Insights into

Palestinian Art History

To learn about Palestinian art is to learn about Palestinian history.

The evolution of Palestinian art, particularly as a form of national identity, is inextricably tied to the shifts of the country itself. Moments such as the 1948 Nakba were key points in time both for Palestine overall and for how it impacted the arts specifically.

Resources

The information on this page includes research from the books:

Palestinian Art: From 1850 to the Present by Kamal Boullata, 2009

Liberation Art of Palestine: Palestinian Painting and Sculpture in the Second Half of the 20th Century by Samia Halaby, 2001

The Origins of Palestinian Art by Bashir Makhoul and Gordon Hon, 2013

And the PhD dissertation of:

The Next Generation: Shifting Notions of Time, Humor, and Criticality in Contemporary Palestinian Art by Sascha Manya Crasnow, 2018

Additionally, supplemental online research has been used to fill in certain gaps of this page. This includes sources such as The Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question, a joint project by the Institute for Palestine Studies and the Palestinian Museum.

Palestinian artists have largely taken it upon themselves to document their art history. Ismail Shammout published الفن التشكيلي في فلسطين (Art in Palestine) in 1989, the first book-length study of Palestinian art. There are select Arabic texts about Palestinian art history that have not been read yet for this page, as well as some other English texts not currently available.

Disclaimer

In Kamal Boullata’s book, Palestinian Art, he writes his own disclaimer:

“From art created at home during different periods of Palestine's history to art created in different places of exile, this book does not claim to be comprehensive in any way. It is only an attempt to reconstruct key pieces of 'the larger picture’ of Palestinian art... Its sole ambition has been to lay the foundations of an art history and set up a framework.”

Likewise, the art history coverage of this site follows that same intention.

Also mixed in to this page will be some general historical context, which again is not meant to be entirely comprehensive. This information is simply to help try to aid in understanding how, when, and why some larger moments happened that impacted the people and the art.

Details for this page may continue to be added to over time.

To view this history by divided pages instead, click here.

Traditions & Innovations

1800 - 1914

A starting point to look at the history of Palestinian art from information that is available and work that is documented. Including how art began to change within a religious framework at the turn of the 20th century, leading up to World War I.

The Painting of Icons

In the book The Origins of Palestinian Art, Bashir Makhoul and Gordon Hon say that they do not consider Palestine, nor Palestinian art, to have a fixed origin in time – an exact moment to point to as the moment of creation.

Instead, how far back we go is just dependent upon the information available from history, they essentially say. In Palestinian art literature, typically the 1800s are considered a good place to begin, they say, considering that we have an understanding of some of that era.

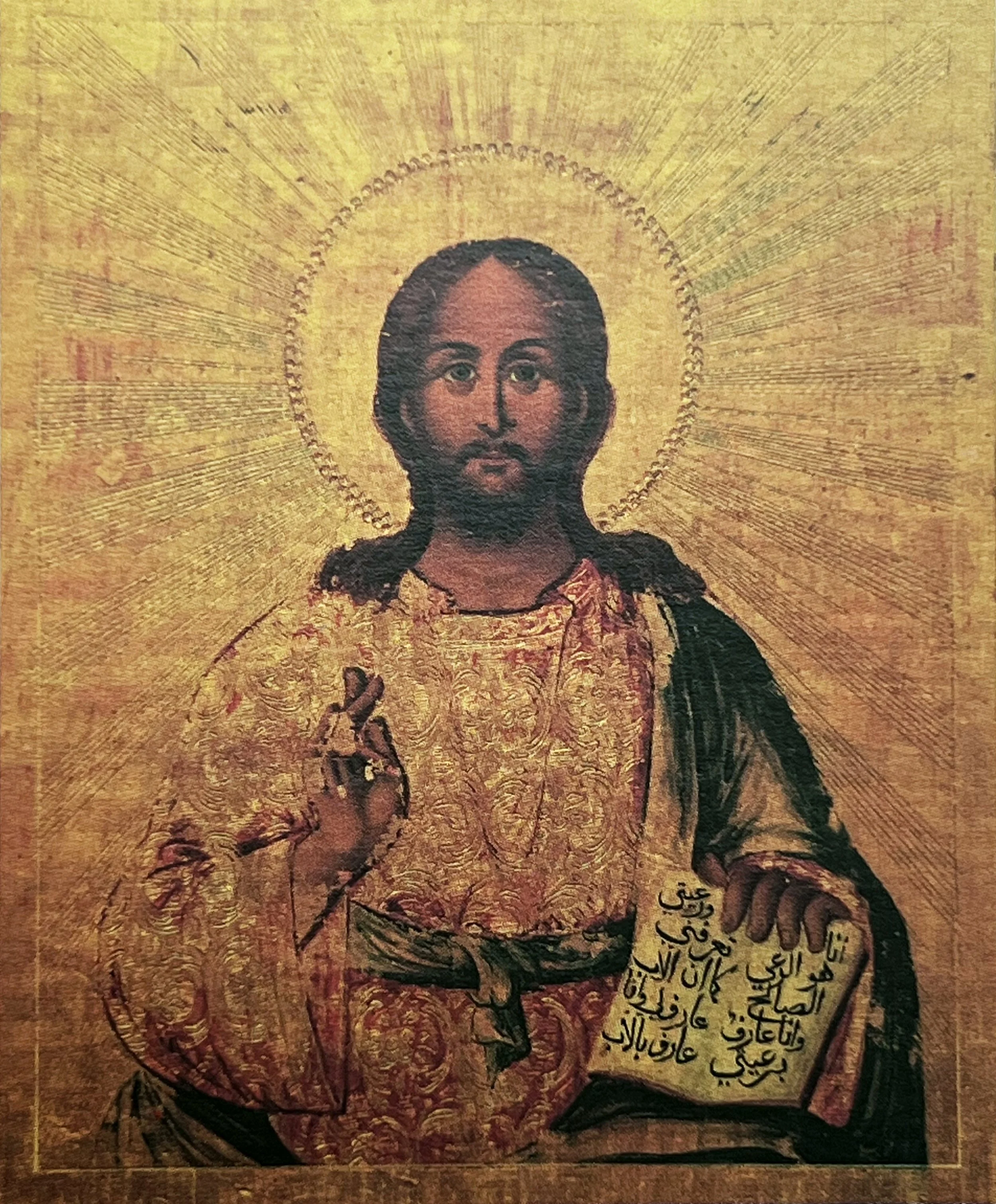

Christ Pantacrator from the Arab Orthodox Church

Artist unknown

via Palestinian Art book

At the time of the 19th century, artists were following a long tradition of pictorial painting icons and portraits, especially in Al Quds (Jerusalem). In Kamal Boullata’s book, Palestinian Art, he writes:

“The tradition of Byzantine icon painting, whose craft and precepts were formulated by the end of the fifth century, was the major pictorial living tradition handed down the ages throughout the Mediterranean world.

The seventeenth century, which marked the decline of this thousand-year-old painting tradition, heralded the beginning of a renaissance in Arab regional schools of religious painting whose iconographic language was borrowed from Byzantine models.”

Artists from the Jerusalem School followed the Byantizine tradition of icon painting, but The Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question writes they adapted it by using “characteristic features of the Arab folk hero in the popular arts and Islamic miniatures flourishing in Arab visual tradition.”

Icons made at the Jerusalem School were part of homes of the Arab Orthodox community in Palestine and the churches they frequented, as well as throughout The Levant. Additionally, Boullata notes, small icons were sought by those who traveled from the Ottoman Empire. The iconographers were also commissioned by convents and monasteries in Lebanon and Syria to do painting and restoration assignments.

