Palestine Poster Project

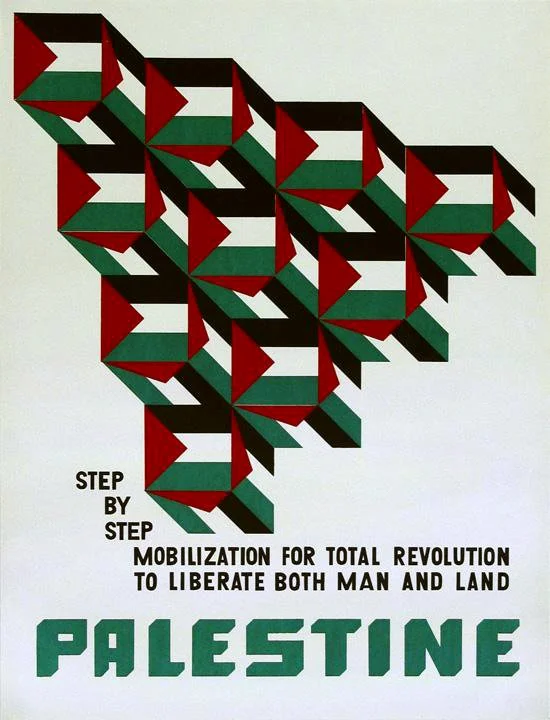

Posters have a long history as one of the most important visual artforms of the Palestinian culture, for many purposes – including arts, politics, and resistance. The ease of which they could be distributed, with accessibility to people in many areas, made them a valuable tool for spreading messages and art.

“The Palestinian poster art surge quickly started in 1968, with the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) adopting the poster as a communication resource and a way to build international solidarity,” says Dan Walsh, Founder of the Palestine Poster Project.

He says it’s the only 20th century political poster art genre to transition into the 21st century, and stay strong in the time of the internet – unlike examples such as revolutionary Cuba and the former Soviet Union.

A former Peace Corps member, Walsh has been collecting posters connected to Palestine for half a century. In 2003, he officially started the website archive. Today, it boosts over 20,000 files – dating from over a century ago to modern day.

The Palestine Poster Project has served as a plentiful and deep archive over the years, as well as being an educational tool for Walsh and American high school teachers to use the art to engage students in a new way with the history of Palestine.

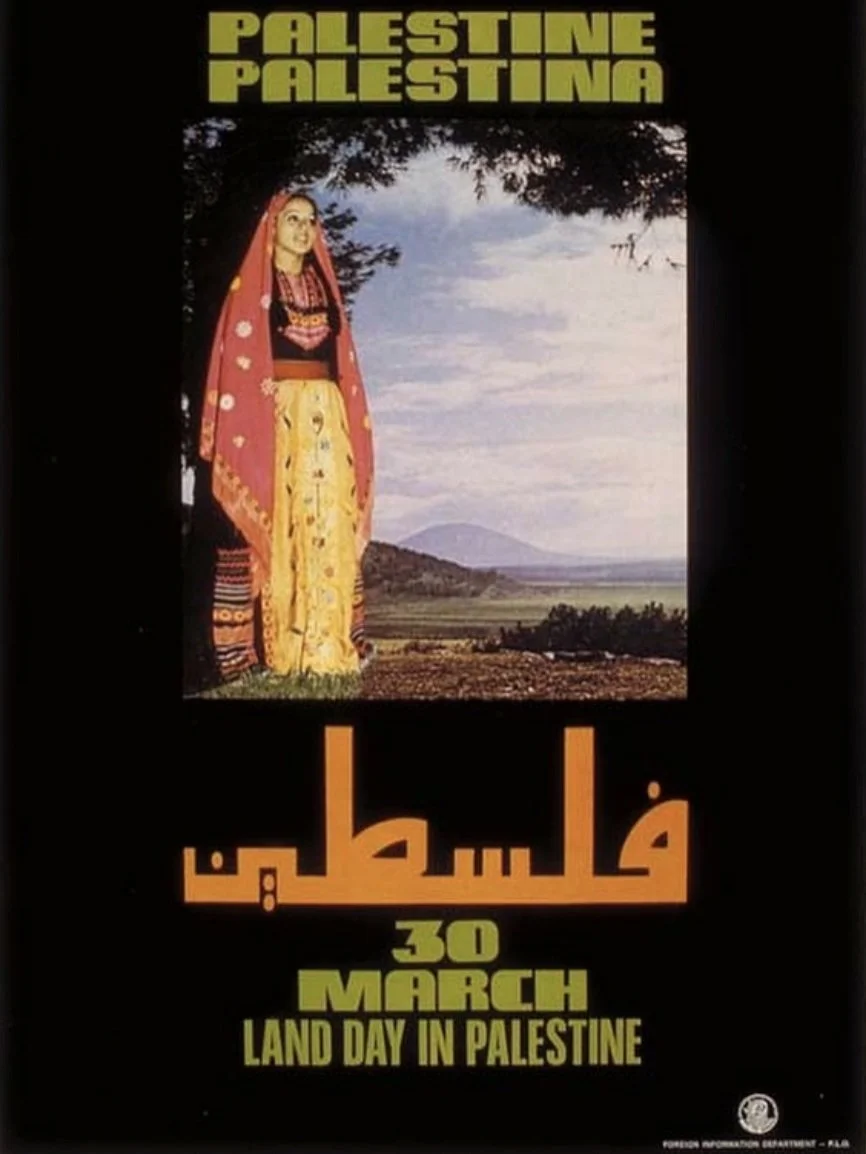

Palestine - Palestina - Filustin. Artist unknown. 1980.

Tree of Palestine. by Ahmad Hegazi. 1985.

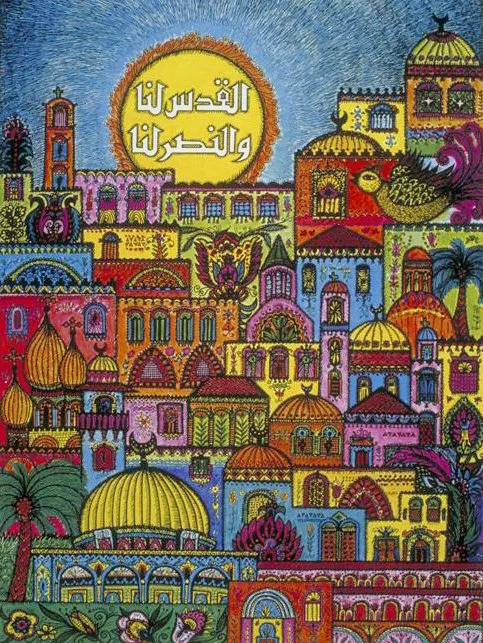

Jerusalem is Ours, Victory is Ours. by Burhan Karkoutly. 1979.

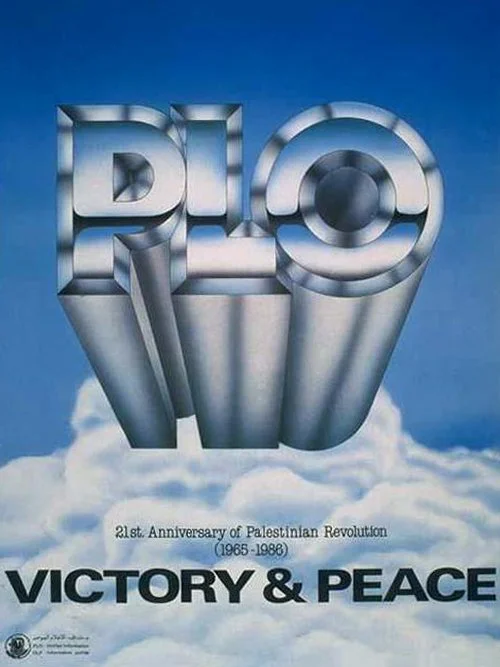

Peace and Victory. Artist unknown. 1986.

Journee De Solidarite Avec Les Enfants Palestiniens (International Day of Solidarity with the children of Palestine). by Fadwa Abdel Rahman. 1985.

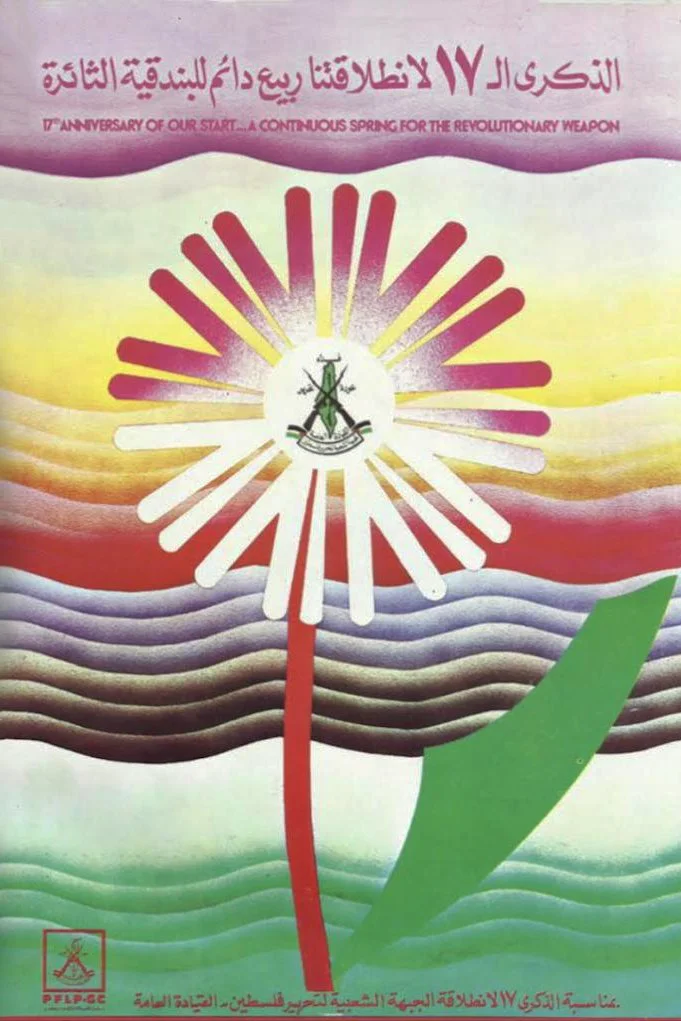

17th Anniversary of the Palestinian Revolution. by Kamal Nicola. 1983.

Dan Walsh was a Peace Corps volunteer in Morocco for a couple of years in the mid 1970s, working as an industrial arts instructor.

He was learning Arabic, the local language, from a tutor at the time. Walsh did his best to translate his lessons from English using this growing knowledge.

In the process of further improving his Arabic, his tutor suggested he translate posters. During this practice, he saw posters that were mostly about local events, ads, or movie posters.

Walsh had been stationed in Marrakaech, but at one point he went to visit Rabat, Morocco’s capital. While there, he saw a poster on a building with a word he didn’t recognize. A man stepped outside who saw his confusion and told him the word was “Palestine.”

This person who Walsh met turned out to be a representative of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), and he was invited inside the office for tea and a conversation about art and politics.

Before he left, the man showed Walsh a closet full of Palestine posters and was told he could take however many as he liked. He took 25 and was told to return any time, as new posters were always coming in.

