Part 5 -

Palestinian Art History

Second Intifada

2000 - 2005

After the “peace process” of Oslo proved to be a failure, another rebellion began.

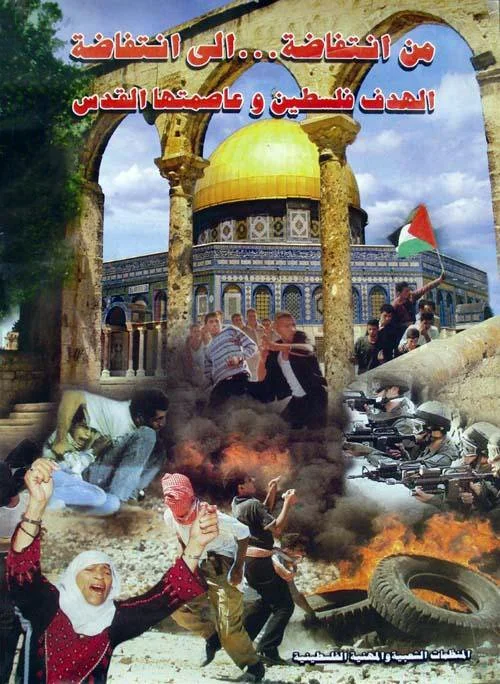

From Intifada...To Intifada

Poster by Abd Almouty Abozaid, 2001

via Palestine Poster Project

Bursting The Bubble

In what were supposed to be the transition years of Oslo from 1993-2000, things had only gotten worse.

The Palestinian Authority (PA) put in place had proven to be not just incompetent, but ultimately seen as corrupted collaborators in implementing the same system of Zionist oppression. In the West Bank, the amount of settlers doubled from 200,000 to 400,000 in this period.

By the time the Camp David Summit in the United States wrapped up in the summer of 2000, a last ditch effort with no resolution for Palestinians, there was no lack of clarity in where things stood.

Any initial optimism for the Oslo Accords had vanished, those like Edward Said who predicted its shortcomings were proven correct, and the momentum from the first Intifada had been weakened by the agreement.

How Will Ariel Ever Get This Clean?

by Kado Advertising Agency, 2002

via Palestine Poster Project

A couple of months later, things would take another turn when Ariel Sharon paid a visit to Al-Aqsa Mosque. Sharon served as a longtime IOF military leader – dating back to being a platoon commander in the 1948 Nakba and being involved in many of the major attacks until his transition to politics with involvement in the Israeli Likud party in the 1970s. When the party held government power during the invasion of Lebanon in 1982, Sharon was deemed personally responsible for the Sabra and Shatila massacre of Palestinian refugees. In 1999, he had become the leader of the Likud party.

On September 28, 2000, Sharon stormed Al-Aqsa Mosque with more than 1,000 armed Israeli officers, a blatant show of disrespect for Palestinians and Muslims alike as the ultimate holy location of the land.

Immediately after, Palestinians began to protest. They were immediately met with violence by Israeli officers. From some civil disobedience and stone-throwing by Palestinians to the IOF using rubber bullets and live ammunition.

On September 30, only a couple days into protests, 12-year-old Muhammad al-Durrah was martyred by Israeli military fire at the Netzarim junction during the midst of protests in Gaza. He was hiding behind his father, Jamal al-Durrah, who survived. Captured by Palestinian cameraman Talal Abu Rahma, the scene has remained embedded in the minds of many.

12-year-old Muhammad al-Durrah and his father, Jamal

Gaza strip on September 30, 2000 at the start of the Second Intifada

Captured by cameraman Talal Abu Rahma for France 2 TV

Mural of Muhammad al-Durrah

Artist and year unknown

The Israeli army and government would, for years, try to push lies about the footage. But it was a window into the world of the violence that foreshadowed the upcoming IOF aggression.

Within the first week, there were dozens of martyrs and almost two thousand injured. A majority of those attacked were just civilian bystanders, not even part of the demonstrations. Over the first month, over a million rounds of Israeli ammunition were reportedly fired.

This proved to be a landmark point, and the Second Intifada was born – also known as the Al-Aqsa Intifada.

Intifada 2000

Painting by Ismail Shammout, 2000

via Dalloul Art Foundation

Only a few months earlier (in May), Hezbollah forces in neighboring Lebanon had achieved a victory in getting the Israeli Occupation Forces to evacuate out of southern Lebanon, ending what had formally been 15 straight years of occupation there. Hezbollah, which had been born out of Israel invading the southern part of their country, had demonstrated another example of the power – and necessity – of armed resistance against occupiers.

With this new uprising, Palestinians under attack and ongoing occupation were hardly left with an alternative to armed struggle continuing to play a central role. Certainly this was the perspective of the coalition of Palestinian groups who had rejected the Oslo process from the very beginning – including Hamas, Islamic Jihad, and the PFLP. There were only some like Mahmoud Abbas who felt that military confrontation would only result in an Israeli victory, and repeatedly tried to propose a reduction of military operations. They were in the minority. Within Fatah, the Tanzim group led by Marwan Barghouti felt that more negotiations would just be a pretext for more annexation.

This time, however, the heightened intensity of Israeli crackdown meant that popular protests among civilians was not possible in the way it had before. As noted in The Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question:

“The intifada had already shifted in late November 2000 from mass demonstrations to shooting attacks by Palestinian activists (mainly by Fatah in the first stage) as a response to Israel's harsh repression, and levels of violence varied during the following months.

Israeli actions took the form of shelling PA administrative offices and security compounds, conducting incursions in areas under PA's jurisdiction, closing off these areas, imposing curfews, carrying out targeted assassinations of militants, leveling houses, uprooting agricultural lands, and erecting hundreds of checkpoints to hinder Palestinians' movement.

Palestinian militants resorted to detonating road-side bombs, firing at Israeli soldiers and settlers, launching mortar attacks (mainly against Israeli military positions and settlements in and around the Gaza Strip), and, starting late May 2001, carrying out suicide bombings (principally by Hamas, followed by Fatah and Islamic Jihad).”

The suicide bombings were “weapons of the last resort” according to Abdel al-Aziz Rantisi, a Co-Founder of Hamas (then assassinated in 2004), and this method was primarily just implemented for a stretch during this period.

A 2000 poster about Faris Odeh, a 13-year-old who was martyred 10 days after this photo of him throwing a rock against a military tank

via Palestine Poster Project

“The Palestinians did try to conduct the Aqsa Intifada along the lines of the former intifada. But the Israeli army left them no choice but to react to the much deadlier and superior Israeli violence,” wrote Ilan Pappé, a well-known historian who lived in Israeli-designated territory.

Pappé also added that former Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak “offered the Palestinians a take-it or leave-it deal at Camp David. The Palestinians didn’t take it, and the Israeli response was: If you don’t accept our offer, you are going to get crushed and severely punished.”

Ariel Sharon, who had lit the spark was for the Al-Aqsa Intifada, succeeded Barak as Israeli Prime Minister in February 2001. This only solidified the uprising, which would spread beyond just the West Bank.

During this time – to try to further restrict movement for Palestinians – there were hundreds of Israeli roadblocks, closures, and an overall blocking of travel between villages, camps, and cities. Even in emergency situations, such as pregnant women needing to reach hospitals, it did not matter.