“The painters took pride in signing their icons in Arabic with the first name usually appended by al-Qudsi, meaning the Jerusalemite,” writes Boullata, with Al Quds being the Arabic name used to describe the Old City. He also says that artists in some cases went by al-Urushalimi, “which is the biblical title identifying a Jerusalemite.”

This included Hanna al-Qudsi, who reportedly did this first, as well as others such as Mikha'il Muhanna al-Qudsi or Yuhanna Saliba al-Qudsi.

Paintings of Mikhail Muhanna al-Qudsi from 1882 – Saint George (left) and The Virgin Mary (right)

Artist unknown

via Palestinian Art book

In writing about this tradition, Boullata shares some wider historical context:

“The principal contributing factor to the Arabization of the Byzantine icon was the deteriorating relationship between the Arab adherents of the Orthodox Church and the clerical hierarchy successively headed by Greek patriarchs who kept total control of church affairs while the Church's Arab clergy and parishioners were neglected.

The Arabized icon was thus a form of expression of independence from Greek control of the Church that had been consolidated by the Ottoman authorities ever since they took over the region in the sixteenth century. The development in icon painting further coincided with the growing awareness of national identity in the provinces that had fallen under Ottoman rule.

In fact, when the first Arab Orthodox Patriarch was elected in Damascus in 1899, the event was considered by cultural critics from the region as a groundbreaking victory for Arab nationalism.”

This period and transition of how the art was created and identified – and what it represents – was, in Boullata’s eyes, “the indigenous beginnings of a personalized form of painting in Palestine.”

An Invention: Photography

While icon painting may have been around for centuries, there was a new visual art format that developed in the 19th century.

In 1839, the daguerreotype photography approach was invented and introduced to the public by French artist Louis Daguerre, which was the first publicly available photo process.

Later that same year, French painter Frédéric Goupil-Fesquet came to photograph the Old City. Many Europeans did the same during the rest of the century, who primarily were interested in photographing holy sites.

Before that point, people only had access to reading or seeing drawings and paintings of well-known places around the world. In this case, these photos held notable interest to many as a holy site.

Dome of the Rock at Al-Aqsa Mosque

Photo by French photographer Maxime Du Camp in 1850

During this time, photography was also picked up as a craft locally. Around 1860, the first photo studio was started by an amateur photographer named Yessai Garabedian, a priest who would soon become the Armenian Patriarch of Jerusalem.

The students of the school became the first local photographers in Palestine. The most notable early example was Garabed Krikorian, an Armenian-Palestinian who would go on to open his own studio. Krikorian also trained Khalil Raad, who was born in Lebanon originally. Raad is considered the first Arab photographer to gain recognition in Palestine. More continued to follow in their footsteps.

Photo by Khalil Raad, 1876-1918 collection

via Institute for Palestine Studies

Photo by Khalil Raad, 1876-1918 collection

via Institute for Palestine Studies

A Secular Shift

Nicola Saig – also written as Nikolas Saig – is viewed as the earliest well-known Palestinian artist, according to the later writing of artist Ismail Shammout.

Saig was one of several early Christian and Muslim painters in Palestine who started as iconographers, continuing the tradition of the 19th century.

However, these artists also started to create religious paintings that were no longer in the form of icons specifically, while still maintaining a sense of the history and tradition.

The Conversion of Saul

Painting by Nicola Saig, year unknown

Towards the end of the 1800s and early 1900s, this shift ultimately led to artists painting secular (non-religious) pieces as well.

Part of the inspiration for this shift was due to influence from Russian painters, who had been bringing their own dynamic to icon painting. They noticed how those painters living there at the time drew inspiration for their religious paintings from the local scenery and how the figures in their paintings drew on the local people, embracing Arab features. Catholic painters who had came from Rome to local convents also made an impact.

In The Origins of Palestinian Art, Bashir Makhoul and Gordon Hon write about how quickly this happened – noting it was “extraordinarily abrupt compared to the history of painting in Europe, where centuries of painting had elapsed since the Renaissance and where secular figurative painting was reaching its end just as it was beginning in Palestine.”

Saig – who had built his reputation on his large icons and art restoration skills – started to make oil paintings of peasants, landscape points of the local countryside, and scenes inspired by historical events.

(Untitled)

Painting by Tawfiq Jawhariyyeh

via Palestinian Art book

In Kamal Boullata’s book, Palestinian Art, writes:

“As elsewhere in the world, the transition from religious to secular painting in Palestine was a major step in the development of the language of art.

The change in emphasis did not come as a result of the artist's conversion from religious belief to a secular view nor did it come about simply as a result of being exposed to new tools and methods of painting. Rather, it came as a result of understanding the new knowledge disseminated by the changing world around him or her and by what the artist does with that knowledge.”

Al Quds / Jerusalem remained the center for this developing “national form of visual expression” as the local iconographers incorporating these new ideas were leading the way.

Saig’s studio there was also an important place for artists to hang out and develop. This included the Jawhariyyeh brothers – including Wasif Jawhariyyeh, who would go on to become a musician/poet, and Tawfiq Jawhariyyeh, who would become an photographer/painter.

WWI + British Mandate

1914 - 1922

A mix of historical and art context for a formative period of transition in Palestine.

Ottoman Empire Transition

Since 1516, the land of Palestine had been under control of the Ottoman Empire over the course of four centuries.

Ayşe Betül Aytekin describes this in an article for TRT World as “a period marked by peace, harmonious coexistence and flourishing of local culture.”

In particular, it was a time when three monotheistic religions coexisted without conflict.

“For the Ottomans, Palestine’s importance stemmed from its historical capital Jerusalem, which is regarded as Islam’s third holiest city after Mecca and Medina. For the Ottoman dynasty, which already held the Islamic Caliphate, the stewardship of these lands was viewed as a sacred duty.

And yet, given Jerusalem’s position as sacred to the two other Abrahamic religions, it never tried to disturb the harmony that existed between believers of different religions who lived in the Holy Lands.”

However, the Ottoman Empire had weakened by the end of the 19th century, including losing areas like Algeria, Tunisia, and Kuwait.

In 1914, World War I began. The Ottoman Empire fought as part of the “Central Powers” aligned with Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Bulgaria. They faced the “Allied Powers” of France, Russia, Italy, Romania, Canada, Japan, Great Britain, and later the US.

In 1917, the British invaded Palestine, where significant fighting took place in Gaza at first. The British then headed towards Al Quds and eventually won. In December, mayor Hussein Salim al-Husseini announced the surrender of the city.

Surrender of Jerusalem to the British Battalion, on December 9, 1917

Painting by Nicola Saig

via Institute for Palestine Studies

Husseini Surrender

Painting by Nicola Saig in 1918

via Palestinian Art book

One of the paintings that Nicola Saig did shortly after was based on a photograph taken of the moment of the city’s surrender. This work is described as a turning point in Saig’s career for showing that he was not only able to work within religious iconography but also compete with any modern way of reproducing images of reality, including of those in the local community.

This photo-to-painting rendition was not meant to just be a direct copy. Though Saig clearly had the ability to be fully accurate, he chose to make it his own as well.

“At first sight, the alterations introduced into Saig's painting appear to be negligible. They include the reduction in the number of people appearing in the original photograph and the elimination of all the shadows of people stretched in its foreground.

At closer examination, one sees that Saig's slight alterations recompose the group in such a manner as to dislodge the centrality of the British officer in the photograph and show that Jerusalem's mayor has become the central character in the painting.”

British Control & Mandate

The Ottoman Empire did indeed fall, stopping their fighting at the end of 1918, losing control of their territories that included regions of Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, parts of Saudi Arabia, and of course Palestine.