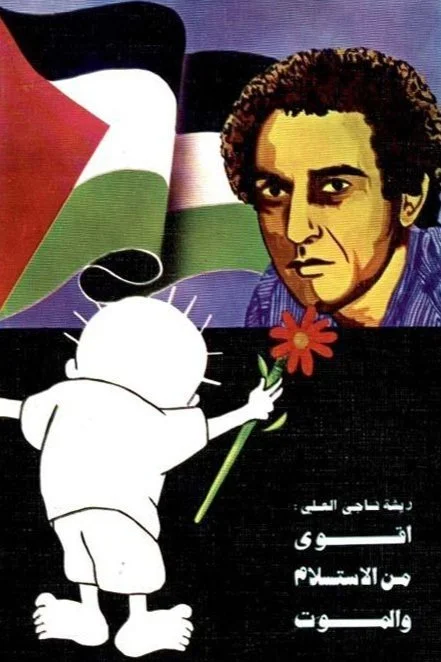

The Pen of Naji Al Ali. by Ghazi Inaim. 1987.

Additional note: "Handala, also Handhala, Hanzala or Hanthala, is a prominent national symbol and personification of the Palestinian people. The character was created in 1969 by political cartoonist Naji al-Ali."

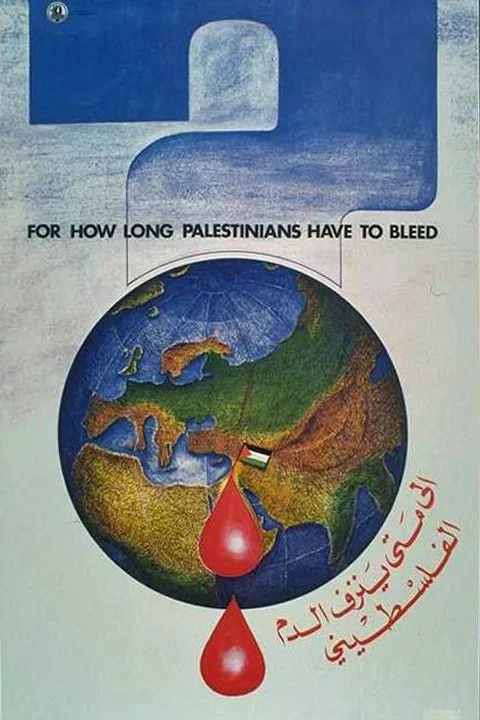

For How Long Palestinians Have To Bleed? Artist unknown. 1985.

In the Occupied Homeland. by Khair Allah Sheik Saleem. 1985.

Al Quds Est Dans Mon Coeur (Al Quds is in my heart). by Ismail Shammout. 1979.

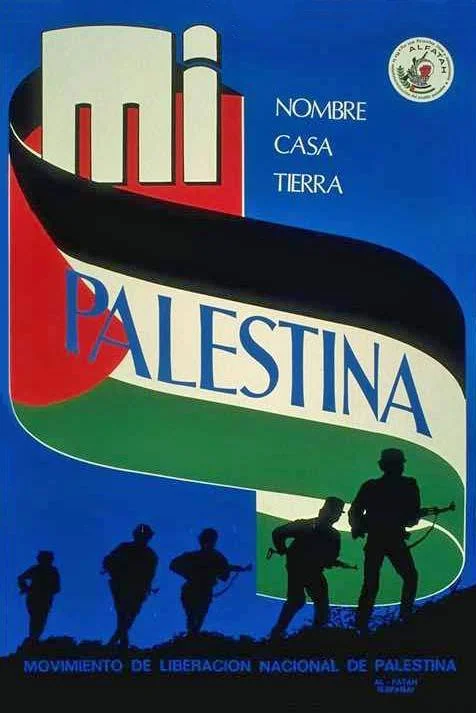

Mi Palestina. Artist unknown, published in Spain. 1986.

Continuous Spring. Artist unknown. 1985.

Embrace the Sky. by Marc Rudin. 1989.

Palestine Will Win. by Marc Rudin. 1985.

Fighters. by Emad Abdel Wahhab. 1984.

Additional note: “The uppermost woman depicted is thought to be Shadia Abu Ghazaleh; the second woman from top is Dalal Moghrabi; the third woman from top is Taghrid al Batmeh; the portrait at the bottom is possibly that of Rajaa Abu ‘Ammash'.”

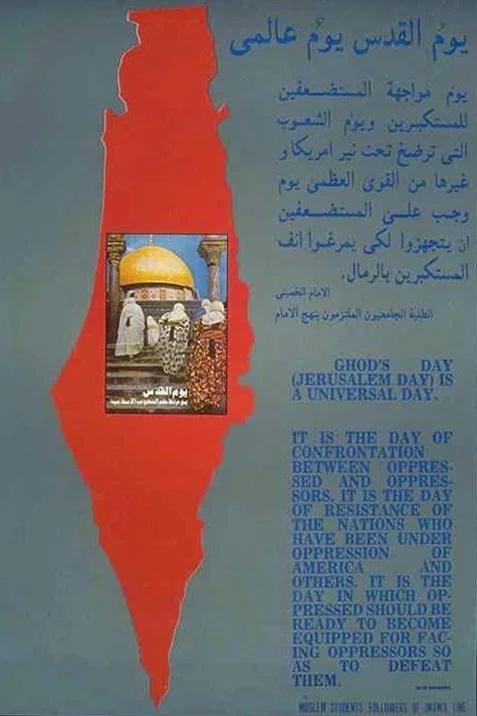

Jerusalem Day Is A Universal Day. Artist unknown. 1979.

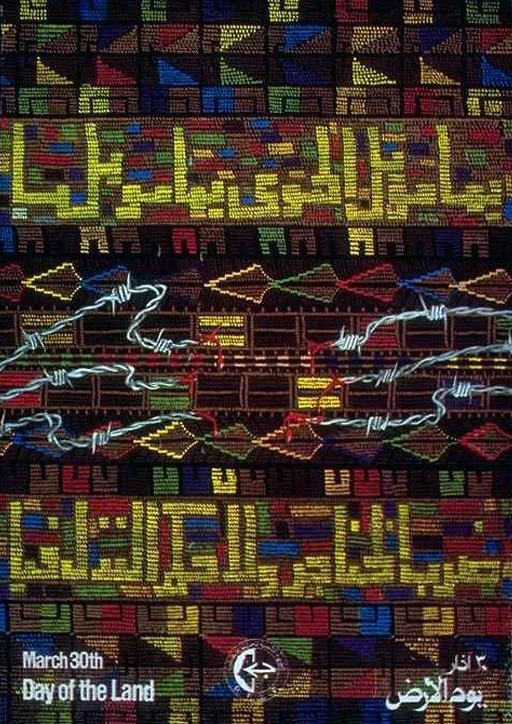

Land Day - PPSF. Artist Unknown. 1988.

29 Tashreen Thani (November 29, International Solidarity with Palestinian People). by Muwaffaq Mattar. 1985.

The Moroccan PLO representative also wrote a letter of introduction for Walsh after their meeting, opening doors for him to visit their offices in other countries.

During his time in the Peace Corps, including a backpacking trip between his two years of service, Walsh embraced the opportunity. He visited PLO offices in France, Spain, Holland, Italy, Germany, and the UK. At each stop, he would add to his poster collection.

By the time he came back from his service in 1976, he had 200 Palestine posters across a variety of syles and languages.

Upon returning home, he went to Ohio State University to get an industrial technology degree, where he also then minored in Arabic and contemporary Middle East studies.

During this time, Walsh continued to collect posters in the mail, at conferences, or through personal contacts.

After moving to Washington DC upon graduating in 1979 he became active in returned Peace Corp groups with the focus on a goal of helping Americans understand other cultures.

During this time, he was often asked to exhibit some of his posters and speak about them. However, due to the logistics, he could only afford to show a few at a time at any given event.

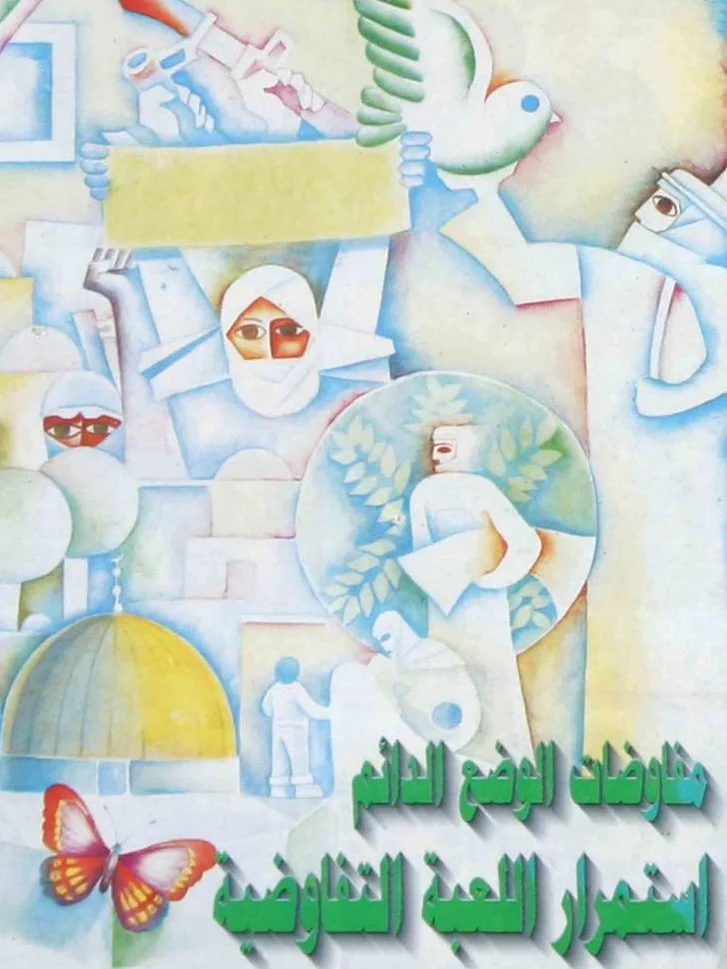

Negotiating Game. Artist unknown. 1975.

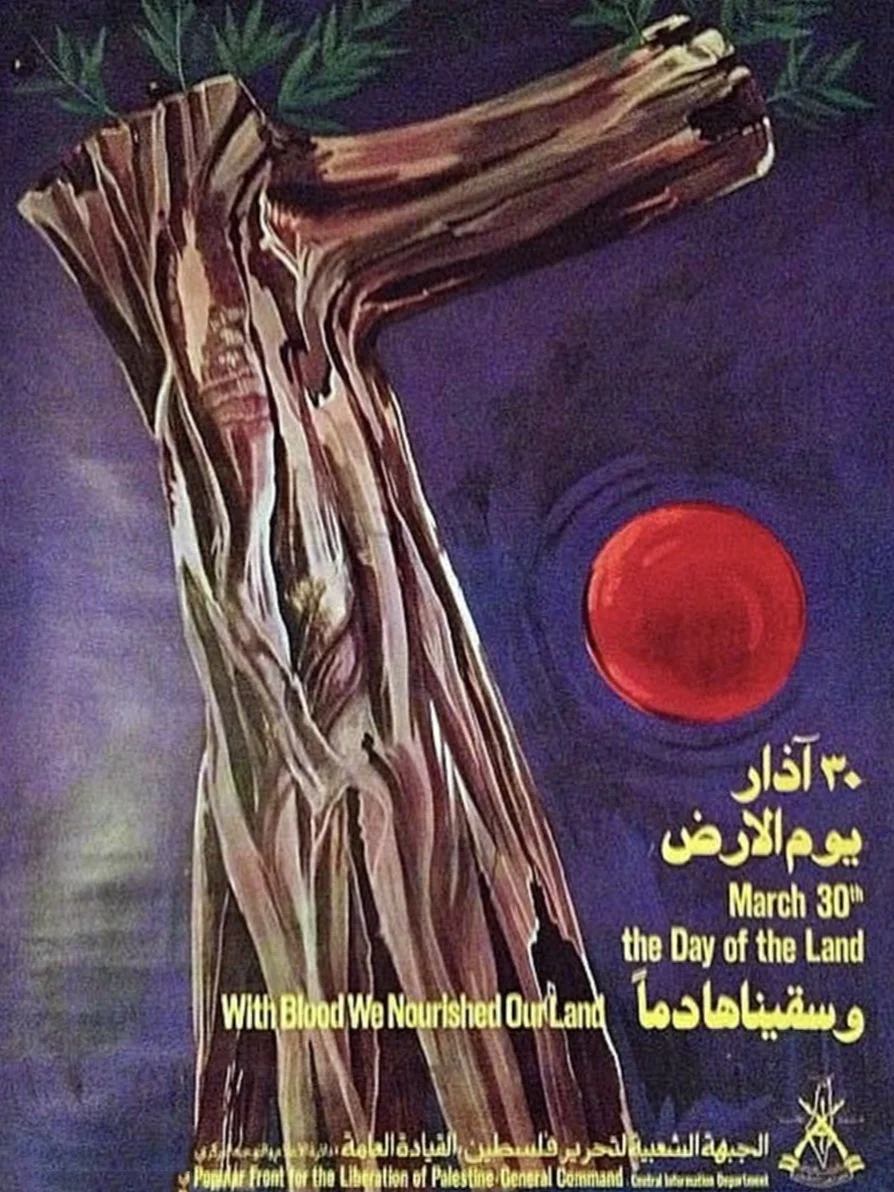

We Nourished Our Land. by Abu Manu. 1985.