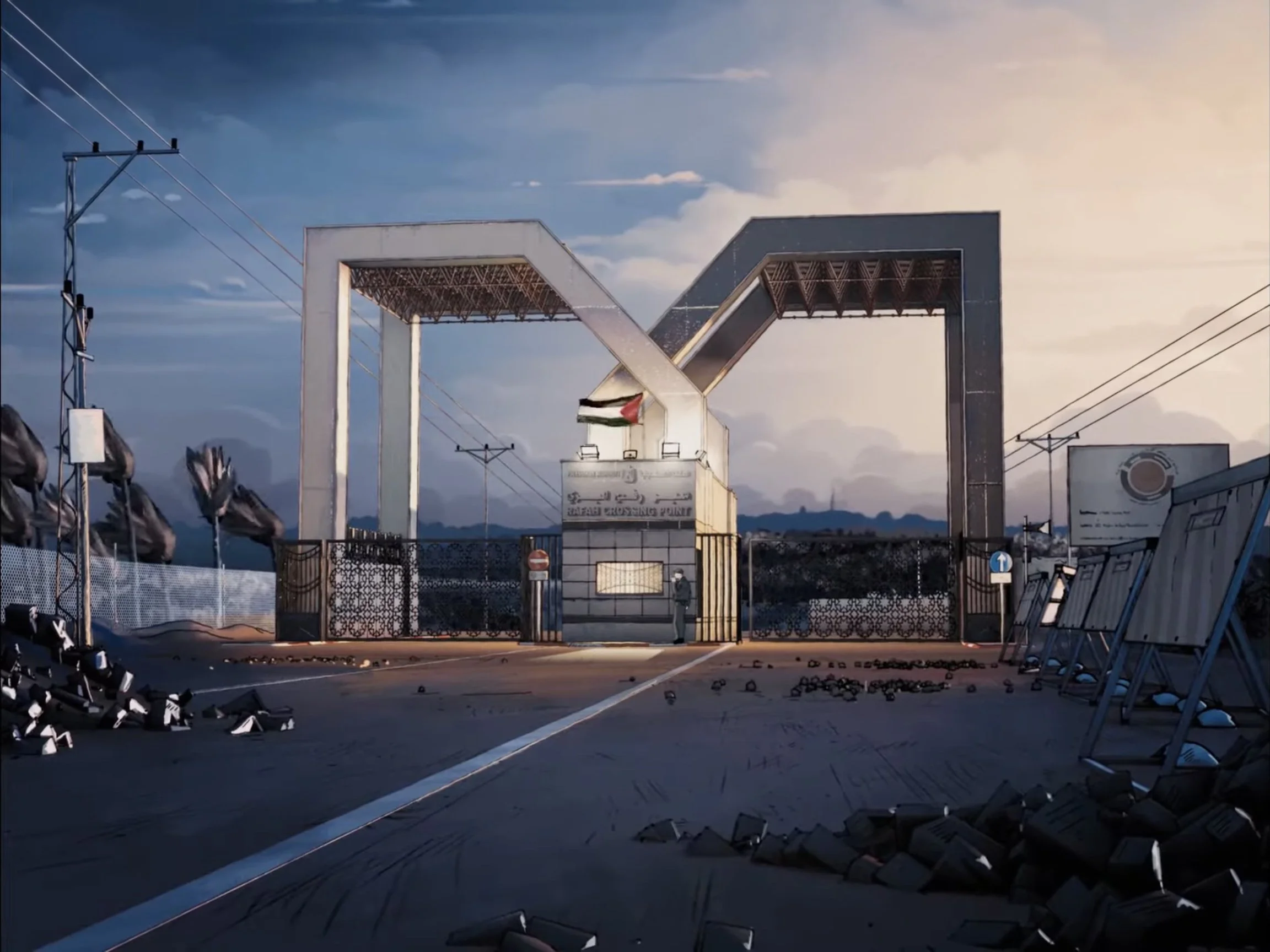

This included the destruction of the Gaza International Airport, which had just opened in 1998. It was seen by some as a step towards future independence, though Israeli security was in complete control of who flew, as well as managing security checks at the airport. As soon as the Second Intifada kicked off, flights from Gaza were halted on October 7, 2000. Starting in 2001, Israeli planes targeted the airport with airstrikes and their tanks tore up the runway.

Gaza International Airport in a postcard for Palestinian Airlines, sometime after the airport opened in 1998

In March 2002, Israeli Occupation Forces decided to invade Area A of the West Bank. They brought in snipers, attack helicopters, armored bulldozers, and tanks – resulting in over 500 Palestinian martyrs during the two months of attacks. This included the 10-day battle in the Jenin refugee camp. After a month of sustained attacks, forces removed some troops while continuing to launch attacks.

Right after this, in June 2002, the Israeli government approved the initial construction of the Apartheid Wall, aka the Separation Wall, annexing more land to Israeli control – which was later determined by the International Court of Justice to be violating international law.

View of the Dome of the Rock at Al-Aqsa Mosque, within Al Quds, past the Apartheid Wall

Photo by Ryan Rodrick Beiler

While the West Bank was the focus in the first years of the Second Intifada, the Gaza strip became a more focal point later. The Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question notes:

“By 2003, the main battlefield had shifted to Gaza, with skillful camp-based resistance, an extended territorialized version of the Jenin strategy. Israeli settlements were regularly blockaded by Palestinian fighters and presumed to be surrounded by treacherous deadly explosive devices hidden in the sands: Israeli tanks and armored personnel carriers were blown up. Israel assassinated Palestinian leaders, particularly those of Hamas, which resulted in deadly revenge attacks, in turn occasioning Israeli airborne reprisals, causing heavy civilian deaths and injuries.”

The Eyes of Cinema

In the Spring of 2002 immediately after the Battle of Jenin, director Mohammad Bakri snuck into the closed-off Jenin refugee camp with a camera and sound person. They filmed interviews with the Palestinians of the camp, who shared their experiences about the Israeli Occupation Forces attacks.

Bakri had been living in the ‘48 territories – where he was technically an “Israeli citizen” though he was not treated equally because of his Palestinian background. Bakri was tired of only seeing the “Israeli” side being covered. He wanted to give his people a voice. This became the documentary of Jenin, Jenin (2002).

Jenin, Jenin (2002)

Directed by Mohammad Bakri

Jenin, Jenin (2002)

Directed by Mohammad Bakri

After premiering in October 2002, the film quickly drew the fury of the Israeli army, government and public, receiving a ban until later in 2003. It would go into a relentless legal battle in the coming years, particularly with legal action pursued by IOF soldiers who felt their actions in the film “portrays us as war criminals and murderers, as the perpetrators of a massacre, and effectively, without explicitly saying so, as Nazis.”

This is not an assertion that Bakri himself makes in the film. It’s viewed a documentary for capturing moments of real life, but it does not have a narrator who explains everything that happened, nor does it try to be a definitive record. Rather, it just embraces his mission to give Palestinians an outlet after the Battle of Jenin.

While in modern day everyone has a phone camera where images and videos can be easily shared across social media channels, that was not the case yet at this time. Jenin, Jenin gave Palestinians a chance to share their side and describe in their own words how they’d been affected.

Jenin, Jenin (2002)

Directed by Mohammad Bakri

Jenin, Jenin (2002)

Directed by Mohammad Bakri

Separately, an up-and-coming filmmaker in the diaspora at this time was Rosalind Nashashibi, who was was born in London to a Palestinian father and Irish mother but often took trips back at a young age to visit family in the West Bank.

During the early 2000s, Nashashibi started to make short films in Palestine – Dahiet al Bareed, District of the Post Office (2002) and Hreash House (2004). Those two shorts showed her early interest in ways to capture her family homeland, and each had a personal connection. Dahiet al Bareed was where her father grew up. More notably, the town was actually conceived and built by her grandfather, who had ran the Palestinian Post Office.

The neighborhood itself eventually floated into a grey area of sorts. “It is technically West Bank but it has never been under the control of the Palestinian Authority — it’s under the administrative division of the Israeli military,” Nashashibi said of the featured area “Nobody was really looking after the place so the kids seemed to be ruling the streets. A place defined by the checkpoint down the road and its position as neither Occupied Territory nor the West Bank.” She ended up making the self-titled Dahiet Al Bareed, District of the Post Office (2002) and simply documented some moments of everyday life.

Dahiet al Bareed, District of the Post Office (2002)

Directed by Rosalind Nashashibi

Dahiet al Bareed, District of the Post Office (2002)

Directed by Rosalind Nashashibi

Dahiet al Bareed, District of the Post Office (2002)

Directed by Rosalind Nashashibi

Dahiet al Bareed, District of the Post Office (2002)

Directed by Rosalind Nashashibi

Nashashibi’s next Palestine-based short film, Hreash House (2004), was inspired by visiting a family friend in Al-Nasirah – aka Nazareth – where she wanted to capture the collective living and community inside this one home. It ended up being filmed over four weeks, including a big dinner during Ramadan.

''My father grew up in that situation,'' Nashashibi said. ''My mother also grew up in an extended family in Belfast, and she talked about it a lot, what she had that we didn't have: big family dinners that went on for ages, big discussions around the table. I didn't have that when I grew up. Most of the world is still structured like that, although it is changing; the extended family has a much larger significance than just Palestinians or Arabs.''

Hreash House (2004)

Directed by Rosalind Nashashibi

Hreash House (2004)

Directed by Rosalind Nashashibi

Hreash House (2004)

Directed by Rosalind Nashashibi

Hreash House (2004)

Directed by Rosalind Nashashibi

Shrinking object (شئ متقلص)

Mud on wood

by Sliman Mansour

via artist archive

Art Veterans Transition to New Century

As the Second Intifada began at the end of 2000, established Palestinian artists from the prior decades and half-century continued to make important work, many opening themselves up to continual experimentation.

Artists like Sliman Mansour had, since the First Intifada, began to experiment with new mediums or techniques. Mansour continued to do that into the 2000s, working with mud in what would become a permanent tool in his creative kit.

The experimentation was not exclusive to those part of the New Visions group, of course. Samia Halaby, for example, was in New York City and had become interested in the Amiga computer – exploring the creation of digital, animated paintings. Both Mansour and Halaby continued to also make work in their more traditional painting style at this time of the century change as well.

Vera Tamari went even further outside of her previous comfort zone. She had been part of the League of Palestinian Artists and a member of the New Visions group during the First Intifada, as well as a founding member of Al-Wasiti Art Center. Along with her brother, Vladimir Tamari, their family had cemented themselves as part of the Palestinian art world.

During the Second Intifada, in 2002, Tamari took her work outside the traditional scope by creating a special installation – entitled Going for a Ride? – her most notable and discussed creation of this period.

In the installation, she took a group of cars and lined them up in an intentionally-designed way at a field by her house as a commentary on the continual destruction of the cars (and other property) by Israeli Occupation Forces.

One of the cars from the Going For A Ride? installation

by Vera Tamari, 2002

However, it was upon the art opening that it really took on its final form. After the launch festivities, with a celebration that lasted late into the night, Tamari then woke up at 4am to loud noises. What she saw, and captured on video, was Israeli tanks who eventually decided to run over the whole exhibit repeatedly before shelling and urinating on the wreckage. Tamari felt this realized her concept better than she could have even imagined – the “ultimate metamorphosis” for the piece. For example, before she had tried to make the illusion of tank tracks in the dirt, but now she had real ones as the Israeli forces proved her point.

Tamari’s usage of “found” objects was one of several installations during this time, particularly in Ramallah, as artists continued to expand their imagination – both as a means of necessity and survival, as well as just finding new ways to communicate their ideas.

Other established artists such as Ismail Shammout and Tamam Al-Akhal, who had come from a generation prior, stuck more to what they knew at an older age. That is not to say it in a negative light, as in fact they were arguably at the top of their game. The end of the ‘90s into the early 2000s was a key time as they finished and exhibited their series – Palestine: The Exodus and the Odyssey. Both also continued to make paintings. Shammout created until passing away in 2006 from his ongoing health issues, leaving behind an important legacy.