The Treaty of Versailles signed in 1919 formally ended World War I, where The League of Nations was created as an international organization in the guise of maintaining world peace. As Susan Pedersen writes in her book The Guardians: The League of Nations and the Crisis of Empire, this “in effect internationalized colonial rule” and “affirmed rather than repudiated imperialism.”

Hand-colored 1919 photograph in Palestine

via Library of Congress

The League of Nations created “mandates” for countries who were deemed as not yet ready to govern themselves, often with ulterior motives.

With the British Mandate of Palestine, made official by the The League of Nations in 1922, they designated themselves control over the land. As part of it, they adopted the 1917 Balfour Declaration that had publicly declared Britain's position of "the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people."

This was aligned with the goals of the Zionist movement, which had formally been established in 1897 with Theodor Herzl at the helm. As noted in Al Jazeera:

“In the 1880s, the community of Palestinian Jews, known as the Yishuv, amounted to three percent of the total population. They were apolitical and did not aspire to build a modern Jewish state.

But in the late 19th century, the Zionist movement - a political ideology - grew out of Eastern Europe, claiming that Jews were a nation or race that deserved a modern ‘Jewish state’. The movement, citing the biblical belief that God promised Palestine to the Jews, began to buy land there and build settlements to strengthen their claim to the land.”

In the forthcoming years, the British would encourage many Jewish settlers as they pursued a path that sought to implement the goals of Zionism and ignore the actual desires of the Palestinian community.

In The Origins of Palestinian Art, Bashir Makhoul and Gordon Hon write:

“The land on which (Palestinians) had lived and that they had cultivated for generations had become political real estate in a political economy from which they were excluded. Even legitimate ownership of the land carried little weight in that kind of economy. The urban Palestinian political elites that had grown under Ottoman rule and through which the Palestinians had gained some access to the international stage found themselves, under the British, reduced to restless natives.

What was really meant by 'a land without a people’ was a land without a state. The Zionist movement from the beginning understood what was meant by the modern Western construct ‘nation-state.’ They knew that ultimately it did not matter how many people lived there or how deeply entwined their cultural roots were with the history of the land. Without a state, the Palestinians had no sovereignty over their land and, within particular readings of the definitions of this construct, were not therefore a people.”

Art Across Time

In 1920, Nicola Saig did a painting that spoke to both the past and present moment. The goal was to share what Saig had experienced through his life prior to the British Mandate, an equilibrium between the local religious communities.

Caliph 'Umar at Jerusalem Gates

Painting by Nicola Saig, 1920

The painting featured Caliph ‘Umar, described as an early convert of Islam and one of the close companions of the Islamic Prophet Muhammad who reigned from 632 to 634 CE, during the Seige of Jerusalem in 637 CE.

Boullata writes that it brings to mind Byzantine icon depictions of Christ's Entry to Jerusalem, which typically show him in profile riding on a donkey as people go out to greet him at the city gates among palm leaves. “In his attempts to express his experience of Jerusalem’s interfaith harmony,” Boullata writes, “Saig endowed the image of the Muslim conqueror with the Christian traits of the Prince of Peace.”

The painting found great success and was looked at as an iconic representation of Islam's pacifist conquest of the city. The work would go on to be reproduced in schoolbooks.

Art During Mandate

1922 - 1947

After the British Mandate was imposed, life was not ideal. Art, however, did gain steam.

From Students to Teachers

A young artist during this time of transformation for Palestine was Daoud Zalatimo, who was born in 1906 – just before the start of World War I and the Ottoman-British transition.

Zalatimo’s family had a bakery around the corner from Nicola Saig’s studio. He often spent his free time there, finding himself enamored by Saig’s icons and paintings.

At the same time, Zalatimo was friends with the Jawhariyyeh family of brothers, who were also artists. The eldest, Tawfiq, helped nurture his artistic appetite and aptitude.

When the British reign brought in jobs for teachers in elementary schools, Zalatimo got a job at as an art teacher. He started in Khan Yunis and later went to Lydda school, which was closer to home. This provided him a reliable income and proved to elders in his community that art wasn’t a waste of time.

Zalatimo also took summer workshops offered by British art instructors who worked in the Mandate's Department of Education, so he was able to refine his skills. At this time, there were also more art supplies accessible.

The Painter’s Son by Daoud Zalatimo, exact year unknown

As a teacher, Zalatimo saw how his students were inspired by young nationalist poets like Ibrahim Tuqan and Abd al-Rahim Mahmud. Boullata writes that Zalatimo wanted to “demonstrate to his students how visual expression could be as emphatic as written language.”

“The choice of his subject matter, however, had to be carefully thought out if he were not only to avoid the possible wrath of more conventional Muslims among his larger audience, but more importantly to ensure their approval. Zalatimo had to walk a tightrope between his Arab viewers and his British employer. Were he to paint a subject matter esteemed by his compatriots who were vehemently opposed to British policies in Palestine, he could well invite a quarrel with his British employers.

It was in Saig's metaphoric interpretations of historical moments in Islamic history that Zalatimo found an ideal model to emulate. His work, initially displayed as an educational aid within the walls of the school in which he taught, thus expounded themes that were eventually to win the hearts of every Arab of his day, regardless of religious affiliation, and at the same time it did not displease the British who could not see it with the same eyes.”

Zalatimo would draw and paint portraits of historic Arab figures from Islamic history, as well as imagined versions of historic scenes. They successfully caught the attention of students. One of them was a young Ismail Shammout, who Zalatimo taught and mentored.

Other national school principals requested duplicates of Zalatimo’s paintings to display at their own schools, too.

Painting of Sharif Husayn by Zulfa al-Sa’di, 1940

1st Palestinian Art Exhibiton

Nicola Saig’s influence also extended to his first known woman student, who also was an apprentice: Zulfa al-Sa'di.

Sa'di continued to create and her work was exhibited in the Palestine Pavilion of the First National Arab Fair, hosted in 1933 at the Supreme Muslim Council outside Jaffa Gate. This was not just any show, it was the first documented art exhibition in Palestine.

It was a significant moment and impressed national figures who attended. Sa'di presented both oil paintings (portraits, still life, landscapes) and embroidery work – though her paintings received the most attention, which one guest noted made “the images speak.”

Kamal Boullata writes about the show in his book Palestinian Art,:

“Al-Sa’di’s exhibition represented an unprecedented cultural event in which image-making was for the first time officially recognized as a language that could enact an analogous role to that traditionally played by Arabic poetry, that is, in expressing collective aspirations through a personal voice. The Fair's jury granted al-Sa'di the first prize.”

In particular, her portraits deviated from the work of others at the time with close-ups that emphasized – especially when exhibited side-by-side – that “individual human beings and not faceless masses shape history and culture” as Boullata describes. She painted cultural, political, military, and educational figures who had special meaning to both Palestinians and the larger Arab community.

1st Female Professional Photographer

As photography developed, it wasn’t until a couple of decades into the 20th century that the gender of who was behind the lens started to change. Karimeh Abbud is referred to as the first Arab and Palestinian woman to be a professional photographer.