Second General Exhibition - Union of Palestinian Artists. by Ismail Shammout. 1979.

Al Najah National University - Students Union. Artist unknown. 1985.

Nazareth, Palestine. by Ismail Shammout featuring an 1875 drawing David Roberts. 1983.

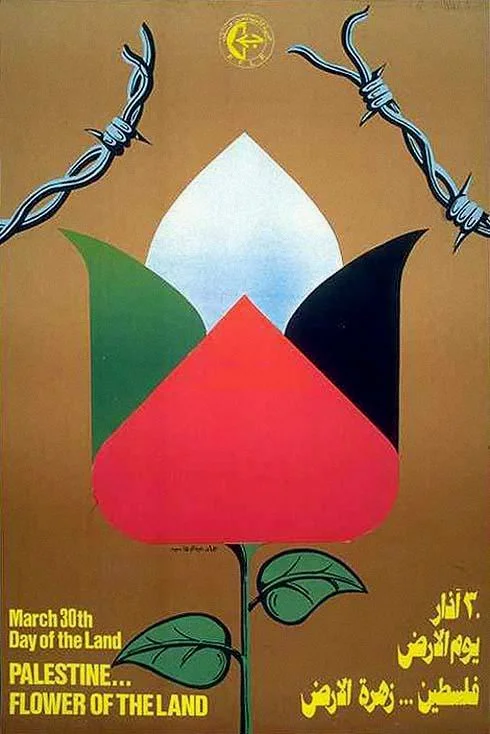

Flower of the Land. Emad Abdel Wahhab. 1992.

After a few years, Walsh’s work got the attention of the American-Palestine Education Foundation (APEF).

One of the people on their board was Edward Said, the late Palestinian academic and philosopher. Said and the APEF wanted to support his work, so they awarded him a small grant in 1982 to cover the costs of photographing 300 of the posters and turning them into a portable slide show.

This changed the way Walsh saw the possibilities of sharing and showcasing the collection, including the much wider access the posters received as a result.

At this time, Walsh also started his own design company, Liberation Graphics, and worked as an art director. Over that time, he connected to collect more posters.

In 1999, he received another grant for the project – this time from the Ruth Mott Foundation, who underwrote the costs converting his collection – 2,000 original posters at the time – into digital files.

In 2003, he started a website and called it The Palestine Poster Project. Since then, he has continued to build it as an archive and educational resource.

While a slideshow previously had made these works more accessible, the Internet took that to a whole new level. The website was a game-changer for the intiative.

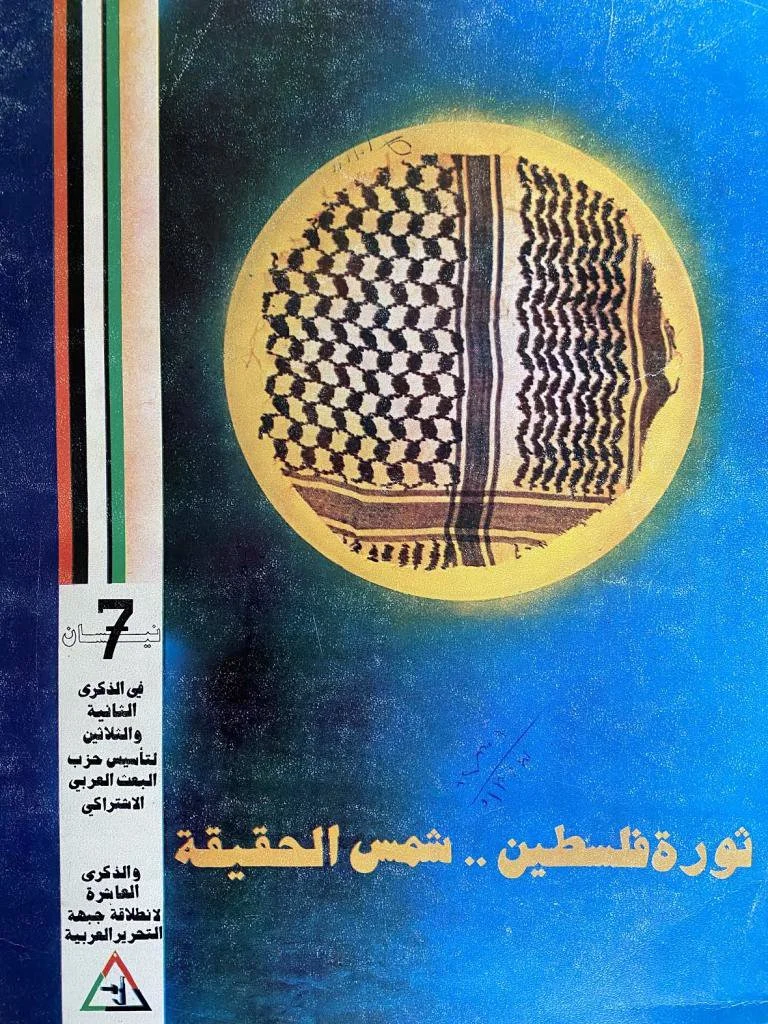

Sun of Truth. by Hassib Al Jassem. 1979.

Woe to Love. Artist unknown. 1980.

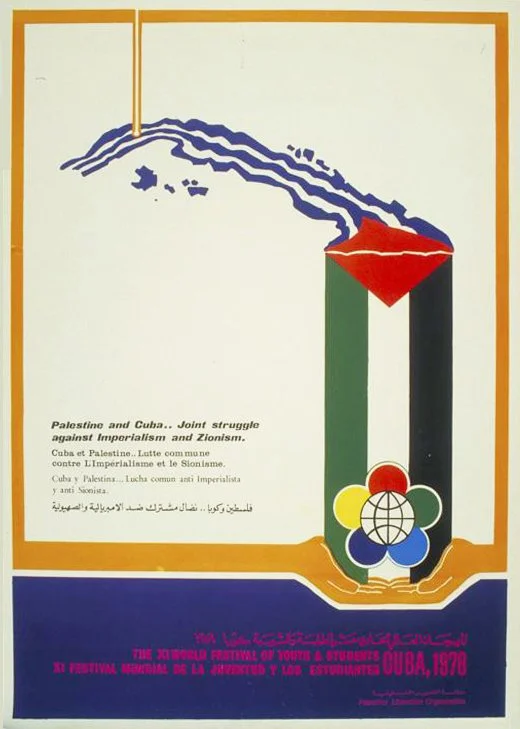

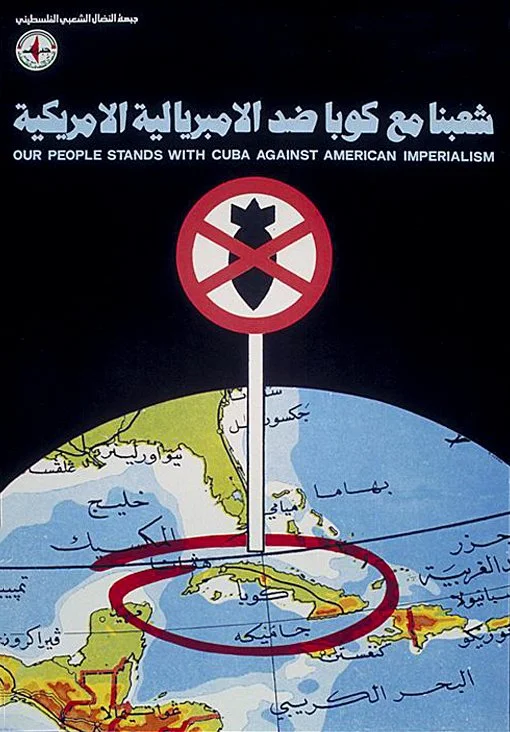

Joint Struggle (with Cuba). Artist unknown. 1978.

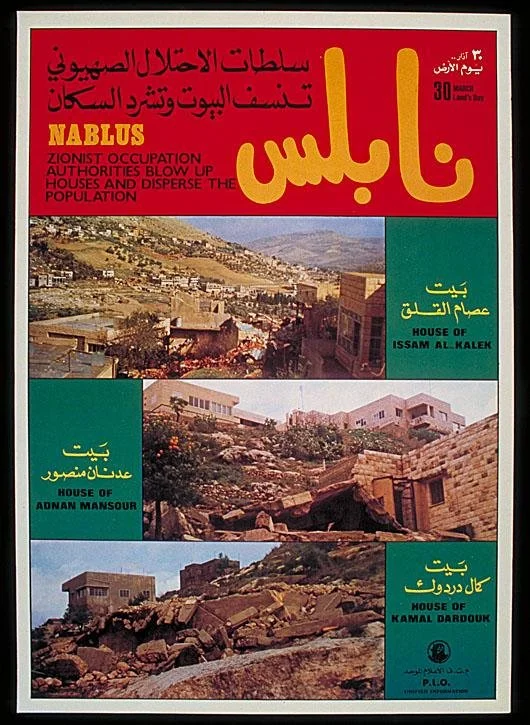

Nablus - Zionist Occupation Authorities. Artist unknown. 1980.

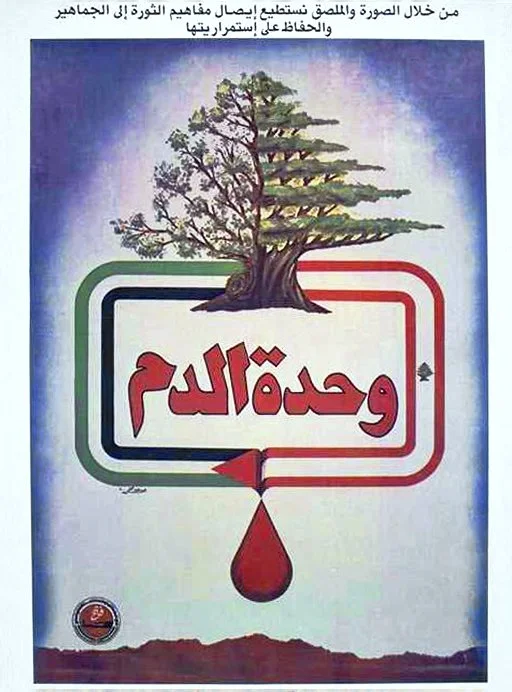

Unity of Blood. by Yusuf Hammou. 1985.

