Jenin, Jenin (2002)

Mohammed Bakri was born in 1953, five years after the 1948 Nakba, in the village of Bi’ina. This was near the Palestinian city of Akka, which became under Israeli occupation after 1948.

There was no electricity in Bi’ina when Bakri growing up. However, he still managed to fall in love with cinema by the time he was six years old. This was because a local electrical engineer managed to get a projector to connect to a generator. As he screened movies for everyone, the engineer also humorously translated the words or ideas of the films as they went.

Bakri began his career by acting in theatre plays and movies. He had his first play in 1977, an adaptation of Arthur Miller’s A View from the Bridge, and made his movie debut at 30, playing a Palestinian character in the film Hanna K. He became known for his acting over the next two decades. As Middle East Eye notes in an article on his career, Bakri managed to avoid taking on the many roles that were racist Arab stereotypes and instead often found ways to deepen the characters he played.

After a couple of decades acting, Bakri found himself behind the camera. "Acting for me was truly a choice," Bakri said in a 2009 video profile. "Directing wasn't a choice, it was a reaction." This started with his 1998 feature, titled 1948, to commemorate 50 years of the Nakba and share the Palestinian side of the story from his father and grandparents who had experienced it.

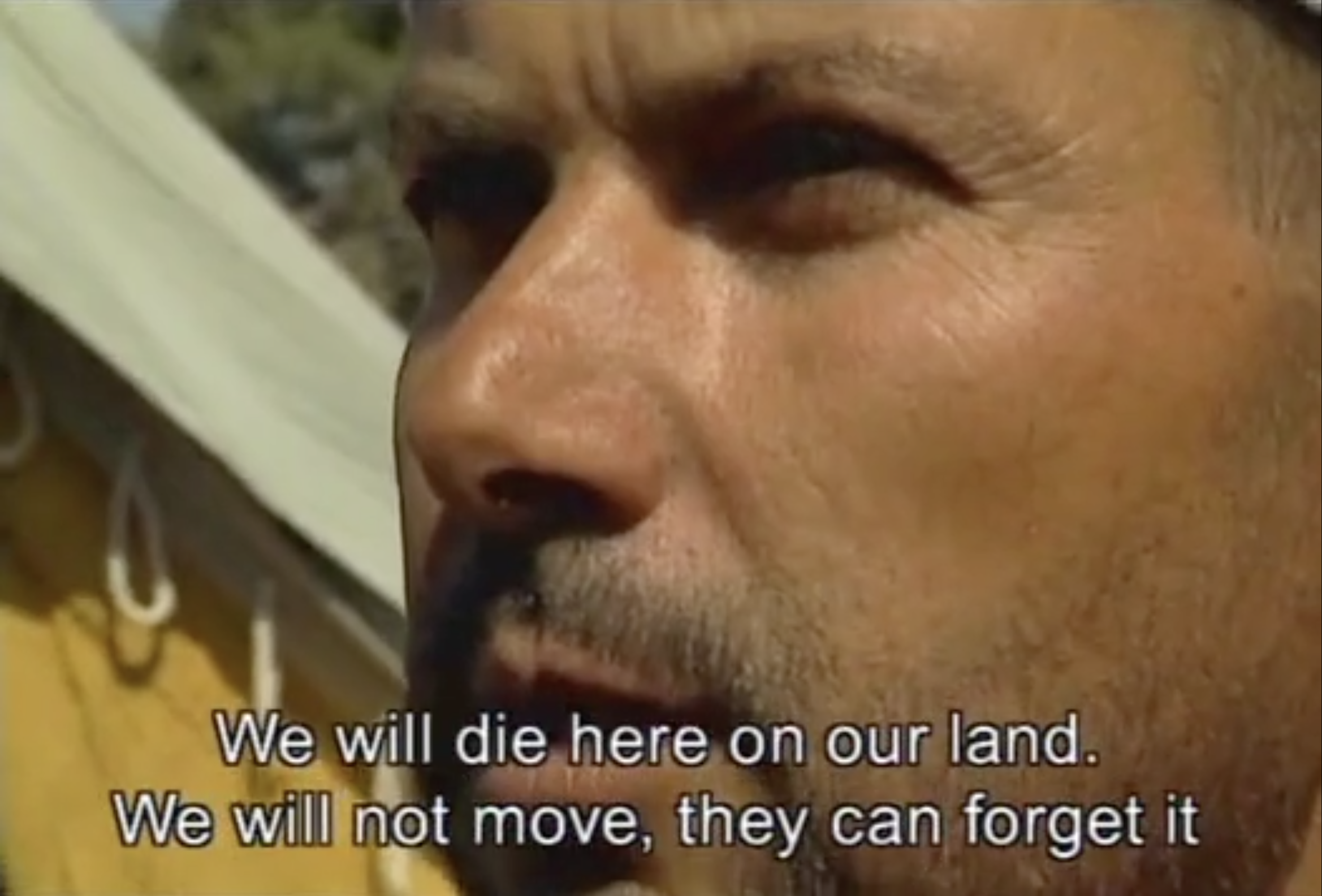

Most people, however, know Bakri for his 2002 documentary – and the main focus of this feature – which is Jenin, Jenin. That film takes place after the Battle of Jenin between the IOF and Palestinian resistance in April 2002. It primarily features residents of the refugee camp speaking about their experience with what had just happened.

Jenin, Jenin was filmed in the Spring of 2002 and premiered in October that year, to the fury of the Israeli army, government, and public. Through the years it’s gone through various attempts at being banned – successful, then later overturned, then banned again.

Jenin is a city, in the occupied West Bank, which has always been a central point for the Palestinian resistance.