The Dreams of Tomorrow

Painting by Ismail Shammout, 2000

via Funun Arts archive

We Are The Wall

Painting by Ismail Shammout, 2004

via artist archive

Untitled orange tree painting

by Tamal Al-Akhal between 2000-2010

via artist archive

Developing & Showcasing Creativity

After there were finally a group of art spaces established in the 1990s, particularly in the West Bank, they continued to play a role in cultural development.

This wasn’t without difficulties during the Second Intifada, when several of these institutions were shelled and ransacked by Israeli forces. The Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center was one of these places impacted, but they continued to do important work during this period.

Often the center featured solo exhibitions of many different Palestinian, Arab, and other artists across mediums – such as Samir Salameh, Rudanya Qasrawi, Dina Ghazal, Husni Radwan, Mohammad Saleh Khalil, Rashid Koraichi, and many more.

Earth and Sky exhibit of art by Rudanya Qasrawi

at Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center

via Palestinian Museum Digital Archive

Earth and Sky exhibit of art by Rudanya Qasrawi

at Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center

via Palestinian Museum Digital Archive

Earth and Sky exhibit of art by Rudanya Qasrawi

at Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center

via Palestinian Museum Digital Archive

This also included an exhibit in February 2001 where Adila Laïdi-Hanieh, Director of Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center at the time, wanted to put together an exhibit that honored the martyrs, give families a place to grieve, but also a place where they could get to know who these people were. This became a show entitled 100 Shaheed, 100 Lives where everyday objects important to each civilian victim were brought in to represent them, along with a personal photograph.

From the "One Hundred Shaheeds - One Hundred Lives" exhibit in 2001

Section of the Khalil Sakakini Cultural Centre Brochure

via Palestinian Museum Digital Archive

“The objects included a woman's unfinished piece of embroidery, a favorite cup from which a young man used to drink his morning coffee, a candle holder a youth had brought back as a souvenir from Egypt, a schoolboy's tie and jacket, a wedding photograph, jeans, headphones, a key chain, worry beads, an amulet, a schoolbag, a t-shirt, a cap, a pen,” wrote Kamal Boullata in his book Palestinian Art.

The Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center also contributed to fostering creativity in even younger kids by hosting art workshops after the end of normal public school hours. In addition, they created booklets after featuring images of the students work, their names, and the names of their schools.

"Children Are Drawing" brochure by the Khalil Sakakini Center

Early 2000s

via Palestinian Museum Digital Archive

"Children Are Drawing" brochure by the Khalil Sakakini Center

Early 2000s

via Palestinian Museum Digital Archive

Another institution that was making an impact with a younger generation was A.M. Qattan Foundation, which started the Young Artist of the Year Award (YAYA) as an ongoing biennial program in 2000.

They were focused on artists slightly older than just students, as it was open to artists in their twenties. The only requirement was to have at least one Palestinian parent, but you could be living anywhere in the country or diaspora.

The idea was for group of around a dozen finalists to be selected and then a jury of both local and international artists would evaluate the work. It was a program designed most importantly to nurture the developing artists.

1st prize in the 2000 Young Artist of the Year Award (YAYA) by A.M. Qattan Foundation

Parts of A Wreath by Raeda Saadeh

via A.M. Qattan Foundation archive

1st prize in the 2000 Young Artist of the Year Award (YAYA) by A.M. Qattan Foundation

Parts of A Wreath by Raeda Saadeh

via A.M. Qattan Foundation archive

Mediums included drawings, paintings, film, photography, video, installations, and more. This included a mix of Palestinian artists from across the country and sometimes from the diaspora. From the start, even just being chosen as a finalist led to more attention on an artist’s work and several were then invited to exhibit abroad.

1st prize in the 2002 Young Artist of the Year Award (YAYA) by A.M. Qattan Foundation

Kite by Iman Abu Hmid

via A.M. Qattan Foundation archive

During the 2002 exhibition, it was observed that artists did not desire to reflect the ongoing violence or make traditionally nationalistic paintings – though several still made work through the lens of their Palestinian identity and reality. Each artist focused on their own personal perspectives.

Kamal Boullata, who himself was part of the jury at one point, writes in Palestinian Art:

“To the young artists who participated in the 2002 Biennial Exhibition, and those who attended the workshops, the very act of creating a work of art was experienced as an expression of defiance and an assertion of the will to resist the bleak reality of everyday life in the ghetto where indiscriminate violence continued to be waged against their besieged people.

As to the audience that was able to view the exhibitions, the artists' works declared that no one stands alone, be they artists or viewers. Through the wide range of art works created by the youngest generation of Palestinian artists, a whole new horizon seemed to loom beyond the walls being raised around them.”

End of Second Intifada

Mahmoud Abbas had been a longtime Fatah member, recruited in 1961 soon after Arafat co-founded it, and was the PLO signatory for the Oslo Accords.

Yassir Arafat was serving as President of the Palestinian Authority (PA) during the Second Intifada, and in 2003 he faced U.S. and international pressure for a shift in leadership to try to work out a deal. He had strategic differences with Abbas, but reluctantly agreed to appoint him to a Palestinian Prime Minister position. However, Abbas attempts at peace talks bore no results and he resigned later that year with no success. He and Arafat struggled over their political perspectives and power distribution. Arafat passed away from health issues in late 2004 and it was Abass who took over as the PLO Chairman.

Elections for the Palestinian Authority were soon held at the start of 2005 to officially determine Arafat’s successor.

Section from a 2005 poster about women’s role in voting in the ‘05 elections

Women's Affairs Technical Committee by artist unknown

via Palestine Poster Project

However, it was an election that was boycotted by Hamas and Islamic Jihad, with few other known candidates able to compete. Abass then became the PA President with the Fatah party.

He had been against Palestinian militant operations from the beginning. After being elected, Abass was able to come to an agreement with the leadership of Hamas and other Palestinian factions to stop military operations until the end of 2005. Afterwards, legislative elections would be held. This allowed for Abass to then sign a ceasefire agreement with Ariel Sharon at the Sharm El Sheikh Summit in February 2005.

The deal included the "redeployment" of the Israeli forces from Gaza to the borders, a plan that had been devised by Sharon in the previous years, where Israeli forces controlled the Gaza strip in a new way. The terms also included the retreatment of four settlements in the northern West Bank. The Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question notes:

“The disengagement (carried out in August–September 2005), combined with the construction of the separation barrier in the West Bank, marked an important step in Israel's strategy to separate the Gaza Strip from the West Bank and to consolidate its control over the West Bank.”

The agreement formally marked the end of the Second Intifada / Al-Aqsa Intifada. There were around 5,000 Palestinian martyrs reported from this time, a quarter being children. In addition, a higher number of other Palestinians were injured.

After the agreement, IOF troops evacuated the Gaza Strip and over 9,000 Israeli settlers living in 25 settlements across the area were evicted. By the end of September 2005, their had been a complete withdrawal from Gaza. This was a notable victory in the moment, as the first Palestinian land to be secured again.

Construction on the Aparthied Wall in the West Bank, 2006

Photo by John Tordai

via UNRWA archive

Shifting Strategy

2005 - 2010

After the Second Intifada, both the political and artistic ways of life would be altered.

Hamas Gains Control of Gaza

Legislative elections were held in January 2006 for the second Palestinian Legislative Council (PLC), the legislature of the Palestinian National Authority (PNA). Hamas won both a majority of the vote and a majority of seats in the assembly.

After Fatah and leader Mahmoud Abbas were defeated in this election, they did not acknowledge the results. The internal conflict between them came to a head in June 2007, when Hamas expelled Fatah out of Gaza and took over full control there.

The West Bank was now split off, politically and administratively, from the Gaza Strip. The separation more generally had been a long time coming, as an electronic fence and concrete wall around the Gaza had already been implemented by Israel in 1995, as part of longtime restrictions on the territory.

In reacting to Hamas’ 2007 control of Gaza, Israel reacted by implementing a full-on land, air, and sea blockade. (Egypt also contributed to keeping the borders shut through the southern Gaza crossings.)

As Al Jazeera notes, “Israel claims that its occupation of Gaza ceased since it pulled its troops and settlers from the territory, but international law views Gaza as occupied territory since Israel has full control over the space.”

A Palestinian flag flying in Gaza

by unknown photographer

In the West Bank, Israeli settlements continued to be built on Palestinian-designated territory and the Apartheid Wall continued to be constructed, annexing more land away as well.

Humor & Absurdity

While the initial time after the Second Intifada is not as clearly defined artistically, there are a couple of themes that can be pointed out.

Sascha Manya Crasnow, Lecturer of Islamic Arts, wrote in her 2018 dissertation, The Next Generation, that there had been a shift that started with the turn of the century:

“With the signing of the Oslo Accords.. poster production declined due to the breakup of a unified politicized art department in lieu of NGO-funded local projects and the advent of the internet supplanting poster dissemination as the most cost-effective option for circulating information and imagery.

By the outbreak of the Second Intifada, the disillusionment with the Accords had set in, and artists began to take on new approaches in their artistic expressions — ones which appropriately articulated their frustration at the inter-Intifada period and the quotidian realities with which the failure of Oslo had left them.”

Crasnow pointed out recurring themes like absurdity, humor, and time. (A focus of humor and absurdity is also recognized in The Origins of Palestinian Art book and the contemporary art reflection website page from The Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question.)

Humor in this period, Crasnow argues, served as a tool to highlight and critique the cyclical realities they were forced to endure – particularly with the failure of the Oslo peace process and the empty promises it presented.

This seemingly started to become more heightened once the Second Intifada had formally ended in 2005. One artist who made a piece engaged with this concept was Raeda Saadeh in her 2007 short film,Vacuum.