Return Way To Palestine (for PPSF). by Ibraheem Musa. 1988.

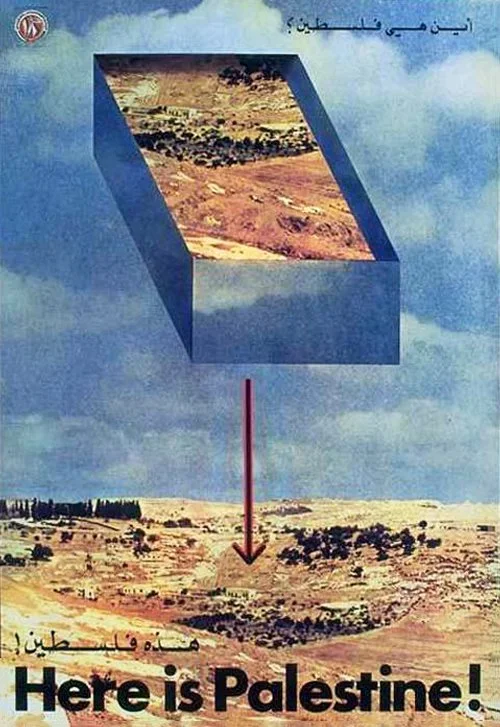

Here is Palestine! - Artist unknown. 1983.

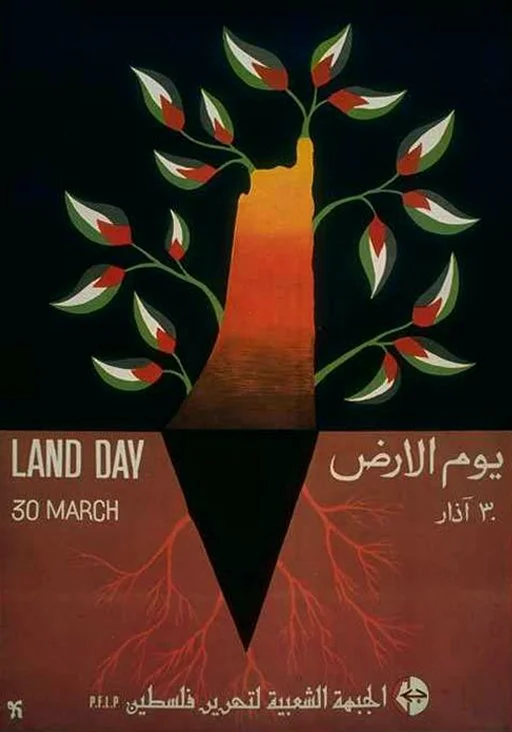

Land Day (for PFLP). by Kamal Nicola. 1981.

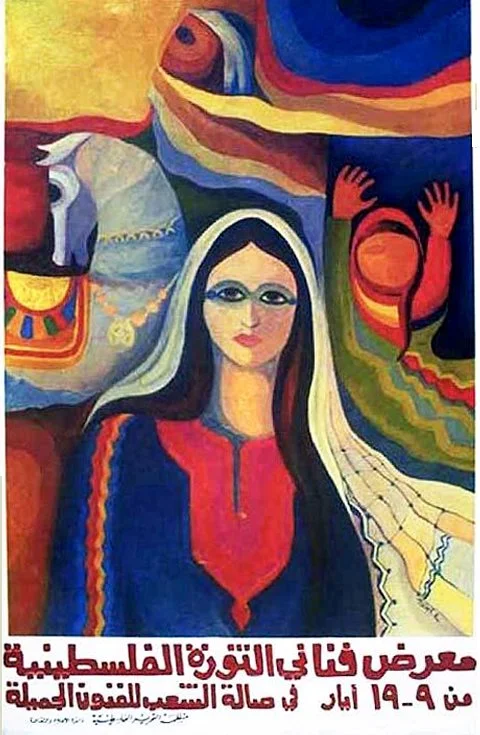

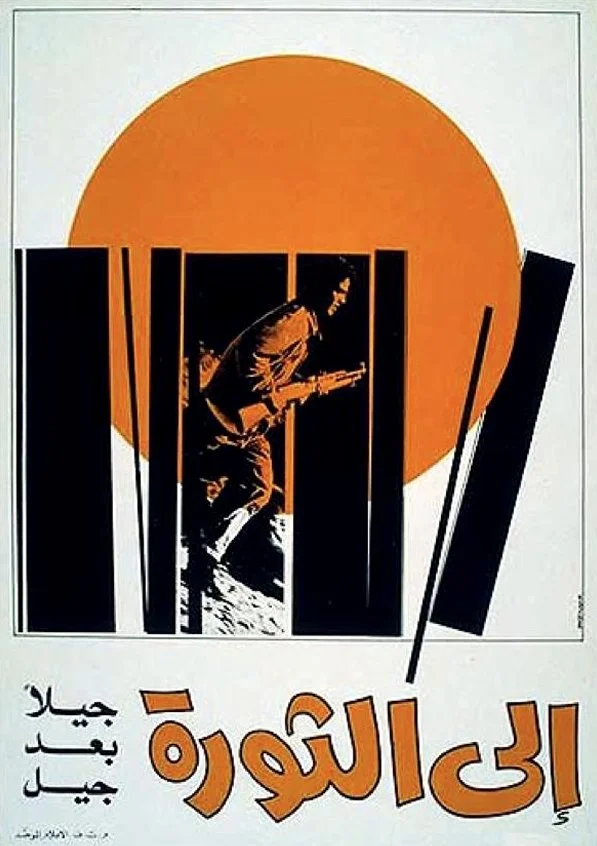

Palestinian Revolution. by Abd Almouty Abozaid. 1981.

After having the website up and running, and continuing to add to it, Walsh also wanted to find other ways to use the posters as a tool for education – particularly in American high schools.

On his website, in addition to the Palestinian posters, Walsh also includes a collection of Zionist posters from the early 20th century that show the history of how they presented messaging leading up to the 1948 Nakba.

These posters encouraged traveling to Palestine, immigrating there, investing in the country, and so forth. Then, in 1948, the same printer changed their poster from Visit Palestine to Visit Israel within a month.

This comes into play with the educational approach as it’s a topic almost entirely absent from school curriculum when discussing the history of Palestine. During one lecture, Walsh noted:

“There is nothing that actually follows an arc from Theodor Herzl and the first Zionist Congress in Basel (Switzerland) in 1897, where Zionism actually launched itself onto the world stage. Students are still pretty much befuddled and the subject of Palestinian nationalism and political Zionism continues to be almost off limits.”

Walsh looked at the textbooks of high schools in his local DMV area (DC / Maryland / Virginia) of the US and found that all the textbooks were very limited in their teachings about Palestine.

Walsh wanted to provide a way for students to be able to learn about the history in a more complete way, and have teachers be able to use the posters as an access point to teach about it.

While presenting posters to students, he would ask them how they interpreted it and open up a discussion. Along with the regular teacher, they were there to help facilitate that dialogue and share any information.

“The students are asking questions and they begin to talk and argue and debate the issues among themselves. By the time of a half an hour into the class, we've gone through maybe six or eight posters. And generally I learned something in the process.

That changes that dynamic because we actually then take the classroom of American high school students and – probably for the first time in their lives – they're talking about Palestinian nationalism. They're talking about Pan-Arabism. They're talking about antisemitism. They're asking questions about Zionism with Theodor Herzl.

So it changes the dynamic because people are actually practicing for civic power. So I think that's one of the things that the Palestine poster does uniquely. It does it better – or differently, or maybe in complete contravention – to books and lesson plans and literature and lectures.”

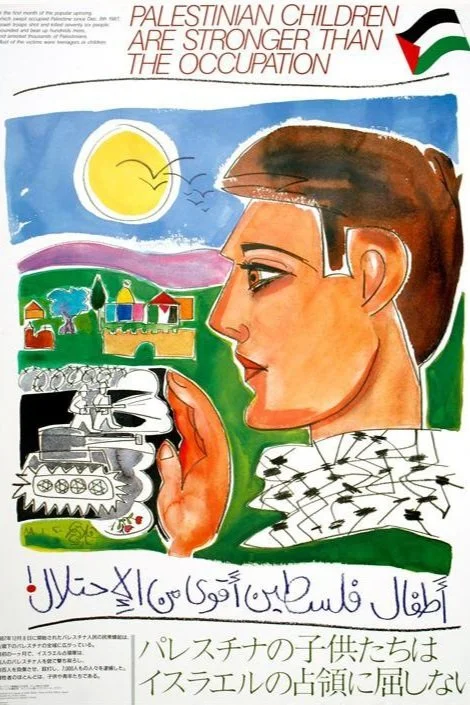

Stronger Than the Occupation by Vladimir Tamari. 1988.

Land Day - Yom al Ard (On The Other Hand). by Abdel Rahman Al Muzain. 1983.

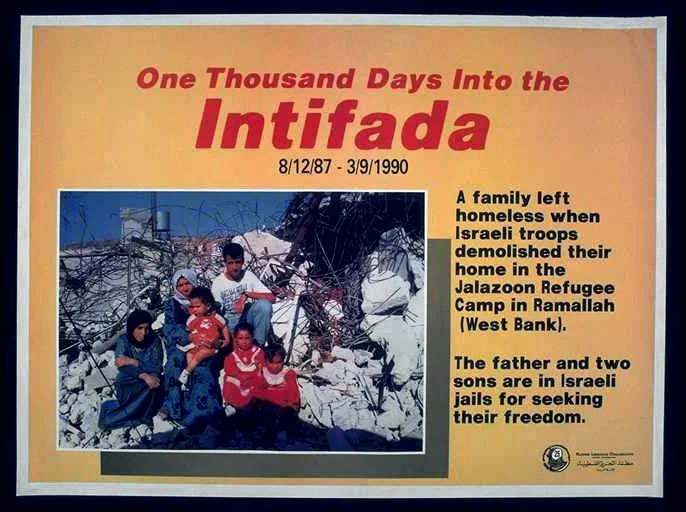

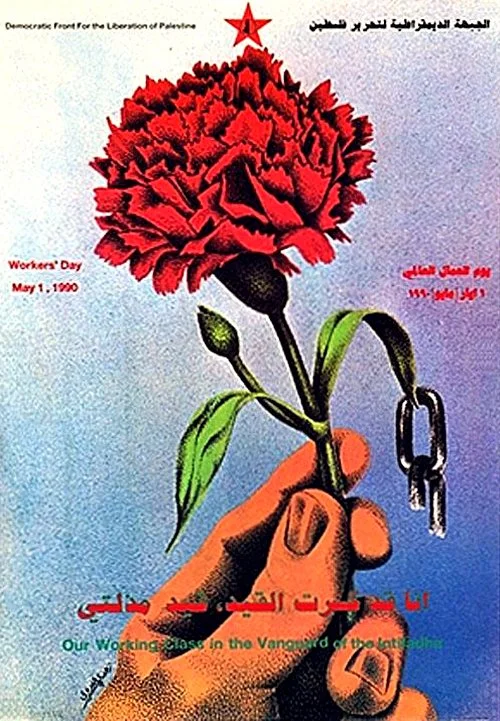

2nd Anniversary of the Intifada. by Zuhdi Al-Adawi. 1990.