The Jenin camp was established UNRWA in 1953, the same year Bakri was born, after the previous iteration was destroyed by a snowstorm. It became a home for refugees from more than 50 villages and cities in the northern parts of Palestine, especially Haifa and Nazareth.

During the 1967 Al-Naksa, otherwise known as Six-Day war, around 300,000 more Palestinians were displaced. During this time, Israel had seized control of the West Bank – and, thus, Jenin.

This was in place until the Oslo Accords deal transferred it to the Palestinian Authority in the mid-1990s. However, the Oslo process did not result in anything tangible, and no goals or deadlines had been met by 1999. During this period, between 1993 and 2000, the amount of Israeli settlers who established illegal settlements in the 1967 occupied territories (Gaza and West Bank) had doubled from 200,000 to 400,000. The tension grew as a result of the failed peace talks.

In 2000, the Second Intifada began (eventually lasting until 2005). As Al Jazeera describes, “Then-Israeli opposition leader Ariel Sharon sparked the uprising when he stormed Al-Aqsa Mosque compound in occupied East Jerusalem with more than 1,000 heavily armed police and soldiers on September 28, 2000.” (Site note: Sharon was later elected Prime Minister of Israel from 2001-06, bringing with him a longtime military history).

After initial demonstrations of nonviolence were met with excessive force and mass firing of ammunition for over a month, Palestinians were left with no choice but for armed resistance to play a central role in the uprising. This included suicide bombings, rocket attacks, and sniper fire.

On March 27, 2002, a Palestinian suicide bomber killed 30 Israeli’s and injured 140 who were at a hotel’s Passover seder. It was the largest attack against Israeli’s during the Second Intifada. As Bakri later says, "This attack gave the green light to Sharon's government to declare war and re-occupy the West Bank."

Israel then launched their “Operation Defensive Shield” a couple of days later, on March 29, in what would turn out to be the largest attack on the West Bank since 1967.