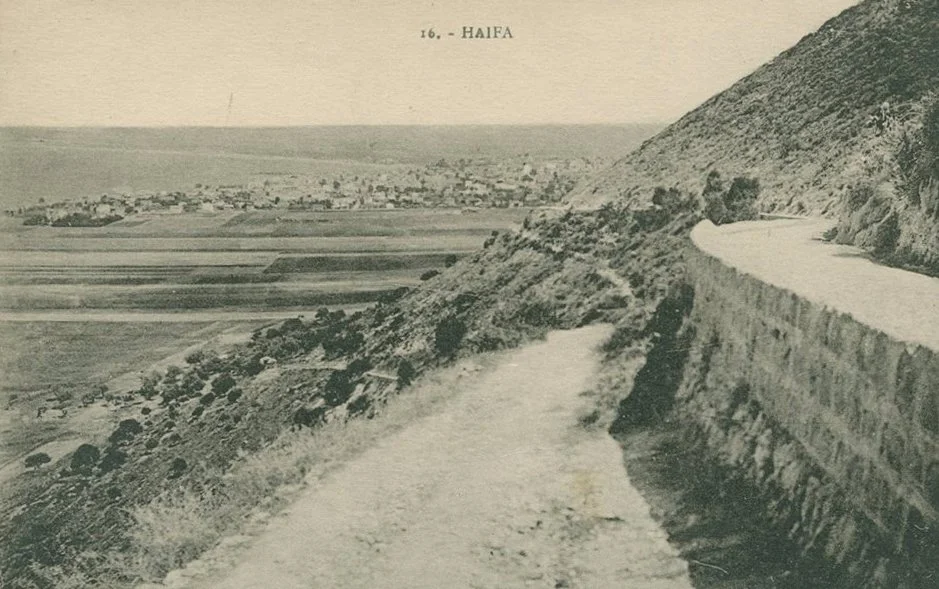

After getting a camera from her father in 1913, Abbud also often accompanied him on work trips to other cities and villages, which provided an opportunity for her to take photographs across the country – including Bethlehem, Tiberias, Nazareth, Haifa, and Qisarya.

Photo of Haifa by Karimed Abbud

Colorized version of the same photo, as Karimed Abbud was known to add color to her prints

Taking photos of other parts of Palestine would remain a part of Abbud’s work, but it was her photos of people that helped turn it into a feasible career.

Karimeh Abbud behind the lens of her camera

The Institute for Palestine Studies writes that Abbud began to earn money taking portraits of woman and children, and then by wedding and ceremonial pictures. She started in the early 1920s with a studio in her home and later rented out a dedicated photo studio by the early 1930s.

Women felt more comfortable with her behind the lens, including those from conservative families. They even traveled from all over the country to get their portraits taken.

Abbud would go on to establish spaces in other cities, too, with studios in Nazareth, Bethlehem, Haifa, and Jaffa.

She would develop the pictures in her own darkroom, importing printing paper from Egypt. Adding color to her prints also brought her recognition.

Her work was not discovered until around the turn of the 21st century, but we can now recognize and understand the importance of Abbud’s place in photography history.

A mixture of photos by Karimeh Abbud

A Start in Filmmaking

Dubbed as the first Palestinian filmmaker, Ibrahim Hassan Sirhan’s first noted work is a 20-minute silent film documenting the King of Saudi Arabia’s visit to Palestine in 1935. He filmed this with cinematographer Jamal al-Asphar. A couple of years later they worked together again – this time on a 45-minute film, Realized Dreams (1937), about Palestinian orphans.

Sirhan also started the ‘Studio Palestine’ production studio in 1945 with another Palestinian filmmaker Ahmad al-Kilani, who had just graduated from a school in Cairo. Their studio made several feature-length films that were screened nationally and in nearby Arab countries.

Al Hambra Cinema in Jaffa, Palestine (1937)

via Library of Congress

As far as movie theaters, the first (The Oracle) had been developed in Al Quds at the start of the 20th century.

But it was in 1937 that the largest theater in Palestine – and all of the Middle East – opened in Jaffa: Al Hambra Cinema.

Al Hambra not only played movies but also hosted other well-known Arab artists for events. This included concerts for musicians such as Umm Kulthum and Farid al-Atrash.

By 1948, there were reportedly 40 cinemas across the country. During this time, films had to be approved to watch by the British, with mostly Egyptian and American films being played at the time.

Historical Context: The Arab Revolt

After the Ottoman Empire had ruled for centuries in finding co-existence between civilians of multiple religious faiths, that shifted after World War I and the implementation of the British Mandate.

Art may have grown during the time of the official Mandate period from 1922 to 1948, but there was also a rising of tension between Arabs and Jews.

Britain ushered in large numbers of European-Jewish settlers during the 1920s from the start of their rule. The Balfour Declaration had made it clear that Britain’s commitment was to Zionism and the establishment of a Jewish state in a land that had a majority Arab population.

The Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question writes about the continued influx of immigrants, and the impact, around the time of The Great Depression:

“In Palestine, as elsewhere, the 1930s had been a time of intense economic disruption. Rural Palestinians were hit hard by debt and dispossession, and such pressures were only exacerbated by British policies and Zionist imperatives of land purchases and ‘Hebrew labor.’

Rural to urban migration swelled Haifa and Jaffa with poor Palestinians in search of work, and new attendant forms of political organizing emerged that emphasized youth, religion, class, and ideology over older elite-based structures.

Meanwhile, rising anti-Semitism — especially its state-supported variant — in Europe led to an increase of Jewish immigration, legal and illegal, in Palestine.”

This only continued to grow. “In the 1930s, after the Nazis had come to power in Germany, Jewish immigration intensified, reaching its peak in 1935 when 61,000 Jewish immigrants entered Palestine,” notes Al Jazeera.

In addition to wanting to justifiably manage the large swaths of immigration – increasingly through illegal means – and land purchases as part of a Zionist mission, Palestinians wanted an end to the British Mandate. They wanted independence.

The Institute for Palestine Studies writes about the British military’s use of power during this time, leading to a growing dissatisfaction:

“The colonial state intruded upon all manner of daily activities, degrading Palestinians' living conditions and turning the mundane into a site of contest and a pressure point through which to exercise power. The colonial regime converted schools and hotels into military bases, seized crops and livestock, and invaded, assaulted, and demolished homes, villages, and urban quarters.

Quotidian and ritual activities like attending prayers or going to school were made contingent on docile behavior or random circumstance; even funerals were prohibited as potential ‘disturbances.’ Villages were temporarily incarcerated and the movement of goods and persons was restricted and rendered dependent on compliance with state surveillance.

The rebels were determined to build an alternative sovereignty and public realm that would incorporate the Palestinian population.”

British soldiers frisk a Palestinian man in Jerusalem, late 1930s

Photo by Khalil Raad

via Institute for Palestine Studies

One person who played an important role during this time was Izzeddin al-Qassam.

Qassam had his first experience leading his own group of rebel fighters in his home country of Syria in 1919, facing off against French forces in the territory that had also been under Ottoman control. After they were ultimately defeated, he fled to Haifa in Palestine where he was a teacher, imam, preacher, religious official, and more. But he eventually sought to further organize and fight back against foreign control. As noted in the Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question:

“Qassam followed closely the growing menace of Zionism as a result of British support of the ‘Jewish National Home,’ and he became convinced that Britain was the root cause of the problem and that only armed struggle could restrain the Zionist project.”

In November 1935, he and a group of a dozen soldiers fought against a large British army in the forests of Ya‘bad (in the West Bank), a battle in which Qassam did not make it through alive. The next morning, Haifa declared a general strike and there was the biggest funeral the city had ever seen. There was a sizable public outrage.

Qassam played a key part in inspiring a larger rebellion. In 1936, Palestinians called for a general strike, a withholding of taxes, and the closing of municipal governments. Soon, this escalated into larger fighting that saw British forces (along with armed groups of Jewish settlers) clash with Palestinian fighter groups over the upcoming years.

The Martyr Izzeddin-al Qassam

Later artwork by Burhan Karkoutly in 1980

via Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question

Lasting for three years, this period of rebellion from 1936 to 1939 is referred to as the Arab Revolt, the Great Revolt, or similar titles. During this time, around 15% of the Palestinian male adult population was martyred, injured, imprisoned, or exiled.