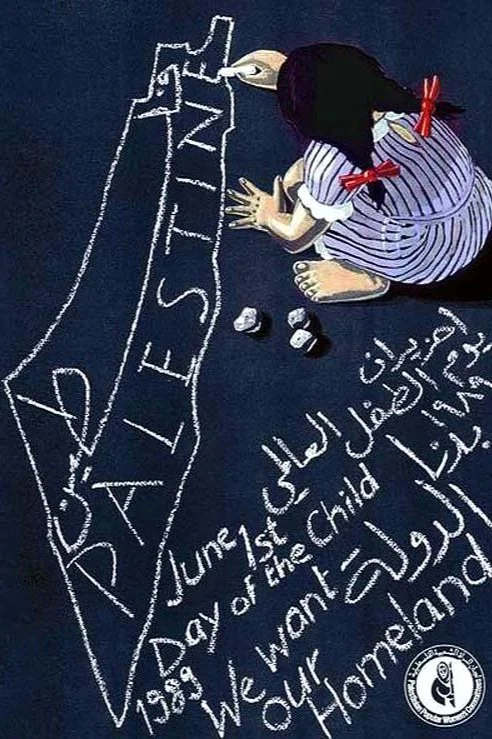

We Want Our Homeland. by Marc Rudin. 1989.

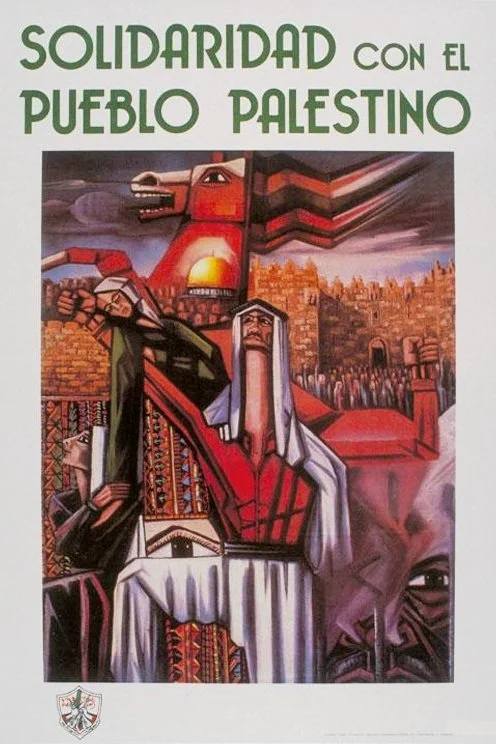

El Pueblo Palestino. by Fathi Ghabin. Originally published in Spain. 1987.

State of Palestine. by Kamal Kaabar. 1989.

Seventh of Kanun al Thani (January). by Kamal Kaabar. 1980.

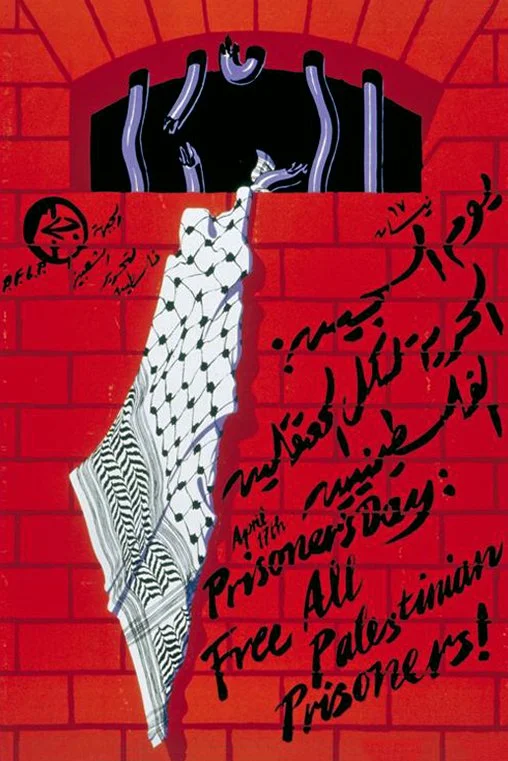

Free All (Prisoner's Day). by Marc Rudin. 1990.

Stronger Than Siege. by Zuhdi Al-Adawi. 1987.

Jerusalem - Capital of the State of Palestine. Artist unknown. 1989.

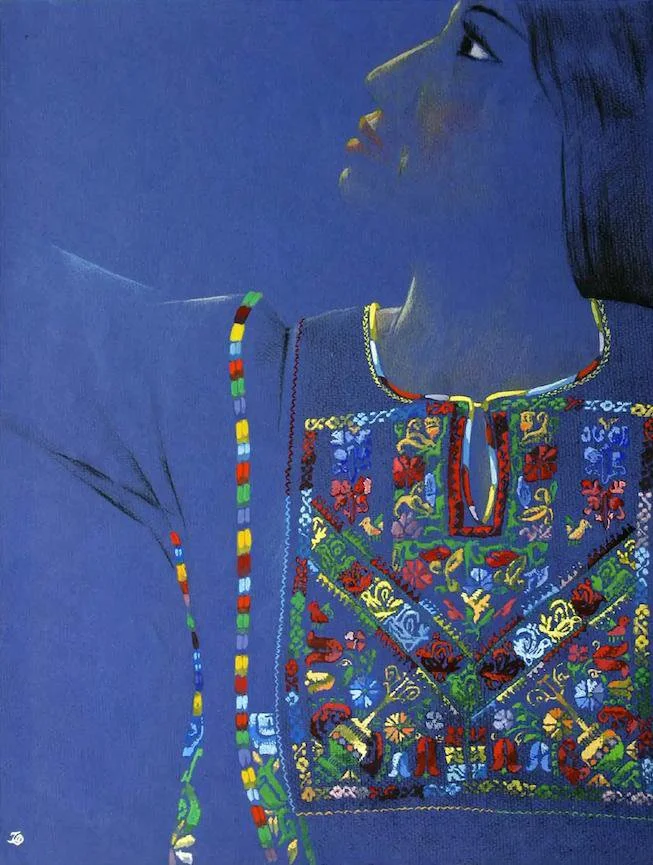

Folklore Day. Artist unknown. 1985. International Palestinian Folklore Day

Continuous Revolution In the Occupied Homeland. by Abd Almouty Abozaid. 1982.

Walsh still updates The Palestine Poster Project site regularly.

There are plenty of posters being made currently, though most of them now come from international artists in solidarity with the cause.

A platform who shares these modern day versions is Flyers for Falastin – which Walsh archives a collection of on his website, too.

“Prior to the maturation of the Internet in the early 1990’s, poster publishing was restricted to those who could underwrite the significant recurring costs involved in design, mass printing, and distribution,” Walsh says. “Thus most titles were institutionally published and disseminated from a single geographic point.”

Posters have seen a particular resurgence in the midst of the ongoing Gaza genocide – calling attention to the atrocities, calling for a Free Palestine, calling for an end to the occupation.

The increased amount of protests during this time has also led to a large amount of posters made for organizing and digital posting purposes. The poster form nowadays more rarely gets physically printed and put up in public, but it still does happen. Yet it is safe to say that the majority of posters are now digitally-made and digitally-distributed.

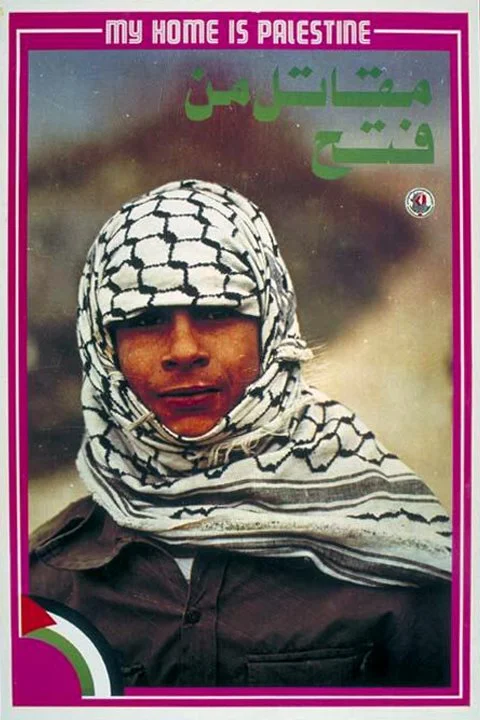

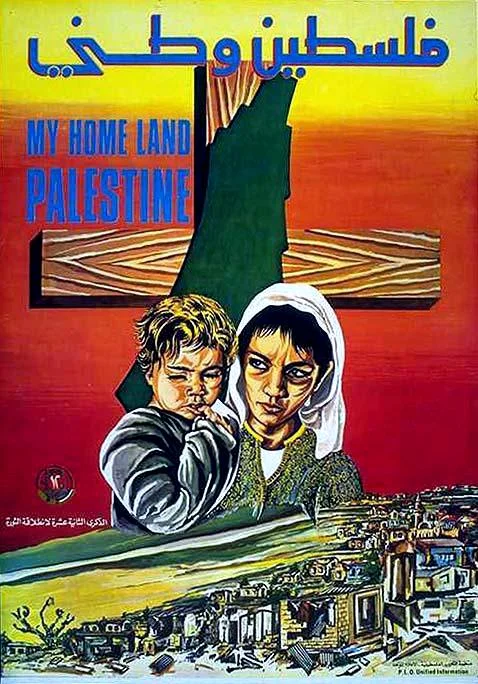

My Home is Palestine. Artist unknown. 1985.

Towards. by Hassib Al Jassem. 1984.

Our People Are With Cuba. by Mahmud Dawirji. 1980.

Palestine Needs Arab Solidarity. by Hosni Radwan. 1980.

The Jalazoon Refugee Camp. Artist unknown. 1990.

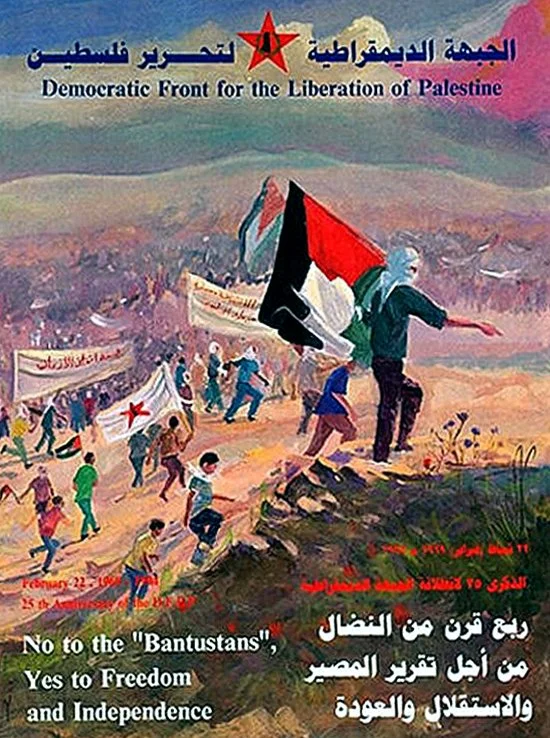

No To the 'Bantustans'. by Jamal Al Abtah. 1993.

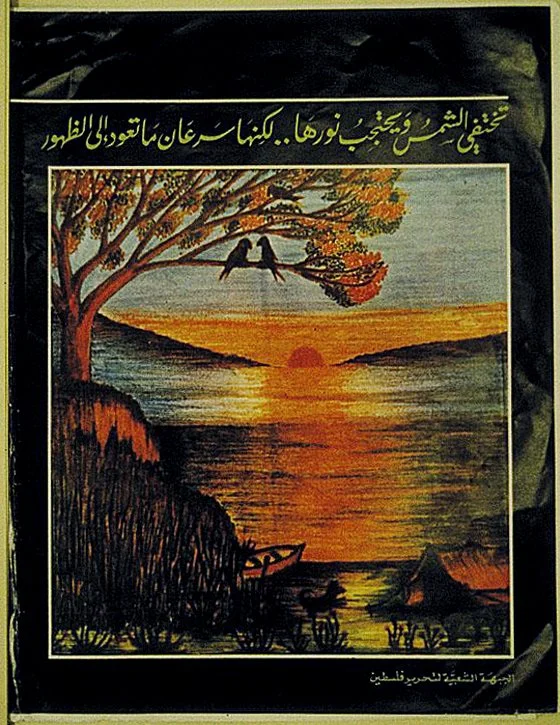

The Sun Disappears. by Hatem Ghannam. 1980.