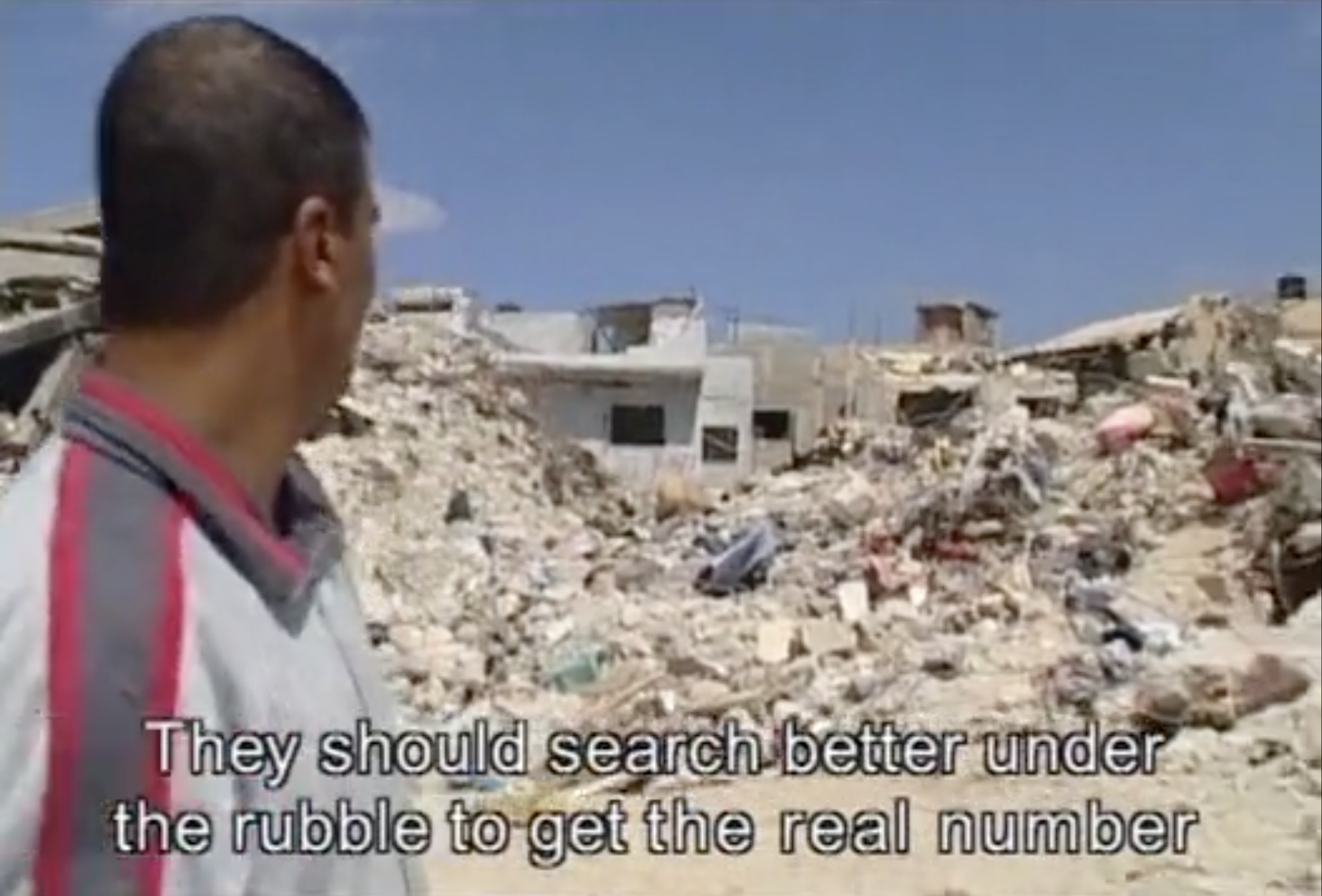

After targeting other towns, Israeli occupation forces invaded Jenin and the refugee camp on April 3. This led to ten days of intensive fighting and destruction. At this time, there was an estimated 14,000 people within a 0.2 square mile area.