During this time, the British set a precedent that would be followed by other armed forces in Palestine for years to come. Local fighters who were much more familiar with the land knew how to stay largely undetected. With British soldiers proving inadequate at finding those attacking them, they would instead indiscriminately take retaliation against all Palestinian civilians, businesses, goods, and more in villages of rebel strength.

“Having crushed the revolt, the British rendered Palestinians disarmed, leaderless, defenseless, and their demands for liberation unrealized,” writes Emad Moussa in The New Arab. “The Zionists, meanwhile, were aided to evolve into a semi-state entity with a significant military power that, in 1948, far exceeded in equipment and troops whatever was left of Palestinian resistance and Arab armies combined. The ethnic cleansing of Palestinians was inevitable.”

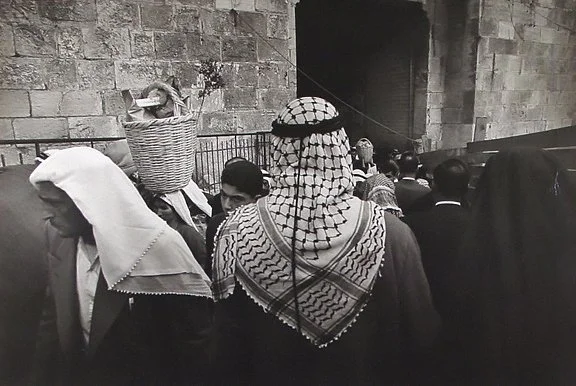

Older photo of a person wearing a keffiyeh

Photographer and exact year unknown

Keffiyeh As A National Symbol

The revolt was also the birth of the keffiyeh scarf being used, starting a long tradition that has kept going ever since.

It’s also spelled in English as kufiyyeh, kufiya, and other variations.

As Samaa Khullar wrote in Everything You’ve Heard About the Keffiyeh Is Wrong for The Nation:

“There is no clear definition amongst historians about what the design of the keffiyeh means, but some Palestinians say each pattern has come to represent a different part of Palestinian life.

The bold black lines on the edge of the scarf are said to symbolize historic trade routes; the fishnet pattern reflects Palestinian ties to the Mediterranean Sea; and the curved lines represent olive trees, one of the agricultural staples of historic Palestine.

The rise of the keffiyeh as a symbol of solidarity, however, mirrors issues of state surveillance that we still see today.

During British colonial rule in Palestine in the 1930s, rural freedom fighters — known as fedayeen — began resisting occupation and were easily identifiable by their head scarves.

As a result, Palestinian men in urban areas, who had previously donned the Ottoman-style fez, answered calls to stand in solidarity with the fedayeen and remove class identifiers by wearing the keffiyeh.

The keffiyeh scarf, still used to this day

Photo by Armando Franca/AP

In 1936, during the Arab Revolt, Palestinian nationalists also began to use the keffiyeh to conceal their identity and avoid arrest by British colonial forces. Much like today’s lawmakers in the United States, the British unsuccessfully attempted to ban the headscarf, because they could no longer identify who was an urban Palestinian and who was a revolutionary. (Their solution to this challenge was to indiscriminately kill everyone.)

As Jane Tynan, an assistant professor in design history and theory at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, told Middle East Eye: ‘From its function in the revolt as a tool to disguise the identity of the wearer from British authorities, the keffiyeh became shorthand for the Palestinian struggle’.”

Community Starting To Form

Kamal Boullata writes that the end of the British Mandate period saw a growing art system.

This was particularly true in Al Quds / Jerusalem, which he notes was the country’s cultural and political center. The recently-established Islamic Museum (est. 1923, at Al-Aqsa) and the Palestine Archaeological Museum (est. 1938) frequently hosted exhibits, performances, and lectures.

In addition, Palestinian collectors and art connoisseurs began to increase – including by Ragheb Nashashibi, Tawfiq Kan’an, Wasif Jawhariyyeh, and Ya'coub al-Husseini. The artists themselves also continued to build community, notes Boullata.

“While the older generations of iconographers and craftspeople continued to meet at Nicola Saig's studio in the Old City, the studios of Jamal Badran and Tawfiq Jawhariyyeh outside Jaffa Gate were gradually becoming a crossroads for a new breed of Palestinian craftsmen, aspiring painters, engravers and calligraphers who finished their studies abroad. They would meet there with collectors and with young and old art connoisseurs.”

He also describes this time as a “contagious period in which the visual arts were beginning to share the prominence that was traditionally reserved for the spoken or written word.”

Zoom Out:

1800 - 1947

This section pauses the chronology to take a step back and briefly look at the overall evolution of a couple of art forms during this larger period.

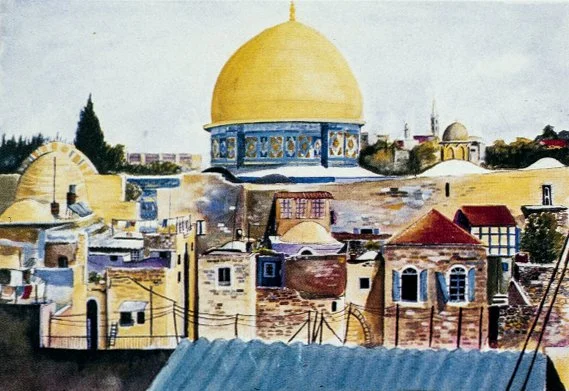

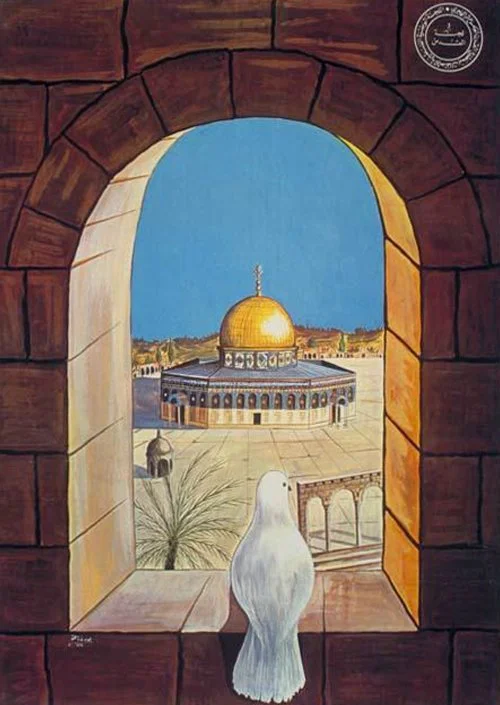

An untitled piece of the Dome of the Rock at Al-Aqsa Mosque

Artwork by Khalil Halabi

Initial Palestinian Artists of Record

The works made during this early time of art production often do not get as much attention or recognition, primarily due to lack of images available and sparse information.

Research for this section was particularly guided by Kamal Boullata’s book Palestinian Art: From 1850 to the Present, which is seen as a crucial resource to stitch together the threads of history during this time.

In The Origins of Palestinian Art, Bashir Makhoul and Gordon Hon go as far as to say that “Boullata's meticulous restoration of this period in the history of what was to become regarded as Palestinian art constitutes one of the most important detailed historical works on nineteenth-century Palestinian culture available in English.”

Several images in the previous sections were also used from Boullata’s book, as there are very limited images online when you search for the work of artists from this era.

The Mosque's Courtyard

Painting by Daoud Zalatimo, year unknown

via Palestinian Art book

In tracing the journey from the icon paintings to secular work, one can see the evolution of paintings as Palestinian artists entered the 1900s.

In order to adapt with the times as photography became a popular form of image-making, paintings also began to touch on more modern subjects of people and events. This would soon serve to be relevant to the art that followed.