Frame from Vacuum (2007)

by Raeda Saadeh

In it, Saadeh herself is shown vacuuming as a representation of Palestinian women within the ongoing occupation and their long history to the land. Crasnow notes:

“Recorded in the Palestinian desert between Jericho and the Dead Sea, Saadeh’s two-channel 17-minute video depicts the artist dressed in a simple black abaya vacuuming the seemingly endless desert. The audio contains the actual sound of her vacuuming as Saadeh connected the device to a generator with over 1,000 feet of cable to allow her to actually engage in the act of vacuuming the desert, rather than simply mimicking the absurdist action.”

Saadeh had been the first ever winner of the Young Artist of the Year Award (YAYA) by A.M. Qattan Foundation, held in 2000, and Vacuum continued the evolution of her work.

At the Sharjah Art Foundation where this was exhibited in 2007, they also note:

“In displacing a mundane domestic task and performing it in an absurd context, Saadeh emphasizes the inanity of our tendency to preoccupy ourselves with tedious, repetitive tasks that distract from deep-seated issues which are not as easy to ‘clean up’.

Aside from engaging with the personal sphere, the nonsensical and impossible task of vacuuming the naked hill highlights the ineffectualness of attempts at tidying up political realms as well. The work, in a sense, confronts the popular Zionist slogan, ‘A land without a people for a people without a land’, demonstrating that, just as it is futile to try and ‘clean’ a mountain of all the dust and rocks that form the essence of its composition, it is infeasible to erase – completely – the memory of a people from its homeland.”

The theme of time can be seen in other artist’s work, such as artist Sharif Waked’s 2010 video, Beace Brocess.

Some artists in this period used humor to engage with foreign audiences in a new way outside of the traditional distribution of information about the Palestinian people. Waked, however, instead uses well-known imagery to make a point.

Beace Brocess (2010)

by Sharif Waked

The three-minute video of Beace Brocess loops footage from the Camp David Summit negotiations in 2000 between Palestine and Israel, featuring Yasser Arafat and the Israeli Prime Minister at the time. However, the figures are turned into black and blue silhouettes against a plain backdrop. It utilizes whimsical and generic royalty-free piano music in the audio, seemingly nodding back to the time of silent films and their absurdity.

In general, Crasnow notes how the use of humor was also perhaps implemented to fight back against the negative stereotypes of Arabs and Muslims – and increased Islamophobia – more broadly in a post-9/11 context.

“In addition to bypassing compassion fatigue, these humorous works present an alternative image of Palestinians—one of a people who are able to make jokes and laugh about their situation, rather than simply the dichotomous images of the aggressive keffiyah-clad ‘terrorist’ or helpless victim which are frequently depicted in international mass media.”

Divine Intervention (2002)

Directed by Elia Suleiman

Evolution of Cinema

After making his first feature-length narrative film in the 1990s, Palestinian director Elia Suleiman continued to make more in the 2000’s – with Divine Intervention (يد إلهية ) in 2002 and The Time That Remains (الزمن الباقي ) in 2009.

The trilogy of these features served an important role in Palestinian cinema, as noted in The Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question:

“The consensus among critics is that through these three films Suleiman brought about a qualitative leap in Arab filmmaking, in narrative technique and in cinematic style and language, a leap that made it possible to make out details of the Palestinian cause and follow its course, in a language that does not drift into the revolutionary rhetoric that Palestinian filmmaking had adopted in the 1970s.”

Divine Intervention (2002)

Directed by Elia Suleiman

The Time That Remains (2009)

Directed by Elia Suleiman

The NGO of Shashat, which translates to Screens, was set up in Ramallah in 2005 to help nurture the growth of Palestinian women in cinema – including training, mentoring, production support, and exhibitions. They also started The Women’s Film Festival.

One woman who made a big impact was Annemarie Jacir, who in 2007 became the first Palestinian female director to release a feature film: Salt of this Sea (ملح هذا البح).

The story is about a the daughter of Palestinian refugees who returns back to her homeland. It went on to win the International Critics award (FIPRESCI) at the Cannes Film Festival that year, in addition to other acclaim. However, she was banned from returning to Palestine after the film was made.

Salt of the Sea (2007)

Directed by Annemarie Jacir

Filmed in the West Bank, Salt of the Sea had 80 locations and was logistically complicated given the checkpoints, blockades, rejection of permits, and more obstacles. "In some cases we just filmed anyway. We put the actors in a real situation and we just did it guerrilla-style. That's how most Palestinian filmmakers are managing to do their work," Jacir told CNN in a 2009 article.

While Palestinian cinema was developing in a growing direction, it still faced many obstacles with the complications of everyday life and general Israeli military occupation.

On the viewer side, this also included a severe lack of movie theaters – with only one in the West Bank, and none in Gaza, at this point.

Al-Kasaba Theatre & Cinematheque in Ramallah, the only West Bank movie theater open at the time

Photo by Mel Brickman

via Palestinian Museum Digital Archive

Even the West Bank’s singular theater was attacked during the Second Intifada, but its recovery and maintenance still persisted afterwards.

Al-Kasaba Theatre & Cinematheque

Photo by Mel Brickman

via Palestinian Museum Digital Archive

Artist Support in Gaza

While many of the art organizations had been operating out of the West Bank, a similar system in Gaza had not yet been able to be setup.

However, two leading groups emerged in the early 2000s. One was Eltiqa Group for Contemporary Art, which was founded in 2002 by seven Palestinian artists. The intiative and gallery space put on workshops, offered exhibiton space, and helped with art education.

The other was Shababeek for Contemporary Art – or translated in English to Windows for Contemporary Art – which opened in 2009 as a nonprofit arts education center and gallery space. It was established in Gaza City, nearby Al Shifa Hospital. They sought out to give artist grants and host residencies, exhibitions, student initiatives, and more to help with public art programming in the Strip.

Culture Under Occupation

2010 - 2023

The arts and life in general tried to continue while Gaza remained under an air, land, and sea blockade – including amidst several attacks from Israeli Occupation Forces.

Picasso in Palestine

Another arts organization that had been founded in 2006 was The International Academy of Art Palestine (IAAP), the first institution dedicated exclusively to the study of visual art in Palestine, based out of Ramallah in the West Bank.

One of the co-founders of the The International Academy of Art Palestine (IAAP) was Palestinian artist Khaled Hourani, who was then General Director from 2010-2013.

His most well-known project is bringing a Picasso painting to be temporarily exhibited in Ramallah. The artist choice was less for his notoriety purely as an artist but as one who engaged in topics of politics, war, peace, and conflict. Picasso himself once said:

“What do you think an artist is? An imbecile who only has eyes, if he is a painter, or ears if he is a musician, or a lyre in every chamber of his heart if he is a poet, or even, if he is a boxer, just his muscles? Far from it: at the same time he is also a political being, constantly aware of the heartbreaking, passionate, or delightful things that happen in the world, shaping himself completely in their image. How could it be possible to feel no interest in other people, and with a cool indifference to detach yourself from the very life which they bring to you so abundantly? No, painting is not done to decorate apartments. It is an instrument of war.”

In 2011, Picasso’s “Buste de Femme” painting (worth $7.1 million at the time) was brought from the Van Abbemuseum in The Netherlands to Ramallah in Palestine. The specific piece was voted on by Hourani’s students.

Picasso's 1943 piece "Buste de Femme" being hung in Ramallah in June 2011

Photo via Abbas Momani/AFP via Getty Images

This had been a two-year process to make happen. As Al Jazeera notes, “Because of the occupation and inherent limitations on Palestinian sovereignty, what is ordinarily a straightforward loan from one museum to another suddenly took on a political, diplomatic and military character.” This included insurance, which presented a real risk from Israeli Occupation Forces invasion(s) into the area.

A representative from an insurance company in The Netherlands looked into it and saw the Oslo Accords had no basis of understanding for how it could travel to the country, noting “Oslo missed out on one of our basic fields of work: art and culture.” Eventually, they worked out the logistics.

The International Academy of Art Palestine’s gallery was actually located at the same place where Sliman Mansour had opened Gallery 79 for The League of Palestinian Artists a few decades prior, which had been forcibly shut down.

Mansour himself was the first person invited to be on hand for the arrival of the Picasso. It was exhibited in a very small area that had all sorts of regulations for the room, 24/7 security, limited people at a time, and more.

The Picasso in Palestine exhibit in 2011

Photo via Khaled Hourani

Hourani saw the project was a way to point out the realities of Palestinian life, and how bringing a painting like this could be so difficult. “What should be normal is bringing a Picasso,” he said. “The thing that should stop is the occupation.”

The Dutch museum who had provided the painting felt it was important, too. “Our Picasso will be changed by its journey to Ramallah, it will take on extra meaning and the story will remain a part of the history of the painting from this moment on,” said Charles Esche, then director of the Van Abbemuseum. “It feels like we are constructing new histories with such a project.”

Another aspect of it was that Hourani hired a filmmaking crew to document the journey of the idea, as he wanted to capture whatever happened – even if it hadn’t been successful in bringing over the painting. This footage turned into a documentary that was then released in 2015 about the whole process.

In addition, Hourani also later created his own paintings tied to the exhibit as well.

Picasso in Palestine #3

Painting by Khaled Hourani, 2019

Community of Arts Groups

In 2012, the Qalandiya International was founded as a biennale exhibit that was described as a culmination of efforts from seven significant Palestinian cultural institutions who focused on contemporary art and the cultural landscape of Palestine.

This included A. M. Qattan Foundation, Al Ma’mal Foundation for Contemporary Art, The International Art Academy of Art Palestine, Palestinian Art Court – Al Hoash, Riwaq, Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center, and the Nazareth House of Art and Culture.