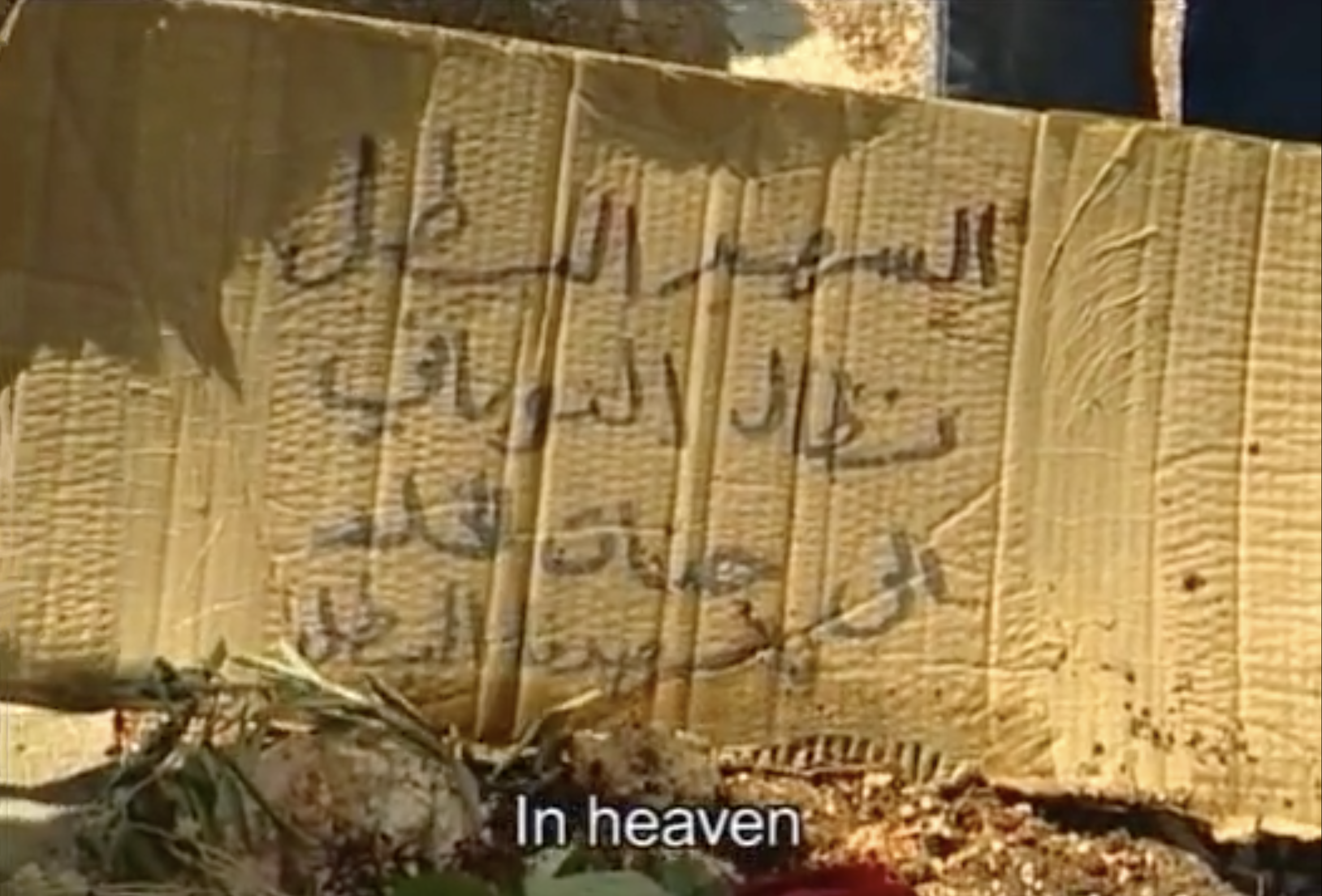

By the end of the battle on April 11, 2002, around 50 Palestinians were reportedly martyred – though many expect the number to be higher. At least half of those counted were civilians.

Israel had 23 soldier casualties in the battle, ultimately unable to eliminate the resistance forces.

The damage was everywhere. With 150 tanks and a dozen armored bulldozers, the Israeli occupation forces destroyed and damaged hundreds of homes, razing many to the ground. F-16 fighter jets and Apache helicopters also attacked the camp from above.

During the 10 days of the invasion, the IOF refused to allow in humanitarian aid from entering. They denied entry to everyone from medical teams to journalists to a UN commission of inquiry – claiming it was for their own safety.

Over a quarter of the camp’s population was also displaced, with 13,000 refugees fleeing the area.

As the Jenin invasion happened, Bakri was acting at a theatre in Nazareth, putting on the play The House of Bernada Alba as the role of a female widow and mother.

Bakri and his co-star – Valentina Abu ‘Aksa, who played his character’s daughter – went to Jenin to be part of a protest at the al-Jalma checkpoint, which is north of Jenin and separates it from the ‘48 occupied territories and the West Bank.

During this gathering, the IOF shot into the crowd and injured his co-star, who was standing at his side. "If the soldier passes by and shoots at us like that, when we are standing – (then) how will he behave inside, in Jenin,” Bakri said about what was happening in the camp, where no one had been allowed in. “It was at that moment that I decided to enter Jenin with a film camera.”