A notable pattern that can also be seen is how artists passed down lessons, tracing a through-line between generations. After Nicola Saig set the precedent in teaching so many artists like Zulfa al-Sa'di or Daoud Zalatimo, that wisdom would continue to be passed down (with new additions and tweaks) to younger artists.

The Profession & Hobby of Photography

Photography as a line of work gained popularity throughout the country during the first half of the twentieth century. There was a need for a variety of photographers who specialized in different fields. From pictures of the holy land for tourists to studio portraits of married couples, soldiers, families, and more – there was plenty of variety to make one’s focus.

“By the time British rule in Palestine drew to a close in 1948, the profession of photography had spread extensively across the country,” says The Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question.

Photo by Khalil Raad

Bethlehem in 1920

via Institute for Palestine Studies

There were several active photographers, like the aforementioned Karimeh Abbud, but one worth looking at as a broader reflection of the period is the aforementioned Khalil Raad.

As the first known Arab photographer in Palestine, Raad had opened his photo studio in 1890 at Jaffa Gate. He continued to make work during the first half of the 20th century.

While many photographers tended to focus on studio portraiture, Raad documented everyday life, political events, archaeological sites, and more.

Photo by Khalil Raad

The Orthodox Christian procession on Easter from the Greek Patriarchate to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in the Old City of Jerusalem, 1910

via Institute for Palestine Studies

The Institute for Palestine Studies, of whom Raad’s archive was later donated to, wrote about his work:

“The photography of Khalil Raad combines an aesthetic value with a historical importance. In his work, there is nothing ‘folkloric’ as was sometimes the fashion in the work of some photographers who were successful in Europe.

On the contrary, his was a vision that showed a considerable sensitivity in its portrayal of daily life. One sees farmers and villages, town scenes all mixed in with portraits of Palestinian fighters, involved since the turn of the century, in the struggle against Zionist colonialism and the British Mandate.”

They explain how European photography at the time – such as with the French – took images where they suggested towns were empty and villages deserted. Raad’s work, instead dispelled “the myth perpetrated by colonialists in Palestine that it was an empty land peopled only by a few savages.”

Photo by Khalil Raad

A girl in traditional clothing standing in a field of wildflowers in springtime in Palestine

As part of Raad’s 1918-35 Collection

via Institute for Palestine Studies

Nakba: A Defining Time

1947 - 1950

Mostly historical information to provide context around a time that changed everything for Palestinian life altogether: the 1947 UN Partition plan and 1948 Nakba.

World War II

During the second world war, less than three decades after the first, Germany carried out a holocaust of six million Jewish people. It was, unquestionably, a tragedy.

Jews who fled persecution from the late 1930's through the early-to-mid 1940's were admitted – in limited numbers – to countries such as Spain, Switzerland, Portgual, and the United States. Many also attempted to go to Palestine.

After WWII officially ended in 1945, there was also the question of where all of the displaced Jewish people would go. At this time, the U.S. tried to persuade Britain to allow 100,000 of the ~250,000 total displaced Jews to go to Palestine, which was rejected.

Over this period, Britain went through a series of attempts to figure out next steps as they tried to temper the waves of illegal immigration and the Arab response to it.

Ultimately, they weren’t able to find an agreed-upon solution. As a result, they decided to pass the responsibility on to the United Nations.

UN Partition Plan

The United Nations had been created in 1945, succeeding the League of Nations, under the declared goal of protecting international peace and security.

In 1947, the UN General Assembly passed Resolution 181. This got rid of the British Mandate on Palestine, replacing it with a plan for partitioning the land into two states – an Arab and a Jewish state. (This also included declaring Jerusalem and Bethlehem as part of an international zone and to be administered by the UN.)

At this time, Jews owned about 6% of the land and were barely a third of the population. However, the UN partition allocated them 56% of land.

There was immediate pushback that the amount allocated for the Jewish state was unjust. Hundreds of thousands of Palestinian Arabs (both Muslims and Christians) would be forced to live in this Jewish State. It would also leave the designated “Arab State” without important agricultural lands and seaports.

The decision was rejected by the Arab community, who still wanted an independent, singular, and self-governing state – including full rights for both the country’s Arab majority and for the Jewish people who had already been there as legal citizens.

The plan continued in spite of the opposition. As the Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question notes, “it gave international legitimacy to the Zionist conquest of Palestine by force of arms.”

Beginning of the tragedy

Painting of the Nakba later on by Ismail Shammout, 1953

via artist archive

Nakba

Immediately after the UN plan in November 1947, Zionist forces began to target Arab villages and residential quarters.

This included forcibly displacing Palestinians from their homes both within the new “Jewish State” lines and outside of the UN border lines.

Zionist had several militias ready to fight and had already been importing a massive amount of arms throughout the British Mandate period. Palestinians, on the other hand, had no major official fighting groups at this time.

In the Spring of 1948, attacks ramped up dramatically after the official adoption of Plan Dalet, which was essentially a call for ethnic cleansing of indigenous Palestinian Arabs through the destruction of villages.

One of the most notable attacks was the Deir Yassin massacre at the start of April 1948 that left over 100 Palestinian martyrs. This was also used as a Zionist propaganda tool to spread fear. They wanted to get as much land as possible before the British Mandate reign officially ended, so they continued to attack villages.

Massacare of Dair Yaseen

Painting later on by Ismail Shammout in 1955

via artist archive

On May 14, 1948, the British forces withdrew. Afterwards, the “Declaration of the Establishment of the State of Israel” was announced by David Ben-Gurion, the first Israeli Prime Minister and former head of the World Zionist Organization. The United States also recognized the “State of Israel” on the very same day.

Neighboring Arab countries, who were harboring many refugees, went to war with Zionist forces after the self-proclaimed state declaration. Fighting continued into 1949, ultimately to no avail. By the end, more than 500 villages and 10 cities were depopulated. There were invasions, bombings of homes, looting, and destruction all around these areas.

This period of ethnic cleansing is referred to as Al-Nakba, which loosely translates as “The Catastrophe” from Arabic to English – though that does not do sufficient justice to what happened. (It is often referred to in English-language context just as the Nakba.)

15,000 were martyred and over 750,000 Palestinians (around two-thirds of the Arab population) were ethnically cleansed from their homes to either refugee camps within Palestine or to other neighboring countries like Lebanon, Jordan, and Syria.

Expulsion from the Homeland

Painting of the Nakba later on by Abed Abdi in 1967

via artist archive

Zionists had taken up 78% of historical Palestine. Overall, there was over four million acres of Palestinian land estimated to be stolen at this time.

There were around 150,000 Palestinians who remained inside the “Israeli” borders after, a quarter of whom were internally displaced. These Palestinians were technically given “Israeli citizenship” but lost most of their land and were subjected to a violent rule after.

From the territories remaining outside of these “Israeli” borders, those did not even become an independent Palestinian state either. Egypt took control of the Gaza Strip and Jordan took control of the West Bank and East Jerusalem, both places then becoming home to many refugee camps.