The choice of the name and location in Qalandiya had significance, too:

“For the past decade, Qalandiya has been associated with the Israeli checkpoint that continues to suffocate the West Bank, disconnecting it from Jerusalem and the rest of the world. This checkpoint has been highly pervasive in the media and in the visual and literary works produced in and about Palestine. Countless stories about daily suffering and subjugation take place there, offering sad but true glimpses of the oppressive regime of the Occupation.”

In 2014, other art groups also joined as partners – such as The Palestinian Museum, Arab Cultural Association, Etiqa Group, Shababik for Contemporary Art, and more. It took place across multiple Palestinian towns and villages including Al Quds, Haifa, Ramallah, and Hebron. It also took place in Gaza, only a few months after the nearly two-month IOF invasion there in the summer of that year.

In 2016, the third and so far final rendition of the exhibition took place in multiple areas including inside Palestine but also outside of it (Beirut, Amman, and London). There was also a 2018 exhibition. It’s unapparent if it stopped in 2020 due to the breakout of the coronavirus pandemic or other reasons.

The Fish of Hebron

by Mohammad Shaqdih, 2016

2016 Qalandiya International

The A.M. Qattan Foundation, one of the founding partners, also continued their own efforts – including their own biennale program of the Young Artist of the Year Award that had started in 2000. It ran through 2020, awarding 11 artists in total over that time.

Another important initiative is Dar Jacir, otherwise known in full as Dar Yusuf Nasri Jacir for Art and Research. The location is the Jacir’s family’s 19th century home in Bethlehem, which had been built in the 1880s and often became a place for neighbors and travelers to get free meals, developing a reputation for the saying of “the food is at Dar Jacir.”

The house was lost to bankruptcy in 1929, after which it was used as a prison and army base by the British during the Mandate period. It was later bought again by another Jacir family member in 1980. Then in 2014, Yusuf Nasri Jacir had become sole owner of the property and wanted to turn it into a cultural center. His daughters, artist and filmmaker sisters Annemarie Jacir and Emily Jacir, became Co-Founders of the space. (Currently, is Emily is co-director with Aline Khoury.)

Since the Apartheid Wall started going up in the early 2000s, it has severely cut into and divided Bethlehem – in particular right near the Jacir home. The building is a couple hundred feet from the wall and close to a checkpoint, an area where there have often been groups of protestors against the occupation. As of 2017, the area nearby – including the Aida refugee camp – was deemed the most teargassed location in the world.

Dar Jacir house, shortly after being built in the 1880s

Photo via Dar Jacir archives

Dar Jacir house, modern day

Photo via Aline Khoury

Dar Jacir initially opened as a space for art and culture and then in 2018 they started offering residence programs for artists, giving Palestinian and international artists the chance to work in the area while working on their own projects.

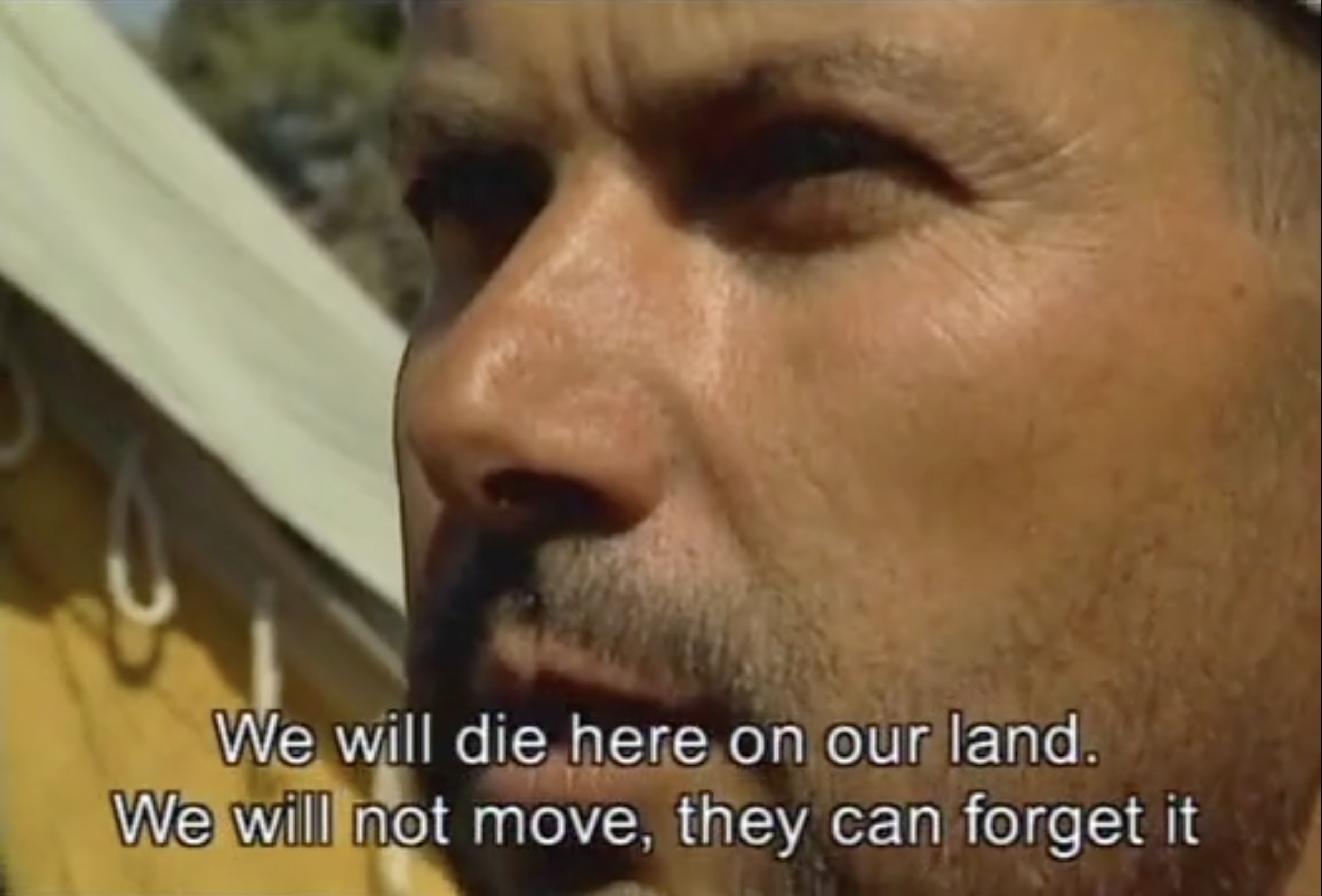

The IOF has since raided the Dar Jacir facility multiple times – kicking doors in, breaking windows, and stealing equipment. Despite the property destruction, expenses, and inhibited lifestyle – the Jacir family refuses to move.

The artists also interact with the community through workshops, tutorials, collaborations, and more. Dar Jacir helps "facilitate and foster cross-cultural exchanges building bridges between participant and local artists as well as diverse organizations, community centers and school internationally.” They also have a research center devoted to their Ottoman archives.

It operates independently, without funding from governmental agencies and others, in order to maintain full freedom for the artists.

Plaque for Dar Yusuf Nasri Jacir for Art and Research

Created by artist Tai Pomara for the house, 2019

via Dar Jacir archive

In addition to being a Co-Founder of the space, sister Annemarie Jacir continued to make her own personal work. She followed up her aforementioned debut feature film Salt of the Sea (2008) by making two other features in the decade – When I Saw You (2012) and Wajib (2017).

Emily Jacir, in addition to her work at Dar Jacir, has made art across a variety of mediums. Noteworthy here, she released a documentary called Letter To A Friend (2019) that looked at the history of the family home and surrounding area. For Emily, Dar Jacir is “the root, the very anchor — indeed foundation — to my entire practice as an artist. You could say everything radiates out from here. This is my center.”

In 2015, Dar al-Kalima University in Bethlehem also started the annual Ismail Shammout Fine Art Award, which was arranged and named in honor of Shammout’s legacy to Palestinian visual arts. and is still ongoing. These are a selection of the way arts groups further emerged during the 2010s.

Internet and Social media

At the time of publishing The Origins of Palestinian Art in 2013, Bashir Makhoul and Gordon Hon had written that “Palestinian artists are using the internet in lieu of official, institutional territorial networks and adequate gallery and studio space, and also as a site or medium for the production of art.” They also acknowledged that the same existing power structures still brought some issues of censorship and control. They proposed that “virtual spaces may become more valuable as sites of cultural development.”

This was evident with artists like a young Malak Mattar, who began to share her work online – making her first post in 2015, when she was 15 years old, after started to pursue art intently after the 2014 attack on Gaza by the Israeli military. Mattar soon developed an audience online that translated into other real-life opportunities, many of which she was limited due to her life and rights to travel as a Palestinian in Gaza.

Malak Mattar and a 2019 painting

via artist archive

Painting by Malak Mattar for the 2018 Greenbelt Festival in England, a Christian-based arts and cultural annual event

Looking back at the archive of timing for Palestinian artists sharing on Instagram, it seems younger artists like Mattar were organically quicker to embrace the medium – whereas some older artists began posting to it in the latter years of the 2010s, showcasing an ongoing mixture of past and new work. Some of these artists who are particularly active, like Sliman Mansour, have found an entire new generation of viewers.

In the 2018 dissertation of Sascha Manya Crasnow – The Next Generation: Shifting Notions of Time, Humor, and Criticality in Contemporary Palestinian Art – she also writes that this period impacted both the distribution of Palestinian artist’s work as well as their exposure to other art and information from around the world.