Bakri snuck in by driving the long way through the mountains, in a risky journey with a cameraperson and sound operator, and they filmed over the course of five days and nights.

In the film, Bakri lets the refugees in the camp speak in their own words. He wanted to show the other side:

“As a Palestinian living in Israel, I have always heard two different stories: the Israeli story and the Palestinian one. Throughout my life, I’ve heard the Israeli story in the street, in kindergarten, at school and university. It was forbidden to hear the Palestinian narrative. Even the word ‘Palestinian’ is considered a slur to this day…

I have also read Palestinian literature that I had been prevented from reading for many years. My political awareness and identity slowly coalesced. I came to realize that I had a human and a moral duty to tell a different story from the Israeli story.”

Site note: Jenin, Jenin is available to watch, in full, on YouTube. (54 mins)

Use the player below to view. Press the center play button below to view.

The film itself presents no other information besides these local refugee testimonies, nor does it pretend to be the definitive recap of what transpired. This is where critics try to use the word “documentary” against it. "I never said or declared that I have a monopoly on the whole truth,” Bakri said. “Nobody has any monopoly on the truth. I am telling my truth. It is the truth of my people.”

Anyone who actually watches the film can quickly see this clearly isn’t a straight-forward, run-of-the-mill “documentary.” Bakri intentionally does not give any other context, he jumps between interview clips with occasional vignettes. Even these vignettes, and the accompanying music score, contain scenes reminiscent of a filmmaker like a David Lynch in the sometimes surrealist or abstract moments.

Overall, the editing is quick and fluid – it does not linger and the timing of a cut is often used to add a certain effect to a moment.