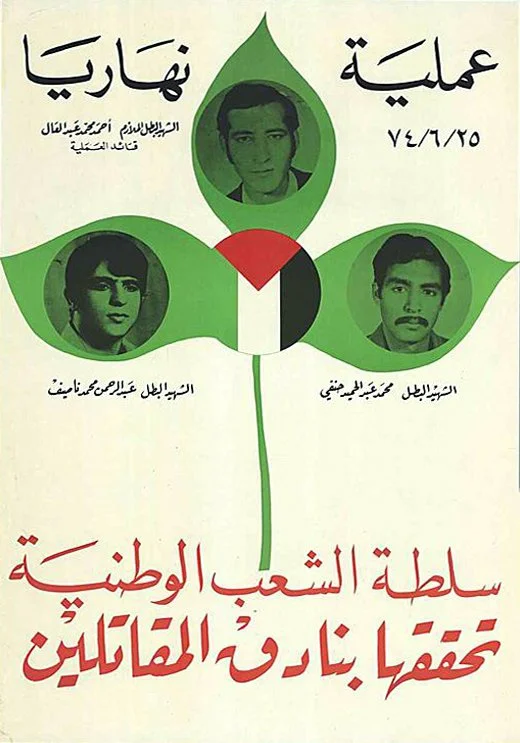

Operation Naharia. Artist unknown. 1974.

Together On the Path of Struggle. by Gneerla Union of Palestinian Women. 1982.

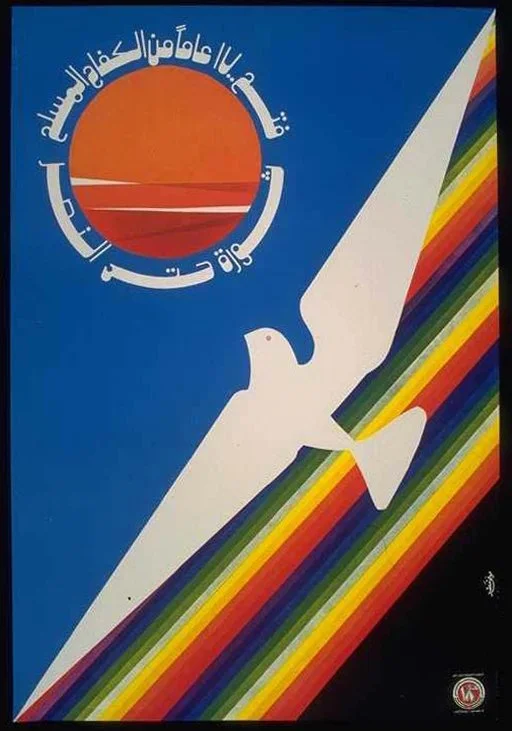

Strive With Sincerity. Artist unknown. 1980.

Additional:

The Height of the Palestine Poster in the 20th Century

Since the designs on this specific page focuses more at the height of the Palestinian poster during the 1970s and 80s, it’s worth sharing some notes from Sascha Manya Crasnow.

Crasnow – who is now a Lecturer of Islamic Arts – wrote about the historical context of that peak poster era in her 2018 dissertation, The Next Generation.

For her research, Crasnow had spoken with both Dan Walsh and another Palestine Poster Project contributor, Rochelle Davis, to better understand the archive and history.

When the PLO was first founded in the summer of 1964, art was soon brought into the mix as a device of resistance. The Arts & Culture department started quickly, in 1965. It was directed by artist Ismail Shammout – alongside his wife, Tamam Al-Akhal – both of whom had been displaced from Palestine to Beirut.

“This acknowledgement of the potential of art to serve in the revolutionary cause was perhaps most apparent in the mass production of poster art at the time.”

Posters were used to spread the messages and ideology of the PLO in trying to further mobilize Palestinians around their shared cause and struggle and often went up on city walls, including in nearby neighboring countries where many Palestinians had been displaced.

This was also important since Palestinians had no way to organize or source arts education and production, so the PLO was able to provide that foundation for many artists – including Sliman Mansour, for example, who drew posters often himself.

It also provided a space for other artists working for the PLO to learn and develop.

Crasnow notes that the posters at this time were mostly produced in a singular location, such as the PLO offices in Beirut, with prints then distributed to other countries.

Core of the World. by Abu Manu. 1987.

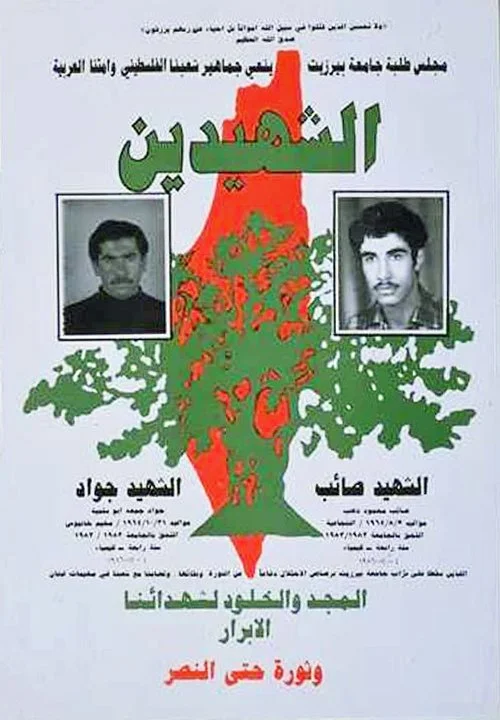

Two Martyrs. Artist unknown. 1983.

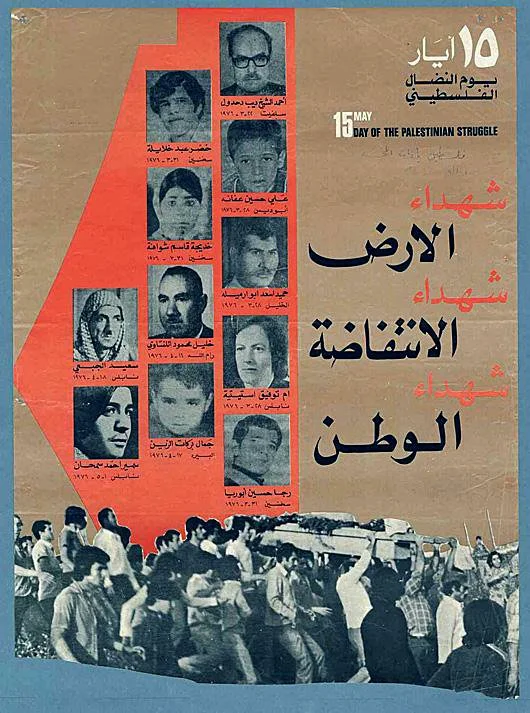

Land - Intifada - Nation. Artist unknown. 1976.

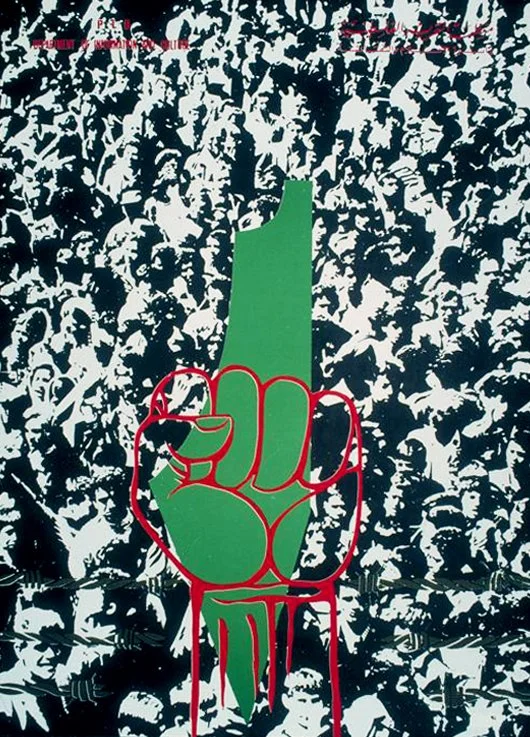

Vanguard of the Intifada. by Zuhdi El Adawi. 1990.

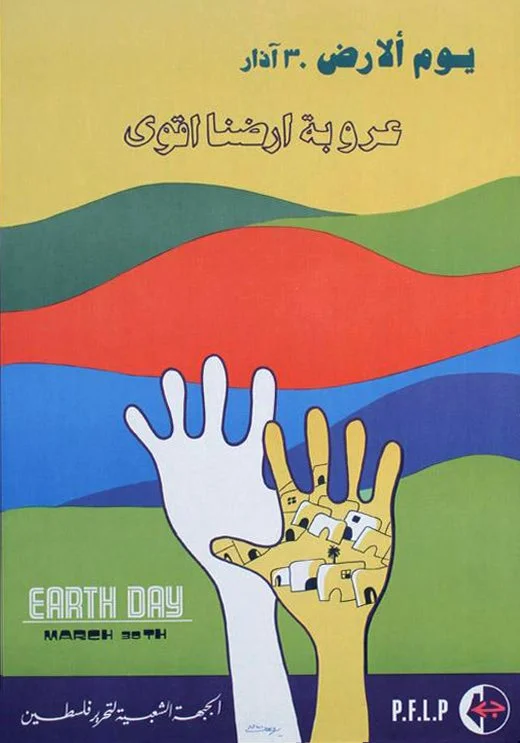

Earth Day (for PFLP). by Yusuf Al Nasser. 1976.

Naji Al Ali Drew for Palestine. by Marc Rudin / Jihad Mansour. 1987

Mass Resistance, Mass Determination. by Ghazi Inaim. 1985.

War To Free the People. by Ghazi Inaim. 1990.

Fatah at 25. Artist unknown. 1990.

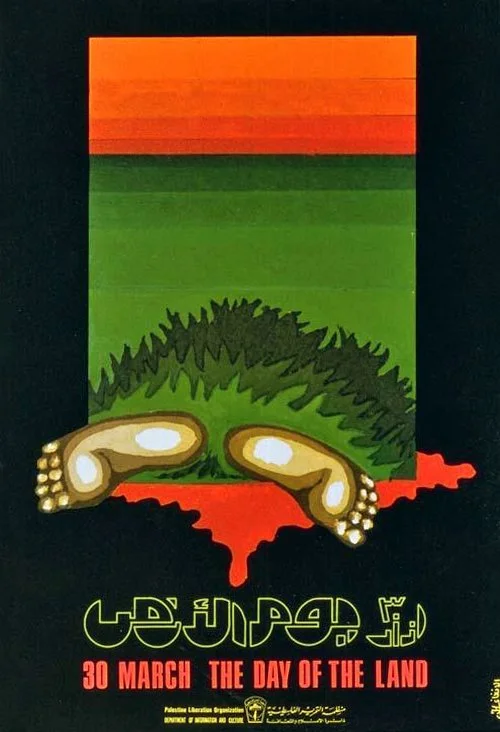

The Day of the Land. by Jamal Al Afghani. 1980.

Our Struggles Continue. Artist unknown. 1985.