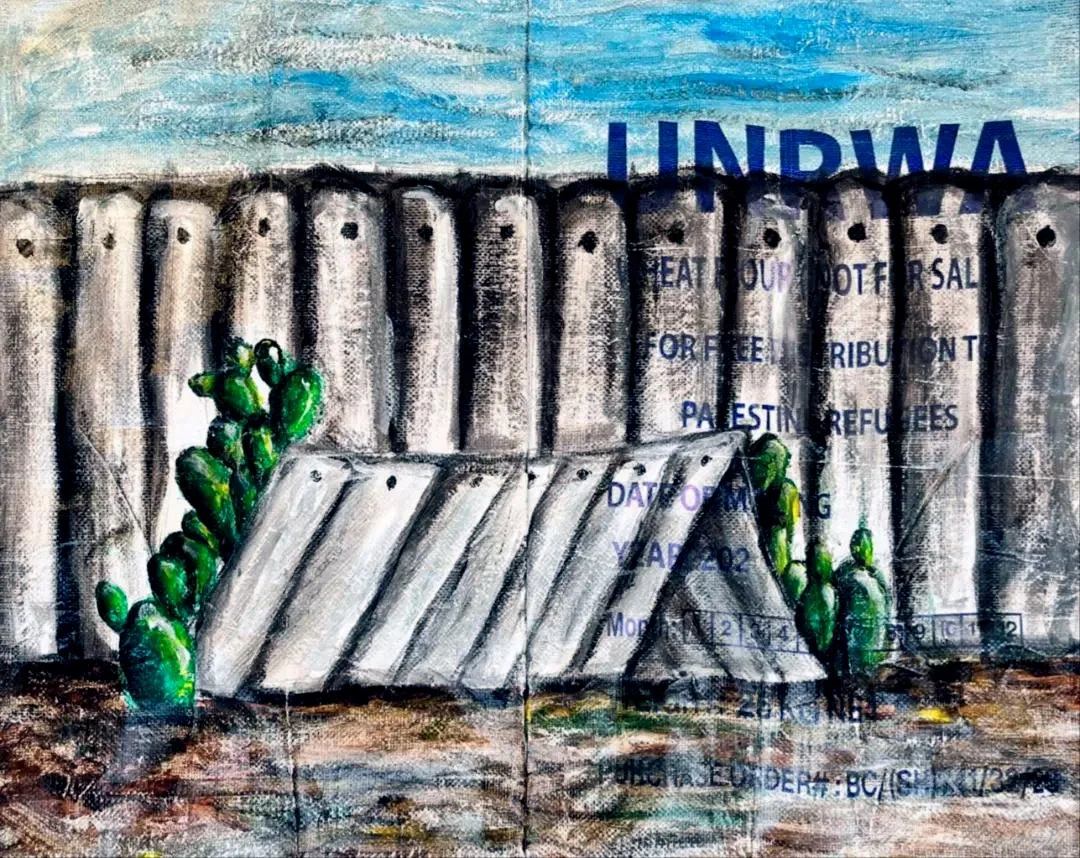

In December 1949, the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA) was established. In what was supposed to initially be a temporary program, the UN sought to provide temporary humanitarian assistance, education, work programs, refugee camp infrastructure, and more. However, this was a drop in the bucket after the damage of the UN Partition decision that led to the nightmare in the first place.

In addition to the immense human tragedy, Kamal Boullata writes about the impact of the previously-growing art scene after the Naka:

“Much of the art objects produced over the four decades preceding those bloody months were rendered irretrievable in the wake of the victors' widespread looting.

All traces of the cultural enterprise of Palestinian modernity were obscured, as its advocates were dispersed and the accomplishments of a century and a half of development in a native pictorial art were doomed to oblivion.”

Following The Catastrophe

1950 - 1967

How art took a new form in rebuilding after the Nakba, led by artists such as Ismail Shammout and Tamam Al-Akhal, and started to become integrated into organizations like the PLO and groups of freedom fighters.

After The 1948 Nakba

With nearly a million people displaced from the Nakba and many Palestinians now navigating a new life in refugee camps, life was forever changed.

Art – along with work, education, and culture – naturally came to an initial stop in the wake of this devastation.

In her book Liberation Art of Palestine: Palestinian Painting and Sculpture in the Second Half of the 20th Century, Samia Halaby describes the nation-defining event as one that “shaped the consciousness of the new generation of (Palestinian) artists.”

“They emerged from the tragedy ready to rebuild, but what they would rebuild was not known through their own experiences. To many, memory seemed to begin anew. Artists thought that everything they did was being done for the first time. To them the first show after 1948 seemed the first show ever, and the art of painting and sculpture after 1948 was wholly new to Palestinian history.”

Halaby also notes that Palestinians felt it was important to preserve the stories of the Nakba and their cultural history.

The First Steps After

Around five years later, a new era and generation of visual art for Palestine started. A defining point was a 1953 exhibition in the Gaza Strip that featured the work of a 23-year-old painter, Ismail Shammout.

At 14-years-old, Shammout’s family had been expelled from their village during the “Lydda Death March” of the Nakba, where Palestinians were not allowed to carry water. His two-year-old brother did not make it from the dehydration. After being at a Khan Yunis refugee camp in Palestine, Shammout found a way to go study in Egypt. He was still a student in Cairo at the time of this show.

This 1953 exhibition included a painting by Shammout of an old man walking with children – entitled Where To? – that would immediately gain attention. It was inspired by his own experience being displaced with his parents and siblings.

Where To?

Painting by Ismail Shammout, 1953

via artist archive

It was one of several paintings that brought the pain from the Nakba into visual depictions and immortalization. Refugees saw themselves in the work and the art was well-received. Shammout had another exhibition in Cairo the following year and a new chapter had begun.

Kamal Boullata sees this approach as a contrast to the Palestinian painters under British Mandate, like Nicola Saig, who used historical moments to metaphorically comment on current conditions. After the ‘48 Nakba, memory was instead used to express the experience of exile.

Ismail Shammout (right) at a follow-up exhibition in Cairo in 1954

via Palestinian Art book

Samia Halaby writes that the 1953 exhibition “marked the beginning of the liberation movement in its artistic form and was followed by a flood of individual and group shows by a new generation of artists.”

During this time, artists were also still able to travel across the West Bank, Gaza, and neighboring countries – like Amman in Jordan – all of which were under Arab sovereignty for the time being.

Al Quds remained a prominent area for the arts, and was where many artists came to in the late 1940s for those still in Palestine.

There were also patrons, such as Amineh El Husseini, who helped to support and promote young artists. Some of them formed clubs and groups who would exhibit together.

However, many Palestinians were also taking refuge in other countries – especially those displaced from villages in the ‘48 territories that had been taken over by Israeli Occupation Forces. In other countries nearby, like Lebanon and Jordan, refugee camps and communities formed there as well. These would also become locations of art scenes developing.

Art was seen by some as a way to implicate international viewers to at least force them to witness the tragedies of the Israeli crimes against the Palestinian people.

Beirut As Refuge

Kamal Boullata writes in his book, Palestinian Art, that this initial time of art development after the Nakba aligned with Beirut’s heyday as the “metropolis of Arab modernity.”

“1952 marked the outbreak of the Egyptian revolution, one of the first major direct consequences of Palestine’s fall and an important factor, through its nationalist and anti-imperialist policies, in the subsequent coups d'état in neighboring Syria and Iraq as well as in the political unrest in Jordan and Lebanon.”

In that same year, Lebanese art collector Nicolas Sursock left his large residence and collection to the city, in order to establish Lebanon’s first museum of contemporary art. The space in Beirut would go on to open its doors officially in 1961. During this time of the 1950s and 60s, galleries sprang up around Beirut to showcase work from artists around the city, art from the Arab world, and some from Europe and the U.S.

Beirut by Ismail Shammout, 1957

Palestinians in exile in Beirut included the aforementioned Ismail Shammout, who ended up going to there in 1956 to work at the UN Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA), where they established an office for commercial art and book design.

There was another Palestinian artist, Tamam Al-Akhal, who Shammout had exhibited with in 1954. She received a Teaching Certificate in Fine Arts in 1957 after studying on scholarship in Cairo. Al-Akhal then ended up in Beirut, where she began teaching art at a female-only college.