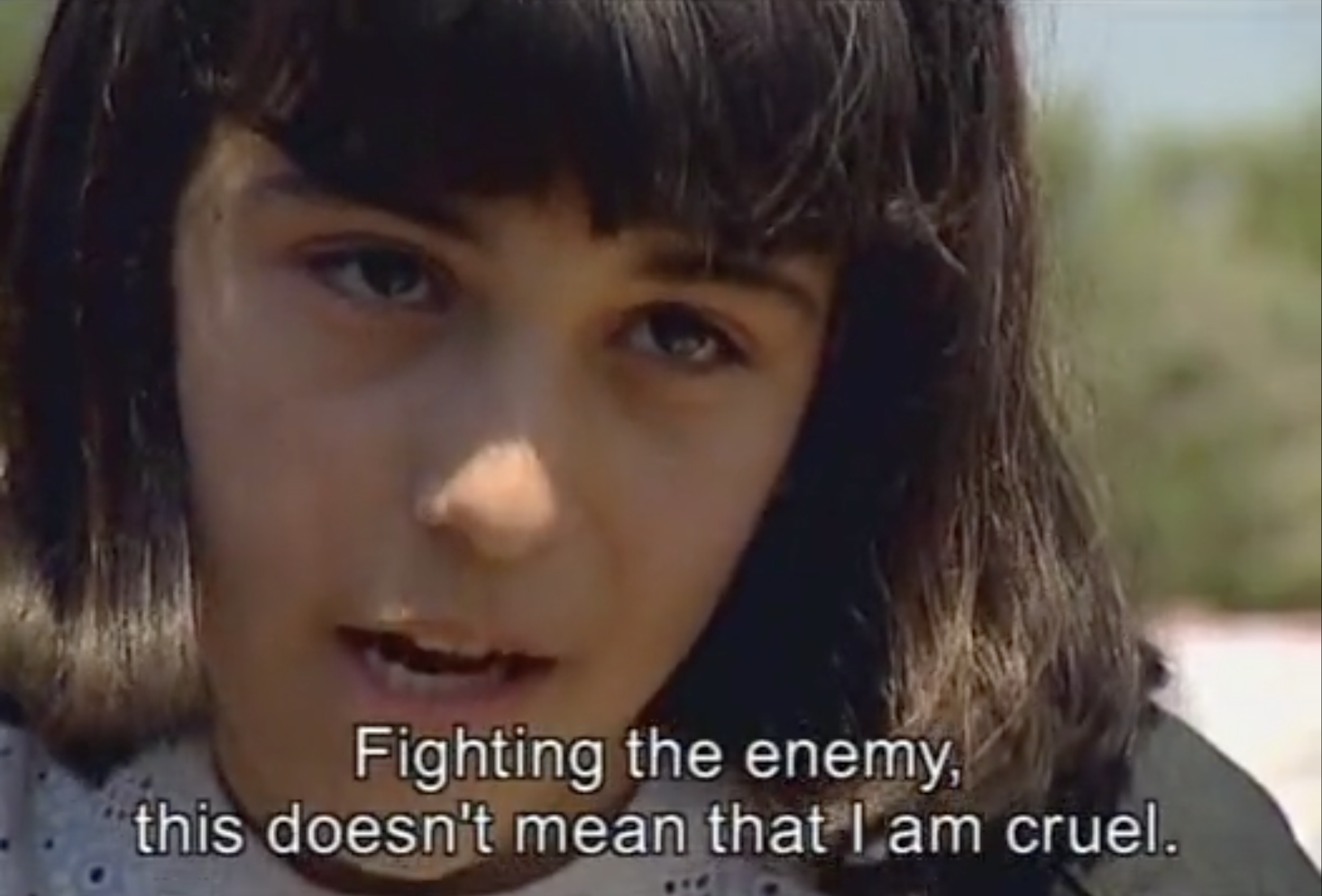

There are also thematic cuts in the editing. One adult man speaks about how Palestinians thought all of this would be traumatizing for their kids, but in fact his son does not even fear the planes anymore and can tell what every different type of attack is. The man says he thinks if you talk to any of these kids, he bets they will respond with the utmost courage. The film then cuts to a young girl of the Jenin refugee camp, who we’ve seen speak already at this point.

The young girl of the camp delivers one of her most impactful moments, often shared on social media these days, where she starts by saying (translated): “I am not afraid of these cowards.”

She is a striking example of the overall Palestinian resilience shown in the film. That despite all of these inhumane attacks by Israeli forces, they will not be deterred. They will not leave their land, they will continue to rebuild, and they will never give up.

Jenin, Jenin then premiered at the Cinematheque in “Tel Aviv” on Oct. 28, 2002. Immediately when it came out, the film became a target by many Israeli soldiers, government personnel, and citizens. At the start of 2003, the Israeli Film Censorship Board had banned the film from playing in the country. (Bakri and his son sold video copies on the street in the meantime.)

Israeli soldiers and commanders of the Fifth Brigade – the armed forces on the ground in Jenin for this battle – were vehement about the “wrong” way they were portrayed in the film. Five reserve soldiers in particular filed a libel suit against Bakri.

An article from 2003 in Haaertz, a leading Israeli newspaper, notes that the argument essentially could be summed up that Bakari “portrays us as war criminals and murderers, as the perpetrators of a massacre, and effectively, without explicitly saying so, as Nazis.” (Site note: It may be worth noting the Palestinian adage, “Every Zionist accusation is a confession.”)

The Haaertz article also describes the pressure put to stop it from being shown internationally:

“As for the film's distribution abroad, Gideon Meir, deputy director general for information and media in the Foreign Ministry, described numerous actions taken by the ministry to block the film's screening abroad in a letter to Caspi dated September 4, 2003. The letter calls the film ‘a terrorist attack against the truth by cinematic means.’”

A large amount of the court debate was whether the film was a documentary in representing historical truth or just an artistic vision of the director.

As deliberation of the case continued on throughout the year, the ban was reversed in November 2003.

Yet Bakri was still facing a lawsuit from soldiers for defamation of character in the years that followed, though no specific soldiers are shown in the film and none are mentioned by name.

The case dragged on all the way until 2011, when the Supreme Court judges said that while they declared the film to contain inaccuracies of the facts and did portray the Israeli forces negatively, “the plaintiffs were not specifically identified in the film and therefore did not have standing to claim that they were personally defamed.”

However, the legal proceedings did not end there.

In 2021, the defamation case of an army colonel was picked up by an Israeli district court about his connection to the film. There is a scene of an elderly citizen who talks about being threatened by the colonel to shut up or be killed. The colonel said this hurt his reputation and the court ruled in his favor.

So nearly twenty years later, in 2021, Israel again banned screenings of the film. All copies were also ordered to be seized. In addition, Bakri was told to pay $55,400 in damages to the colonel.