17 Years of Armed Struggle. by Muwaffaq Mattar. 1983.

International solidarity had been an important part of the posters’ messaging and encouragement as well, and that manifested in multiple ways.

When the Palestinian poster genre was starting to get its feet wet in the 1960s, it also exchanged ideas with other countries at the inaugural OSPAAAL conference in 1966. Crasnow writes:

“The posters created by Palestinian artists, much like their fine art work, also served to create a unified Palestinian identity for the purpose of rising together in resistance.

However, these works varied in style from the fine arts production of the time by these artists, having been influenced particularly by the graphic works coming out of Cuba and Latin America.

A 1967 poster by Cuban painter Tony Evora, connected to OSPAAL

The poster by Tony Evora was also printed in English (above) and in French

This influence came about through the Tricontinental Conference in Havana and formation of the OSPAAAL (Organization of Solidarity of the People of Asia, Africa, & Latin America) in 1966, at which delegates from the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) were present.

This conference brought together representatives from countries across Asia, Africa, and Latin America with leftist, anti-imperialist views to collaborate, discuss means of solidarity, and continue to establish the presence of a network in opposition to those colonial and neo-colonial powers that dominate on the global scene. The influence of OSPAAAL can be seen in both the style and content of the imagery prominent in Palestinian posters of the time.”

This international connection also meant that some posters were printed in multiple languages. Sometimes this was in separately-designed versions, and sometimes it was on one poster if there was a short phrase that could be repeated.

A 1980 poster, Frente Polisario (artist unknown), for OSPAAL – with languages of Spanish, English, French, and Arabic

These posters were often shipped to Europe, Asia, Africa, or Latin America – in addition to Palestine itself and Palestinian refugee camps in neighboring countries.

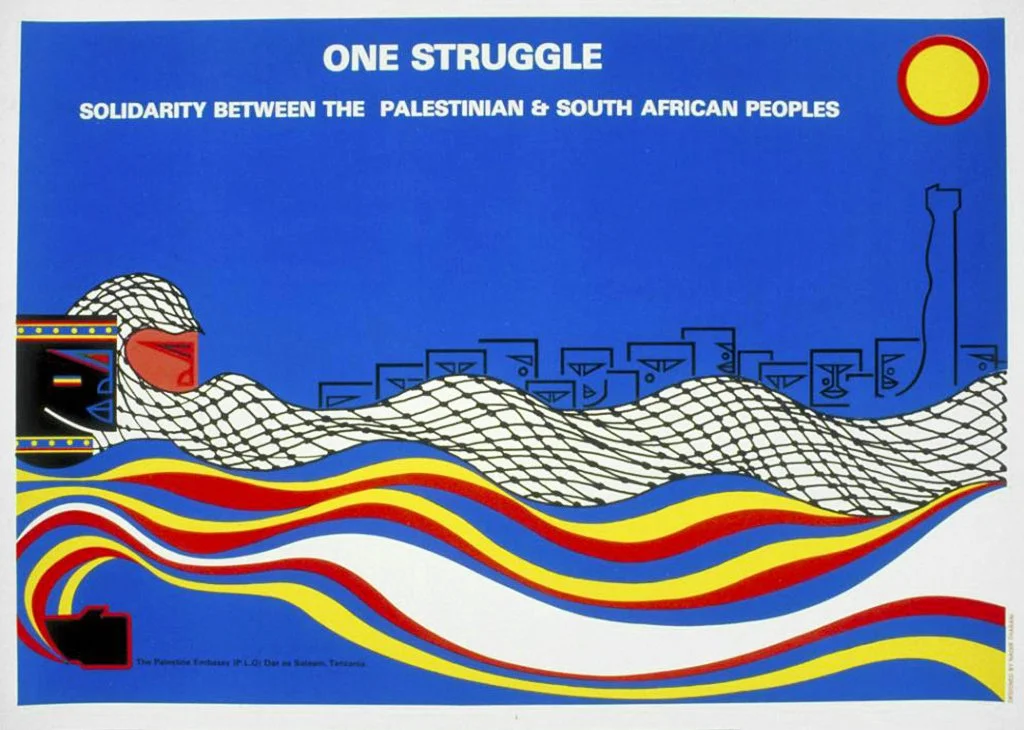

One Struggle. by Nadir Tharani. 1978.

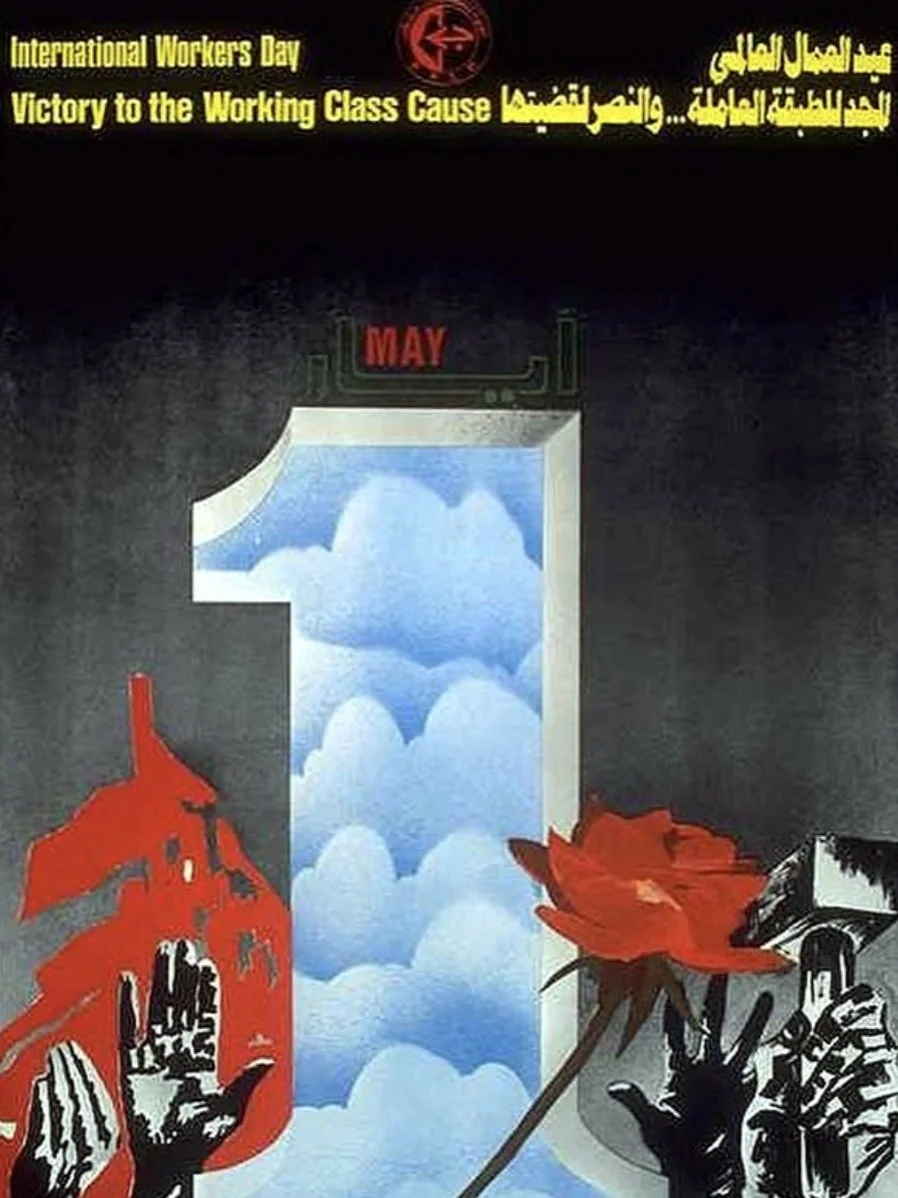

Working Class Cause. by Yehia Al Sheik. 1985.

Palestine of Tomorrow. by Abd Almouty Abozaid. 1989.

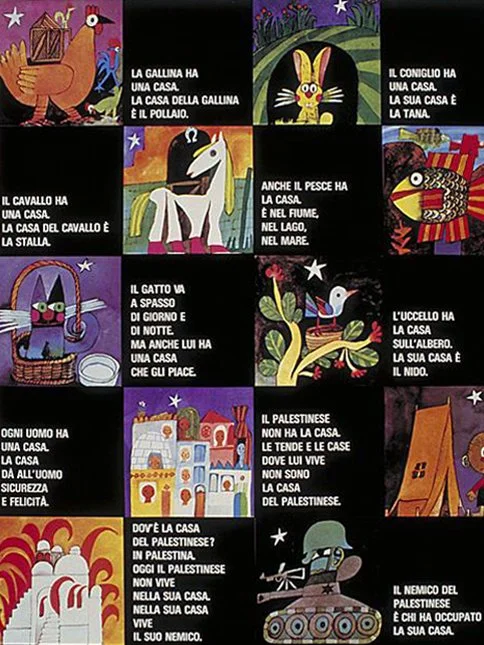

La Casa. by Mohieddin El Labbad. 1979.

Detainees in "Israeli" Prisons. by Hassib Al Jassem. 1980.

No Voice Stronger Than the Voice of the Intifada. Artist unknown. 1988.

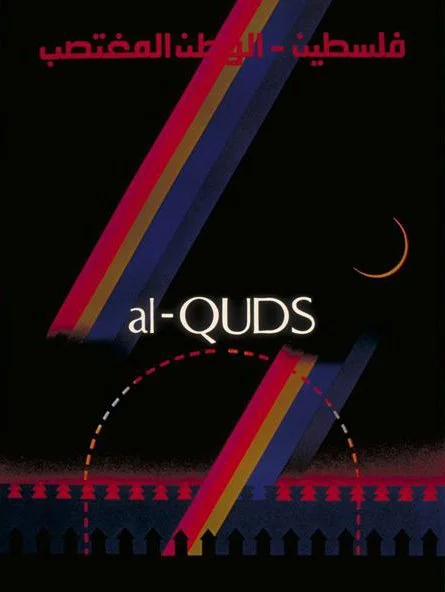

Palestine: A Homeland Denied. by Mohammed Melehi. 1979.

Resists - Lives - Fights. Artist unknown. 1977.

The 1960s had set up the Palestine poster for success. In the 1970s and 1980s, it was full steam ahead.

This included some contributions from Palestinian artists like Sliman Mansour, Fathi Ghaben, Samia Halaby, and Zuhdie Al Adawi to name a few.

Sometimes posters would utilize existing paintings of these artists to be distributed through this replicable form, allowing them to find a mass audience at a cheap cost of printing. It also allowed Palestinians, in particular, to have these pieces of art in their homes or refugee camps.

Samia Halaby poster from 1970

Sliman Mansour poster from 1987

Other international artists who believed in the Palestinian cause also participated, such as Switzerland-born artist Marc Rudin who had been very politically active since the 1960s. After first getting connected with Palestinians in the mid-1970s, he started designing posters in support.

Rudin then worked as a designer for the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) for over a decade from 1979-1991 under the name "Jihad Mansour" and even fought in the field for the Palestinian resistance in Beirut.

Marc Rudin / “Jihad Mansour” poster from 1980

However, this peak era of posters slowed down with the signing of the Oslo accords in 1993.

On one hand, there was a new temporary hope for some that progress was being made for the long-awaited establishment of a Palestinian independent state.

The PLO itself had been in decline. They had lost power after being forced out of Beirut during Israeli Occupation Forces’ 1982 invasion of Lebanon. The Oslo process exacerbated this further with the establishment of the Palestinian Authority – led by Yasser Arafat and the Fatah party – further decreasing the PLO’s role.