“The rise of the Internet has made the exhibition of digital works internationally possible with the click of a button, even if the artist cannot cross the transnational borders. In the same way, exposure to international work, cultural references, and audiences has increased because of the accessibility of media and sharing opportunities made possible by the Internet. Whether or not artists can travel in and out of Palestine, their accessibility to arts production around the globe is a greater possibility in the post-Oslo world than ever before.”

Crasnow points out that artists grew to have a specific emphasis on digital media forms, too, due to the ease of transfer and transportation. That being said, the visual art produced still included a range of mediums such as painting, sculpture, installation, photography, and video.

Art During Attacks

British-Palestinian filmmaker Rosalind Nashashibi had taken a trip to Palestine to make a new short film. Previously she had created works in the West Bank, where her family came from, but this time Gaza was her subject matter. It took her a long time to receive permission to be able to enter, but finally in 2014 she made it there.

However, her time filming was cut significantly short by the start of the next Israeli military assault on Gaza – the largest of the decade, lasting for two months that summer.

Regardless of not being able to complete the production process, Nashashibi managed to capture a variety of great footage that became Electrical Gaza (2014). The short also contains brief animation sequences that are sprinkled in, reflecting scenes from the actual film.

Electrical Gaza (2014)

by Rosalind Nashashibi

Electrical Gaza (2014)

by Rosalind Nashashibi

Electrical Gaza (2014)

by Rosalind Nashashibi

Electrical Gaza (2014)

by Rosalind Nashashibi

Another Palestinian artist, Nidaa Badwan, started to create her 100 Days of Solitude series of self-portraits in 2013, the name a nod to the novel One Hundred Years of Solitude by Colombian author Gabriel García Márquez.

In particular, Badwan cited Márquez’s use of magical realism, which she aimed to infuse the spirit of in her work. Each image would take weeks to devise and find or create the resources for.

Over the course of 20 months, Nidaa Badwan did not leave her 100 square foot room to face the outside world. Inside, in her war-imposed withdrawal and isolation, she created-and photographed-an immersive world of her own. Safe and free in this small oasis, she produced a series of stunning self-portraits, a project she calls 100 Days of Solitude, an homage to the landmark novel of magical realism by Gabriel García Márquez.

100 Days of Solitude series, Code 12

by Nidaa Badwan, 2014

100 Days of Solitude series, Code 4

by Nidaa Badwan, 2014

The 2014 invasion had brought damage to 20 cultural centers in Gaza from the Israeli military attacks.

Four years later, in 2018, there was a targeted airstrike on the al-Meshal Foundation cultural center in Gaza – which was primarily a theatre space, but also a hub for all artists to come together.

Then 18-year-old photographer Alaa Qudaih told Middle East Eye that she would go often.

“I used to visit the al-Meshal centre regularly because I am interested in art and theatre, especially since there are no real cinemas in Gaza. Instead of watching movies on the internet, I always loved to go there and watch people my age performing and simulating our reality in Gaza.”

After the airstrike, another 18-year-old singer Hazam Gusain led his twelve-man band in a performance on the center’s ruins.

The Middle East Eye article also mentions Alaa al-Gherbawi, then 26, who was working as an activity coordinator for the Palestinian Culture Palace, based on the fourth floor of the al-Meshal building. Gherbawi said it was not only a building, but a "cultural landmark" for the community.

Painting by Duniyana Al-Amour, 2021

Later, in August 2022, an Israeli airstrike on Gaza resulted in the martyring of 22-year-old artist Duniyana Al-Amour in her home in Khan Yunis, where she was in her bedroom.

Al-Amour was a visual arts student at Al-Aqsa University, where she was just about to graduate from.

In a tribute to her peer on Instagram, Malak Mattar wrote:

“To be a painter in Gaza is to expect death at any moment, while knowing that your paintings will live forever; to seek the safety of your paintings before that of your own self. It is to carry the pain of those around you from the moment you awake till the moment you sleep; to escape through paper and paint that the Occupation barely allows entry. It is to paint the anxiety, isolation and joy on the faces of the people around you, exhausted by siege and war.”

Both Mattar and Al-Amour grew up in Gaza amidst the myriad of attacks, unaware of a life of anything else.

Al-Amour once wrote on her Facebook page: “I am not making anything amazing. I am merely trying, amidst this isolation, to make life bearable.”

Desk of Duniyana Al-Amour, 2022

Photo by Abdallah al-Naami for Middle East Eye

Film Censorship, of Past & Present

In January 2021, after nearly two-decades of ongoing trials, the Israeli Supreme Court banned all future screenings of Mohammad Bakri’s Jenin, Jenin – the aforementioned 2002 film.

This was part of the a defamation and libel case by Israeli soldiers, who claim they were inaccurately portrayed as committing war crimes – despite Bakri simply allowing Palestinians to have a voice in telling their story from the Jenin invasion at the time. But the Israeli court nonetheless ordered Bakri to pay $70,000 in compensation to a military officer.

Additionally, this came after a similar defamation case that had been dismissed in 2003 by five Israeli soldiers. Yet 18 years after that, this decision was made against Bakri, a Palestinian filmmaker and actor who lives within the 1948 green line in “Israel.”

As Ramzy Baroud wrote in Mondoweiss:

“The background of the Israeli decision can be understood within two contexts: one, Israel’s regime of censorship aimed at silencing any criticism of the Israeli occupation and apartheid and, two, Israel’s fear of a truly independent Palestinian narrative…

To ensure the erasure of the Palestinians from the official Israeli discourse, Israeli censorship has evolved to become one of the most elaborate and well-guarded schemes of its kind in the world. Its degree of sophistication and brutality has reached the extent that poets and artists can be tried in court and sentenced to prison for merely confronting Israel’s founding ideology, Zionism, or penning poems that may seem offensive to Israeli sensibilities…

But the case of Jenin, Jenin is not that of routine censorship. It is a statement, a message, against those who dare give voice to oppressed Palestinians, allowing them the opportunity to speak directly to the world…

Jenin, Jenin is a microcosm of a people’s narrative that successfully shattered Israel’s well-funded propaganda, sending a message to Palestinians everywhere that even Israel’s falsification of history can be roundly defeated.”

Frame from Farha (2021)

Directed by Darin J. Sallam

Cinematography by Rachel Aoun

Later that year, in September of 2021, a feature film named Farha premiered at the Toronto Film Festival (TIFF), directed by Jordanian-Palestinian filmmaker Darin J. Sallam.

The coming-of-age film takes place in 1948 and tells the story of a 14-year-old girl in Palestine around the time of al-Nakba, who is hidden away by her father as the Israeli Occupation Forces invade their village and target civilians everywhere.

The grandparents of director Darin J. Sallam were exiled in the Nakba, but the story is based not their experience specifically. Instead, Sallam told TIME Magazine:

“There was a girl named Radieh who lived in Palestine in 1948, and she was locked in a room by her father to protect her from Israel’s invasion at that time. Radieh survived and walked to Syria where she shared her story with another girl. That other girl grew up, had a daughter of her own, and shared Radieh’s story with her own daughter—who happened to be me.

Because I’m claustrophobic, I kept thinking about what happened to Radieh. I felt for her. I related to her. Like every Jordanian of Palestinian descent, or any Arab, we grow up listening to stories about Palestine, of the Nakba. All these stories that I heard from my grandparents, families of friends, patched together to create the character of Farha, a name that means joy in Arabic. I chose the name because of how they talked about their life before the Nakba—to me it was life before their joy was stolen.”

Sallam wanted to focus on the character of the young girl who is filled with dreams, only to be forced to abandon everything in her existing life – including her father. She also felt that “There are no movies about this specific time in Palestine. It’s missing in cinema.”

Farha (2021)

Directed by Darin J. Sallam

Cinematography by Rachel Aoun

Over a year later, at the start of December 2022, Farha began streaming on Netflix worldwide. That was when it started to be attacked by Israeli officials and general public for the truth it shared about the Nakba, the founding basis of the “State of Israel.”

Israeli officials and social media influencers at the time condemned the movie, saying that its "whole purpose is to create a false pretense and incite against Israeli soldiers." Actions after included online smearing attacks against Sallam’s social media accounts as the director, a coordinated mass stream of negative reviews on IMDb, calls for a boycott of Netflix, and attempts to cut funding for a movie theater in Jaffa who snowed the film. These were among a variety of attempts to paint the film as fictional, antisemitic, and anything they could try to diminish the Palestinian narrative.

Sallam said she was not surprised by the reaction, but sees the refuting of the historic reality as a continuation of the crime. “Denying the Nakba is like denying who I am and that I exist. It’s very offensive to deny a tragedy that my grandparents and my father went through and witnessed, and to make fun of it in the attacks that I’m receiving,” she said in TIME Magazine. “I’m getting hateful, racist messages about who I am, where I come from, and about how I dress. This is not acceptable.”

Still photo from Farha (2021)

Directed by Darin J. Sallam

Photo by Mais Gammoh for TaleBox Production Company

A Pro-Palestinian campaign to support Farha was launched counteract the Zionist smear attacks, and it continued to receive praise from both viewers and critics alike. The film was also Jordan's submission for the Oscars that year in the Best International Feature Film category, though it was not selected as one of the 15 finalists for the award of the 93 worldwide submissions.

Overall, Palestinian films had picked up momentum in the digital area, since it became more accessible and affordable. According to the Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question, there were 799 films made between 1916 and 2005 – but then 547 films made between 2006 and 2019. While there was still continued difficulty of filming in the country, and raising funding, the progress was showing no signs of slowing down.

Zoom Out:

2000 - 2023 Overall

Looking back at some of the other observations and cultural moments in Gaza and the West Bank from the turn of the 21st century until 2023.

Art In First Quarter of Century

Since the late 1990s, and especially once the 2000s began, new mediums began to play an important part in Palestinian art – such as photography, video, installations, performance, and more.