In a 2021 article for The Palestine Chronicle after the decision, author and journalist Ramzy Baroud wrote:

“The background of the Israeli decision can be understood within two contexts: one, Israel’s regime of censorship aimed at silencing any criticism of the Israeli occupation and apartheid and, two, Israel’s fear of a truly independent Palestinian narrative.”

Bakri appealed the decision, but the Israeli Supreme Court rejected it in November 2022.

Bakri’s first film, 1948, had been motivated by his desire to tell the Palestinian side of the story. With Jenin, Jenin he wanted to do that again and capture the stories that would not be covered in the news. “I tried to give expression to the outcry of the people in the camp who have lived for decades under Israeli occupation,” he said.

In a piece for Haaertz, talking about the endless attacks on him since the film’s release, Bakri said:

“I never anticipated the crude and savage attacks on me and the film. I was called a murderer, a liar, a hater of Jews, an anti-Semite, a terrorist. The film was described as being all lies and manipulation. People claimed that I distorted the truth. There were calls in the Knesset to boycott me. And along with the media lynching, I received hundreds of threatening letters directed at me and my family. They incited against me and called for my blood.”

Bakri had made another film – Since You Left (2005) – which reflects on the time since the passing of his mentor and friend, writer and politician Emile Habib, who had passed in 1996. As another movie far from a traditional documentary, it showcases different forms and styles. It’s a very personal creation, and a significant portion sheds light on his life around the release and controversy around Jenin, Jenin.

*Watch both parts of Since You Left above (58 mins)

In a 2021 interview, Bakri was asked if he still would have made the film if he had known he would be persecuted, targeted, and smeared for over 20 years. “Of course, I will do the same film,” Bakri said. “I must tell my story. How can I regret telling my story.”

Violence against Jenin has continued without end over the years on the 14,000 refugees within the 0.2 square mile camp – such as a large scale raid on the 20th anniversary of the April 2002 invasion, there was a large-scale raid, a July 2023 invasion that was the biggest in two decades, and then a 10-day siege in August 2024 under Operation Summer Camps that was the largest since the Second Intifada.

Bakri made a sequel Janin, Jenin about the July 2023 attack, which premiered in August 2024 in Ramallah and raised money for Gazans in need. It was subsequently banned by Israeli police. It has yet to be made available online besides a brief week-long run on the Palestine Film Institute.

Jenin has continued to be subjected to endless raids to this moment. The Israeli view of Jenin’s refugee camp is that it’s “a breeding ground for local terrorist groups.” This way of Zionist thinking has not changed over the years and continues to be used as a reason to deplore endless violence.

“There are two places in Palestine that Israel has never been able to fully conquer – Jenin and Gaza,” Diana Buttu, a Palestinian political analyst and lawyer, told Al Jazeera. “That’s why Israelis try to bring down the people of Jenin and Gaza… time and time again, but it’s never worked.”

A Palestinian mother and camp resident added: “Jenin has and always will be a source of Palestinian resistance.” In a different Al Jazeera article, another Palestinian gives a quote that exemplifies the same spirit that you see in Jenin, Jenin: “They are taking their anger out on the camp. They are unable to destroy the resistance, or our camp, or to break our spirits, or make us afraid,” he said. “Inshallah, we will remain a thorn in their eyes.”

With the world of social media spreading the reality of Israeli actions on a daily basis, Palestinians like those featured in Jenin, Jenin now have a way on their own to help share their stories with the world.

Palestinians now directly send out frequent messages, photos, videos, and stories to people everywhere. From the livestreamed genocide in Gaza to the ongoing attacks in Jenin being captured on cellphones, people can see the truth. As a result, the international public opinion of the people has shifted more emphatically than ever before.

Throughout 2025, thousands were expelled from Jenin and many homes demolished as the camp faced arguably the worst year in its existence.

In December 2025, Mohammed Bakri died as a result of heart illness.

Last Updated

December 2025

Image sources

Jenin, Jenin (2002) film

Info references

The Electronic Intifada

The Miko Peled Podcast

Al Jazeera

Middle East Eye

Haaertz ‘03 + ‘16

Courthouse News

Palestine Chronicle

Eye on Palestine