to hide the cracks of the mud that appeared as it dried, Mansour started to realize the beauty in the cracks. “They reflected our political life here — the hundreds of checkpoints that fragment our landscape,” he said.

Reflecting on this time in a 2021 interview with Caravan, Mansour said about this time and artist-wide transition of natural materials:

“These artistic experiments helped to change and develop Palestinian art, and it formed a link between traditional art (art done between 1950-1988) and the new contemporary art, which started to be created by young artists at the beginning of the 21st century.”

The Pigeon’s Tower, 1987

Resting Woman, 1985

The Village Awakens, 1987

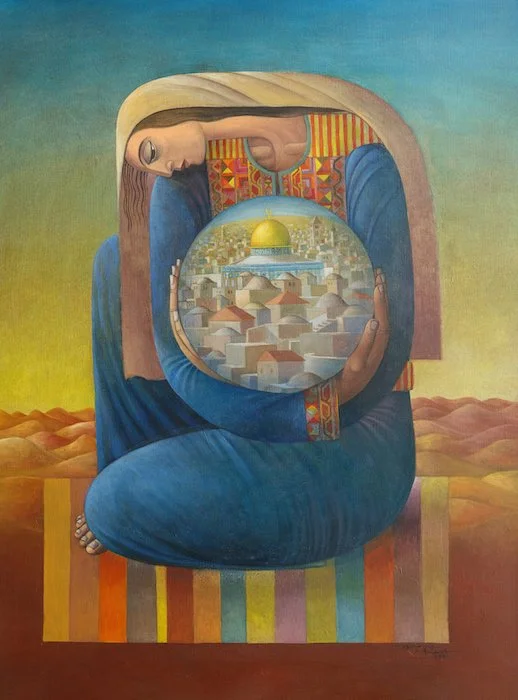

Woman Carrying Jerusalem, 1997

Loss, 2007

My name is Palestine and I will survive, 2016

Once the First intifada ended with the 1993 Oslo Accords, things shifted – but in a strange way. “After 1993, the fact that we are under occupation became blurred. Before that, it was very clear that we are occupied and there is an occupier,” said Mansour.

As the Oslo process was underway in the 1990s, Mansour’s involvement in art continued in other ways. He co-founded the Al Wasiti Art Center in East Jerusalem, which “was established to build a bridge between Palestinian artists and their compatriots in exile and other international artists to archive and preserve art in Palestine.” He served as its director from 1994 until 2003.

In her book, Samia Halaby notes about the center. (Again: Halaby refers to the League of Palestinian Artists as the Rabita)

“Mansour led the Rabita for many years during the 80's when it expanded dramatically and opened branches in Ghazze, Al Khalil, Al Bireh, and Ramallah. It was then that Mansour began thinking of a permanent gallery space for the Rabita.

The idea grew until it became the Wasiti Art Center, which opened in Al Quds in 1992. A restored Al Qudsi home with the mountain architecture of Palestine, houses the center.

Productive discussion among artists takes place at openings of Al Wasiti. Palestinians holding European or American passports and visiting from exile often attended, to keep in touch. Artists Tayseer Barakat and Vera Tamari founded the Wasiti with Mansour.

Through his position as director of the Wasiti, Mansour became a central connection to the world of Palestinian visual art.

In 1998, Mansour was also asked by the Minister of Higher Education to conduct a study on education in Palestine.

When Mansour gave a report back, he pointed out how no art school had been founded before the Oslo Accords. It was only after that universities just began having art schools.

Mansour was told there had actually been ongoing efforts by Palestinians to try to establish art schools prior, but they were always rejected by Israel. In addition to art schools, agriculture schools were also prohibited.

By the end of the decade, as with many Palestinians, Mansour did not see real change from the Oslo process. “Still (in the 90s), they didn’t accept us as normal people, They accepted us as half-human beings, with no rights at all.”

Martyrs (with mud), 1999

Picking Grapes, 1984

Jerusalem from the mount of olives, 1973

Gaza, 2012

Mother and daughter, 1983

In the village, 1981

Mansour eventually returned to the canvas and medium of painting, but he continued to work with mud as one of his tools.

Sometimes he even mixes mediums within a singular piece, as shown in the examples below.

Portrait of a man, 2017

Portrait of a woman, 2019

Over the years, he’s continued to make work and found a new generation to engage with his work on Instagram. He continues to be active making work.

Today, Mansour lives in Al Quds / Jerusalem. His art studio is in Ramallah in the occupied West Bank, forcing him to make the journey across Israeli checkpoints almost daily. The length of the journey? Sometimes as short as 45 minutes. Sometimes as long as six hours.

If it was up to Mansour, he would live by his studio and not have to make this commute. However, he needs to continue living in Jerusalem in order to keep his ID – which allows permanent residency to those who were born in Jerusalem or already lived there before 1967. It doesn’t mean you’re an Israeli “citizen” but you are able to travel to Israel and go abroad with it. The stipulation is you have to keep living there.

“You always have the feeling you are breaking some law, but you don't know what you are doing wrong. You constantly feel threatened. You are not free,” Mansour said. “I don't like Jerusalem, anyway. It's a place for tourists. If you go to the Old City, everything is just souvenirs or restaurants. It's not vital like it used to be. If I could choose, I would rather live in Ramallah or Birzeit.”

Woman in orange orchard, 2015

Early in the morning, 1979

Orange pickers, 2013

Jerusalem, 2023

Shrinking object (Mud on wood), 1996

Childhood home, 2016

Father and mother on their wedding day, 1984

In the midst of the ongoing Gaza genocide, Mansour has lost friends such as fellow artist Fathi Ghaben.

In an interview with the National News in December 2023, he said:

“All the images that come to my mind are really horrible. Some I can't get out of my mind – I can only get them out through painting. You know, I always hated abstract expressionism. I didn't like it. But I think now is the time for it.”

Mansour’s process has also changed to be more immediate and direct, not making any sketches ahead of time but instead starting right on the canvas with color paint.

“There’s a different kind of artistic solution for everything and it reflects the problem you are dealing with,” he said.

Later, in an October 2024 interview with Savior Flair, he said:

“Many artists, myself included, are unsure of what to do at this moment. I can say this is the most challenging period I’ve ever experienced. As an artist living under occupation, not knowing what to do is incredibly difficult. Our work and production have significantly decreased, but for now, we continue to try, hoping that change will come through persistence.”

Mansour also had a stroke a couple of years ago, which has made painting take more time to focus on and do. But he’s still pushing forward and tries to keep his routine of continuing to work every day. He also has dedicated his recent time to mentoring young artists and students.

Mansour’s art ties to the concept of sumud. He told Al Jazeera:

“The meaning of it in English is steadfastness. For me, sumud is to not forget who we are and to fight all the time for our liberation. Not to give in to the demands of Israel — that if we want to live in this land, we have to live like a second-class people.

That is mainly what Israel wants of us — to accept that they are the rulers of this land. Sumud, for me, means that I don’t agree with that. And I will fight that.”

Rituals Under Occupation, 1989

Revolution was the Beginning, 2016