Hot Spots, relating to worldwide geopolitical conflict

Installation by Mona Hatoum, 2006

However, it’s worth noting that didn’t mean that previous mediums faded away. Painting, for example, continued to remain a key method. And artists heeded advice from their elders and mentors, such as Bashar Khalaf who studied under Sliman Mansour at Al Quds University –continuing the long history of art being passed down, like with Daoud Zalatimo teaching Ismail Shammout prior to the Nakba.

Bride of the Homeland

Painting by Bashar Khalaf, 2015

Inspired by a 1976 painting of Sliman Mansour by the same name, commemorating teenage martyr Lena Nabulsi

One part of a larger Rituals Under Occupation work

Painting by Bashar Khalaf, 2015-2016

via Gallery One, Palestine

French-based anthropologist Marion Slitine wrote a piece for IEMed entitled Cultural Creations in Times of Occupation: The Case of the Visual Arts in Palestine, where she talks about the development of artists after the Oslo talks and a breaking away from work being strictly tied to political representation.

However, she notes, it’s not that artists didn’t continue to speak about their reality. Rather, she points out, that artists started to focus more on the consequences of occupation on Palestinians’ everyday life.

“In a more individualized approach to the national cause and collective involvement, the new generation of artists expresses self-criticism of Palestinian society, caught between neo-liberalism and political sclerosis since the failure of the Oslo Accords.

In this context, use of the codes of contemporary art and new technologies helps mark a rupture with the conventional political repertoire. The scene is moving from a purely nationalist art to one that tends towards universalism and considers art as a struggle for human right.”

Crossroad

by Raeda Saadeh, 2003

Moving

by Raeda Saadeh, 2003

Life In The Occupied West Bank

There may be a more active arts organization field in the occupied West Bank, but life in general is still incredibly restricted for the three million reside there.

Around 800,000 are refugees and 25% of them live in refugee camps that were established after the 1948 Nakba. The Apartheid Wall continued to be built after twenty years of expansion, with 85% of the wall within West Bank territory. At the end of 2022, the wall was still only at 65% of the planned building. The construction also led to the destruction of hundreds of Palestinian homes and forced tens of thousands to move further into the West Bank. One of the many groups impacted by this is agricultural followers. The Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question writes:

“Through the Separation Wall, Israel has managed to grab approximately 9 percent of the area of the West Bank and shrink the area of farmland there. In the 1970s, this farmland employed approximately 72 percent of the Palestinian workforce, but by 2020, this had dropped to less than 8 percent. The wall has annexed large swathes of fertile farmland, especially in the northern and western parts of the Tulkarm, Qalqiliya, and Salfit regions.”

Many areas have been negatively impacted by the way the wall divides their city, like historic Bethlehem, which has significant religious meaning. The Institute for Middle East Understanding notes that “Palestinians are able to use only about 13% of the land in the Bethlehem district.” Emily Jacir also describes this trajectory in-depth in her 2019 documentary, Letter To a Friend.

The city of Al Quds / Jerusalem, is also known for its history to several religions, and East Jerusalem in particular has been continually taken over by more settlers and the wall.

Part of the Apartheid Wall in East Jerusalem, blocking off an illegal settlement

Photo by Ahmad Gharabli/AFP

On an art-related side note, sections of the wall in certain areas has become a canvas for murals and graffiti, including by international artists who come to paint their own messages.

However, this has been criticized by Palestinians, especially of tourists who go to Banksy’s “The Walled Off Hotel” in Bethlehem where guests are encouraged to put their own graffiti additions. This is viewed as normalizing the occupation and the state of the wall itself, while there should be no border in place.

“We don’t have the privilege of writing on the wall, and then going home and never having to see this wall again. We are forced to see it every day,” said Amany Khalifa, a prominent Palestinian activist in the West Bank.

The art of Banksy, who has painted murals on the wall himself, has even been removed by the Israeli government and brought to Tel Aviv, exhibiting it in Zionist galleries – removing its intended purpose – and using it for their own profit.

One alternate example worth noting is of Italian street artist Jorit, who came and painted a mural of well-known Palestinian activist Ahed Tamimi, who at the time was 17-years-old and about to be released from Israeli prison days later.

Due to the nature of painting a figure of Palestinian resistance to occupation, Israeli officers arrested Jorit and another Italian artist with him – along with a Palestinian man from the nearby Aida refugee camp who was claimed to have also been with them. The two Italians had their visa’s canceled and were forced to leave the country.

Palestinian activist Ahed Tamimi

Photo by Beata Zawrzel / NurPhoto

It’s worth mentioning, from a digital archiving perspective, that searches for West Bank art most often shows articles and information connected to the wall – instead of actual artists there.

Along with the continued expansion of the “separation” wall, there has also been a continued increase in illegal Israeli settlements, which have only kept going up since the Oslo Accords. There are now around 700,000 illegal settlements of around 7 million people, as of the end of 2023, across the West Bank and East Jerusalem.

Not only have they taken land, but there are daily settler attacks against Palestinians to either try to steal more land and/or to harm them. It is not uncommon for them to gather into groups, violent mobs who carry out pogroms. These settler attacks are in addition to the constant presence and attacks from Israeli soldiers, including smaller raids happening everyday to larger invasions like in Jenin in the summers of 2022 and 2023.

In the West Bank, Mahmoud Abbas – also referred to by some as Abu Mazen – had been elected in 2005 with the Fatah-run Palestinian Authority (PA). While his term was originally set to last four years, he remained in power ever since.

Many Palestinians fighting for their complete liberation have spoken about viewing Abbas and the PA as collaborators and traitors. For example, as Israeli forces raid areas that the PA is supposed to have jurisdiction over, they do not do anything to stop the IOF. It is not only raids, however, it is the daily harassment, violence, restrictions, and more that people in the West Bank are forced to live under.

With the PA being especially unhelpful with security, local armed resistance groups have continued to carry the responsibility to protect their people. In 2022, there was an increase in armed resistance groups in the West Bank, continuing a long tradition. The most notable are the Jenin Brigade and the Lions’ Den. These groups are formed from residents in these areas, like those who grow up in the Jenin refugee camp and only know this life of constant attacks and restrictions.

“The freedom that everyone in the world enjoys, we don’t know what (that) freedom is. They come here and invade our camp and our homes. We haven’t traveled between cities, the borders are like we’re in prison. We’ve also never seen the sea,” says an anonymous Jenin fighter. “And they ask why we’re carrying arms? I have no other choice but to carry my gun and to resist until I die – because as things are now, I’m dead while I’m breathing.”

A Palestine-shaped installation at Jenin refugee camp

Photo by Wajed Nobani/APA Images, 2002

There are endless ways that Palestinian life is restricted in the area. To briefly share just a few examples:

There are hundreds of Israeli military checkpoints and road blocks, which provide a lot of difficulty for movement – imposing obstacles of working, social, and living conditions. Israelis on the other hand, as Al Jazeera notes, “can travel freely on their own ‘bypass roads’ which have been built on Palestinian land to connect illegal Israeli settlements to major metropolitan areas inside Israel.”

As of August 2023, there were over a thousand Palestinians placed in “administrative detention” without any charge, nor any trial. (And to note for context: 1 year later, this would rise to 10,000 Palestinians taken hostage through this system as of mid-2024)

Inside detention and in prisons, these Palestinians taken hostage are subjected to mental and physical torture. On average, they reportedly spend a year inside this confinement. Plenty are held for longer. Of course, this is not a new trend, but rather a longstanding practice for Israelis to throw Palestinians in jail unjustly with abhorrent treatment.

They are also the only country in the world to prosecute Palestinian children in military courts. All Palestinians are tried in this military setting, which have a 99.7% conviction rate for Palestinians. Israeli illegal settlers, on the other hand, are tried in a civil court.

Homeland (الوطن)

Painting by Sliman Mansour, 2010

The way to Bethlehem (الطريق الى بيت لحم)

Painting by Sliman Mansour, 2022

High unemployment rates, restrictions on trade, control of imports and exports, and the aforementioned takeover of farmland – these have all been ways that have prohibited Palestinian economy from flourishing, let alone being self-reliant and sustainable.

Even basic necessities like water are controlled, with a daily supply capped off below the World Health Organization’s recommended daily amount. Palestinians only get water every 15-20 days (put into water tanks). Meanwhile, illegal settlers have no limits on their water access and consume more than double the amount of Palestinians who live nearby.

House permits for Palestinians are for the most part rejected (95% of the time), and instead their homes are often bulldozed by Israeli authorities. To add insult to injury, the act of the actual bulldozing has to be paid for by the residents themselves (in addition to them now have to pay for new housing and items). The UN has said around 11,000 Palestinian-owned structures have been demolished from 2009 through the end of 2023.

Journalists have been repressed and targeted, like Al Jazeera’s Palestinian-American reporter Shireen Abu Akleh who was killed by an Israeli sniper in May 2022.

The list goes on and on of all the restrictions, those are just a sample. This whole page could be used to describe all the different methods of apartheid, repression, violence, and daily methods implemented to make their lives a nightmare.