“Both the organization and its messages, as expressed through poster art, no longer seemed relevant after Oslo,” writes Crasnow. She also notes the role of technology in the decrease of posters being made during the latter 1990s period.

“Additionally, the post-Oslo shifts from grassroots activism to a proliferation of NGOs virtually extinguished local organizing and activism in which poster production proliferated in favor of funding for specific program-based work and grant-writing backed by international funding which did not take poster production as its focus.

This shift in focus and funding among organizations was coupled with the increasing costs to mass-produce posters as compared with the relative ease of mass distribution of imagery that the rise of the Internet provided.”

As a result, the posters no longer served as the primary vehicle for articulating the Palestinian national identity and mission in visual art and culture.

That’s not to say there weren’t uses of posters over the years – such as martyr posters in the early 2000s.

With the range of media and tools available these days, one mightsay that posters will never have quite the same power, need, and significance than they did during the 1970s and 80s.

However, the Gaza genocide and use of social media has resulted in a new surge of digital posters.

The massive amount of poster art produced since the 1960s creates a vast legacy of visual art, which has been kept alive through the work of the Palestine Poster Project and other efforts over the years to document and archive these materials.

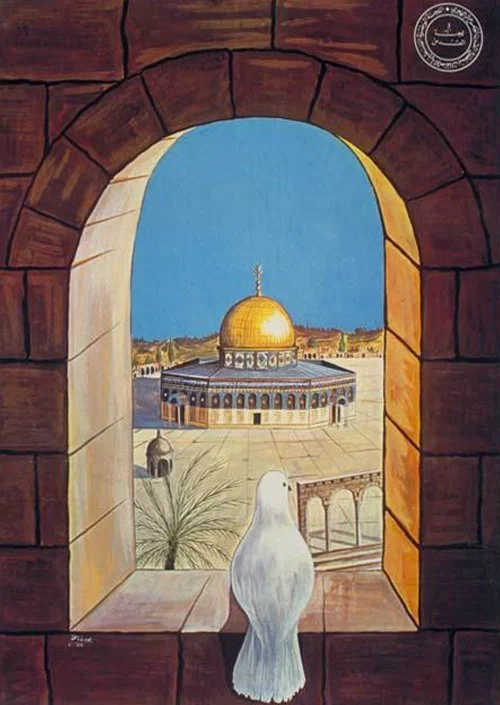

A Window on Jerusalem. by Yusuf Hammou. 1979.

Palestine is My Homeland. by Farouk R. Bayir. 1977.

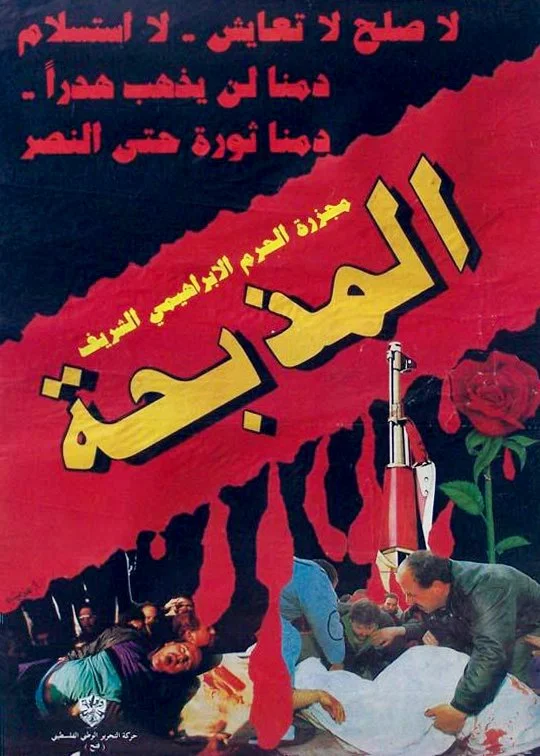

Sheikh Ibrahimi Mosque Massacre. by Amin Areesha. 1994.

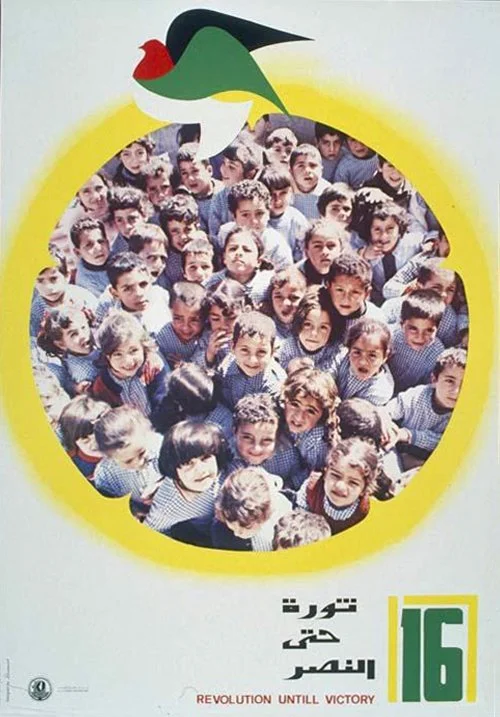

Revolution Until Victory. by Ismail Shammout. 1981.

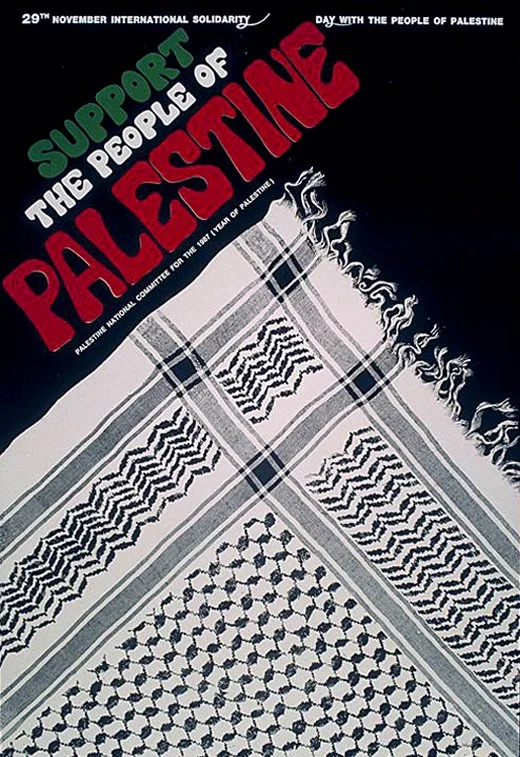

Support Palestine. Artist unknown. 1987,

Where Was the UN? by Ghazi Inaim. 1982.

Palestine National Youth. Artist unknown. 1985.

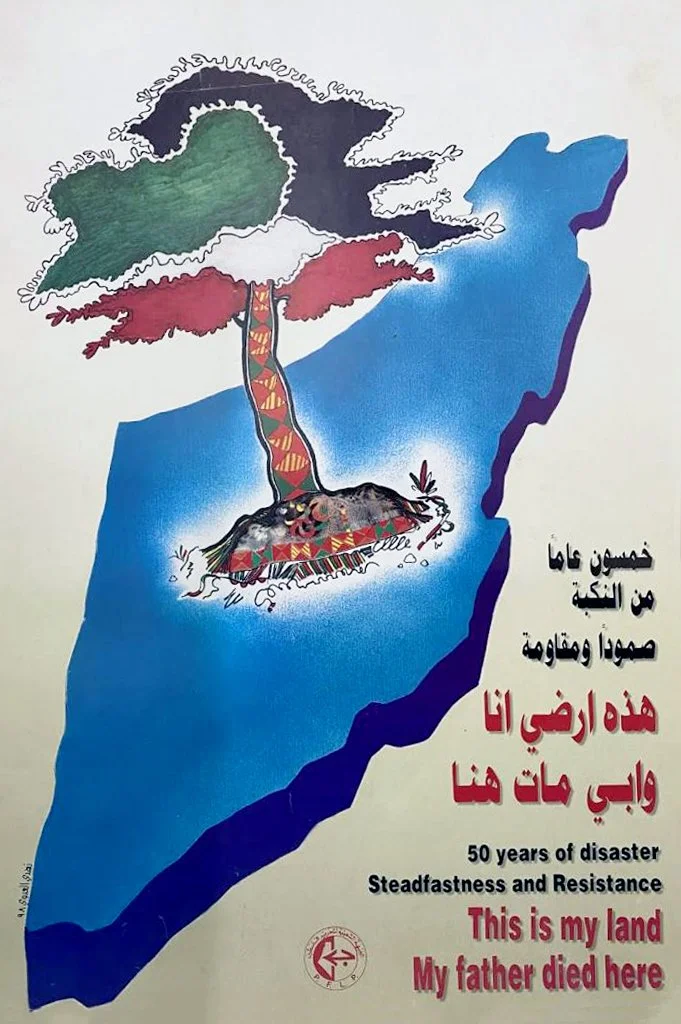

Disaster, Steadfastess, and Resistance. by Zuhdi El Adawi. 1998.

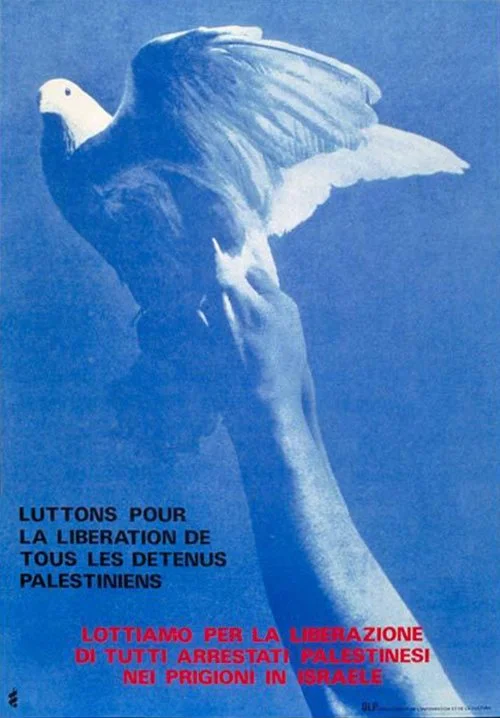

Lottiamo Per La Liberazione (Let’s Fight for Liberation). Artist unknown. 1990.

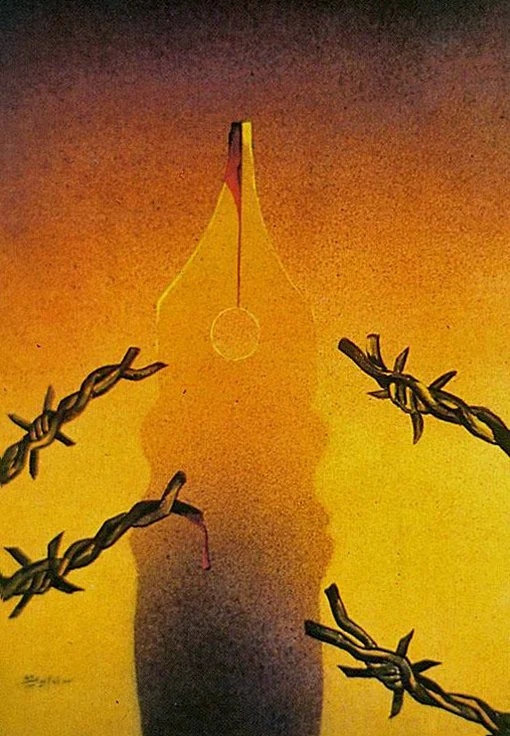

The Pen Is Mightier. by Adnan Al Zubaidy. 1990.

Last Updated

2024

Images via

Palestine Poster Project website

Palestine Poster Project Instagram

Info sources

TRT World

The Next Generation by Sascha Manya Crasnow