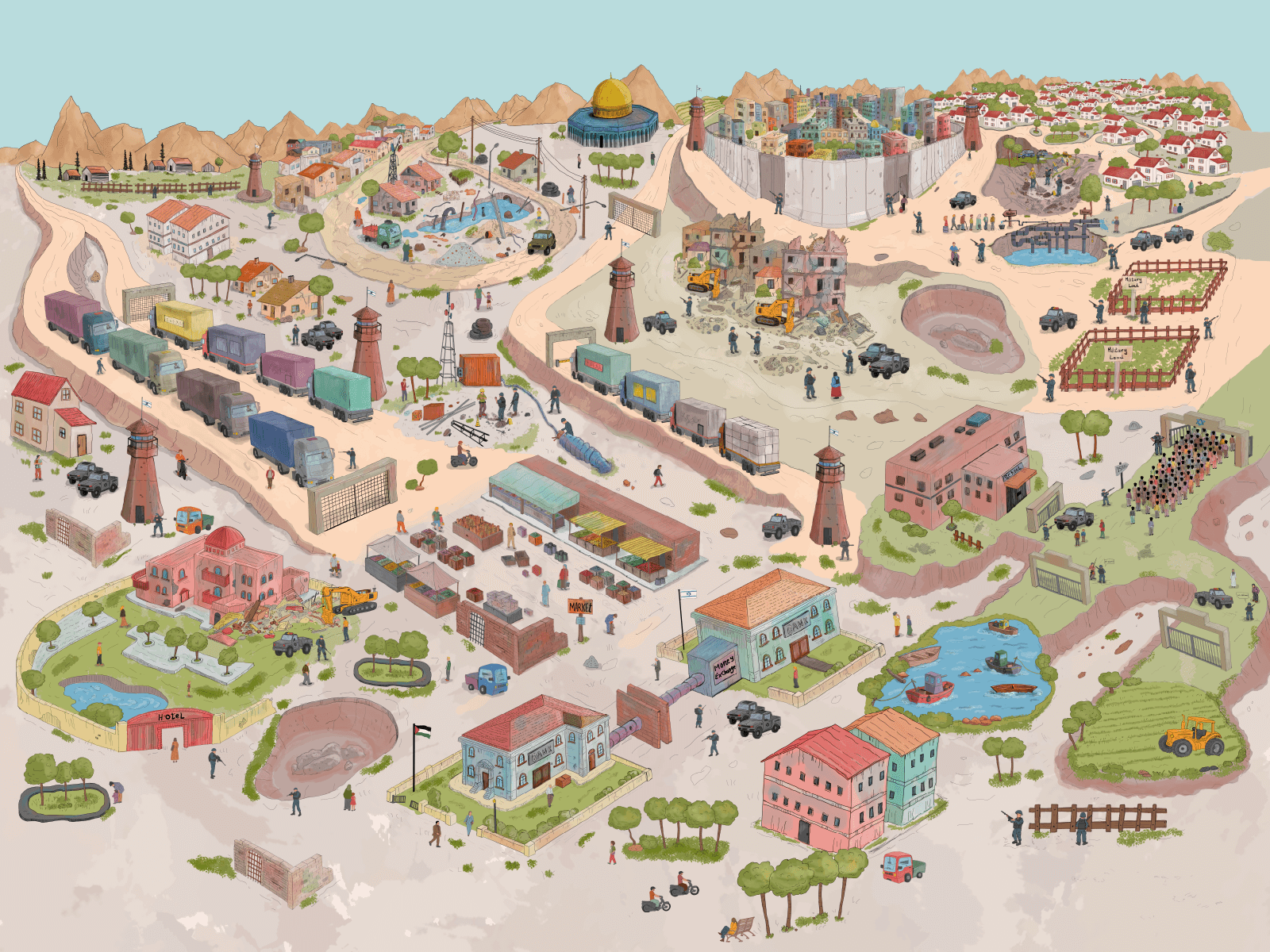

An illustration for Al Jazeera’s illustrated guide of Palestinian life under Israeli occupation

Gaza & The Great March of Return

It was very difficult Palestinians people in Gaza to receive permission to leave the enclave after the air, sea, and land blockade by Israel began in 2007, including for education or medical treatment.

Israel also banned nearly all exports and severely controlled imports, immensely harming Gaza’s economy and bringing about high unemployment.

The majority of population as refugees were packed into this tight area – one of the most densely-populated in the world – had little safe water to drink, were often dependent on aid for food supplies, and had electricity restricted to around four hours a day.

Attacks by Israeli Occupation Forces in the years after (notably 2008-09, 2012, 2014) at varying degrees left several thousands of martyrs, thousands more injured and handicapped, millions displaced, and all types of properties destroyed. This included the destruction of hospitals, schools, mosques, and UNRWA facilities. The longest was in 2014, which occurred in July and August that summer.

Shortly after, in the mid-2010s, UN agencies and officials declared that Gaza was past the point of being livable. Yet this continued to make no real change in international efforts to change it.

A Child's View of Gaza,

For a 2011 exhibit that was censored and canceled

via Middle East Children’s Alliance

A Child's View of Gaza

via Middle East Children’s Alliance

A Child's View of Gaza

via Middle East Children’s Alliance

A Child's View of Gaza

via Middle East Children’s Alliance

At the end of 2017, Ahmed Abu Artema – a Palestinian journalist, poet, refugee, and father – went out for a long walk one night. He ended up by the border fence of Gaza and “Israel” and saw the soldiers there ready to shoot at Palestinians who came near. At the same time, he witnessed birds moving freely along both sides of the fence. He made a Facebook post after asking why a bird can move freely, but not he as a human and as a refugee from the land being blocked.

A month later, in January 2018, he made another post sharing the idea for large peaceful protests at the border fence where Gaza residents could pitch tents for a makeshift setup, raise Palestinian flags and keys of return, and aim to enter the occupied territories across the border. At the end, he used the phase of the Great March of Return.

The idea spread and bubbled with enthusiasm from Palestinians who wanted to participate, ultimately taking the form of weekly Friday protests. The first one was March 30, 2018, to commemorate Land Day (circa 1976). The goal was to demand the right of return to their land – as enshrined under international law – and an end to the siege and blockade on Gaza.

Great March of Return in Gaza

Photo via Khalil Hamra / AP

Palestinians gather at the Gaza border on March 30, 2018 as the initial Great March of Return protest. Israeli soldiers in foreground on bottom left.

Photo by Jack Guez / AFP / Getty

Palestinians marched to the area near the border, along the fence that closed off Gaza from the rest of the country. In the first protest on March 30, 2018, Israeli Occupation Forces responded by sending down tear gas and toxic chemicals on the civilian protesters.

The weekly protests of the grassroots movement continued. In 2018, from March 30 to May 14, they were described as overwhelmingly nonviolent - with people of all ages gathering together to resist and celebrate life.

During this period, of less than two months, there were around 100 martyrs. On the first day alone, Israeli snipers had targeted and martyred 15 Palestinians.

Nonetheless, the protests continued. Tires were burned by some as a way to hopefully deter Israeli snipers from continuing to shoot people, as it made it more difficult to see through, but it didn’t stop soldiers from firing away.

Tear gas canisters fired by Israeli forces fall down on Palestinian protestors, in the midst of smoke from tires burning, during the Great March of Return in Gaza, August 2018

Photo by Mahmud Hams / AFP / Getty

There were was a section of protestors who responded to the violence on their community by throwing rocks, using slingshots, molotov cocktails, or other DIY means against the highly-armed Israeli military that stood guard on the other side.

These protestors often tried to get closer to the fence, sometimes in attempts to try to cut the barbed wire or damage the fence, though they were still shot at within at least 300 yards.

Palestinians at the Gaza border fence, during the Great March of Return, as Israeli snipers take aim at them

Photo via Mohammed Abed / AFP / Getty

One photo of young civilian, Aed Abu Amro, spread widely online and was compared to an 1830 painting, Liberty Leading the People, that commemorated the July Revolution of 1830 that toppled King Charles X in France. Amro was later shot on multiple occasions by Israeli snipers during another protest later in 2018, injuring him significantly and stopping him from returning.

Palestinian civilian Aed Abu Amro during the Great March of Return

Photo by Mustafa Hassouna / Andalou Agency

Liberty Leading the People

French painting celebrating the July Revolution in 1830

Painting by Eugène Delacroix

Compared to Mustafa Hassona's photo of Aed Abu Amro at the Great March of Return

A’ed Abu Amr on October 22, 2018

Painting by Nala J. Wu - @naladraws, published 2024

While the Israeli military may claim they felt they were in danger, there was only 1 soldier killed and 7 injured.

Amnesty International declared that it had "not documented any instances where protesters posed an imminent threat to the lives of Israeli soldiers and snipers, who have been located behind the fence, protected by military equipment, sand hills, drones and military vehicles."

The Great March of Return art

Drawing by Seth Tobocman for The Nation, January 2024

Israeli soldiers shot at children, journalists, medics, disabled people, and unarmed protestors. The injuries caused were most often from tear gas, rubber bullets, or live ammunition.

The IOF specifically targeted people from the knee caps down to inflict life-changing injuries that often paralyzed them.

One of the martyrs targeted by Israeli snipers was Razan An-Najar, who was wearing a white coat designated for medical staff. She was over 100 yards away when she was fatally shot.

Great March of Return martyr, 21-year-old Razan An-Najar

Painting by Malak Mattar, June 2018

Artist Malak Mattar paid tribute to An-Najar in a painting and shared the following statement with it on Instagram:

“Razan An-Najar represents every Palestinian, she represents our resilience, our connection to the land and our willingness to face up against oppression no matter the consequences.

Razan was 21-years-old and volunteering as a nurse when she was taken from us. She helped treat more than 70 injured people since the 30th of March and faced the threat of gunfire every time she attended another…

As a Gazan girl just a few years younger than Razan, I can't express how much pain I feel. I have spent countless hours in tears, her soul was truly pure and makes me proud to be a Palestinian.”

By the end of the Great March of Return there were around several hundred martyrs and tens of thousands injured.

The protests were announced to be suspended around the start of 2020, tied to ongoing government negotiations between Hamas and “Israel” – and then the coronavirus put them to a more emphatic stop.

Great March of Return collage, featuring photos from journalists on the ground at the protests.