Refugee camp in Beirut by Tamam Al-Akhal, 1960s

In 1959, Shammout and Al-Akhal got married while both in Beirut. Together, they would continue to play an important and evolving role in Palestinian art for years to come.

Self-portrait

Painting by Ismail Shammout, 1957

via artist archive

Tamam (Al-Akhal)

Painting by Ismail Shammout, 1965

via artist archive

PLO Start & Embrace of Art

After years of deliberation on next steps among Arab nations, a meeting of a Palestinian National Congress in 1964 resulted in the establishment of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO).

This included a National Charter for the PLO, which emphasized the connection between the national-Palestinian and the pan-Arab dimensions of the struggle for Palestine's liberation. As The Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question writes about the charter:

“It declared the Balfour Declaration, the Mandate, the partition of Palestine, and the creation of Israel null and void, and saw in Zionism ‘a movement that is colonial in its emergence, aggressive and expansionist in its aims, fanatically racist in its nature.’

It called for the restoration of Palestine to ‘a condition of legitimacy’ and to enable its people to exercise national sovereignty and national freedom.”

Immediately after, the PLO opened an exhibition of artists in Al Quds to celebrate. “The show had such an impact that people began to think of art as part of the liberation movement,” writes Samia Halaby in her book, Liberation Art.

A year later, in 1965, the Arts & Culture department was founded with Ismail Shammout and Tamam Al-Akhal leading its efforts.

The first PLO logo created by Ismail Shammout, 1965

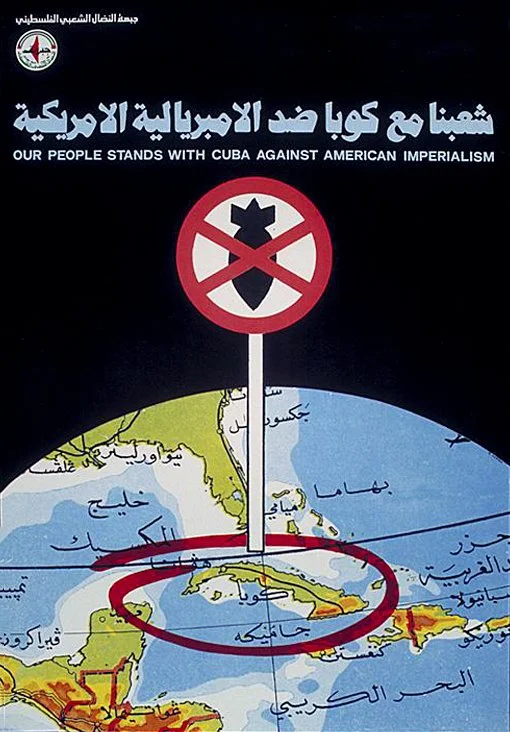

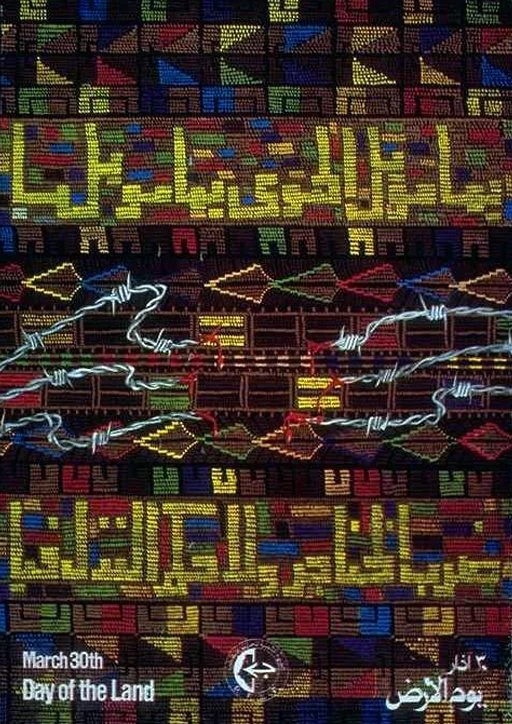

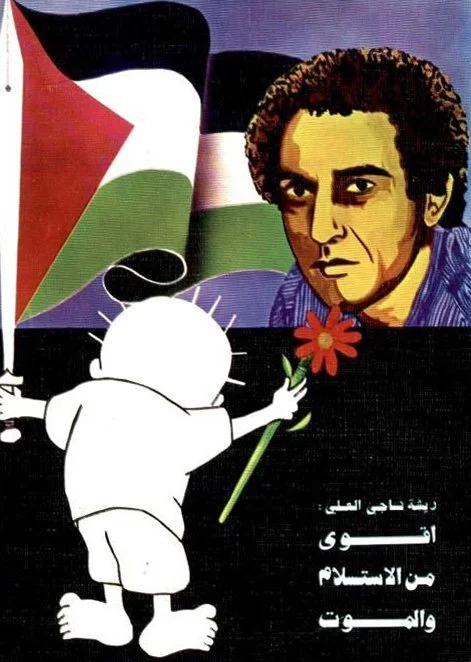

This included creating posters, which were becoming an increasingly popular art, marketing, and propaganda form. The Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question writes:

“Shammout designed the first set of posters ever issued, a total of four, with the caption ‘We All Are the Sons of Palestine.’ The posters communicated the simple message that the PLO was the representative of the Palestinian people and that it was a political body emerging from the masses. The same designs were reprinted in 1967 with the caption, ‘We All Are with the Resistance.’

While some artists donated labor, others were remunerated and some were employed in the organization and management of events. They produced and promoted films, photographs, reportages, pamphlets, and posters; the latter were the most effective, lightweight and low-cost means of visual and iconographic communication.”

The PLO Art Department also helped organize exhibits for Palestinian refugee camps, who would otherwise never make it into the art market or commercial galleries.

And since few Palestinian artists in Beirut were able to make a living from their art alone, most took on jobs that included teaching at UNRWA schools, working on construction sites, or freelancing in commercial art.

These Palestinian refugee camp artists included Ibrahim Ghannam, Yusif Arman, George Fakhoury, Imad Abd ar-Wahab, Jamal Gharibeh, Tawfiq Abdel Al, Muhammad al-Shair, Abd al-Hai Musalim, Husni Radwan, Michel Najjar, and more.

Don't Forget Palestine

Poster by Ibrahim Ghannam, 1955

One of the earliest designs in the Palestine Poster Project archive

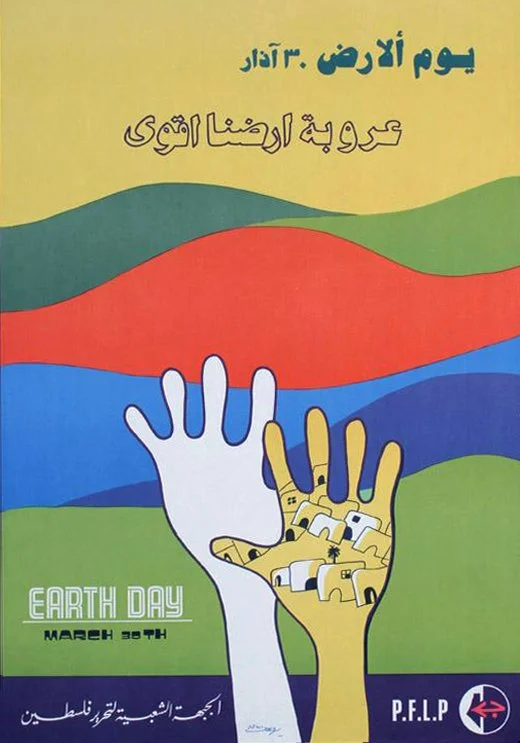

An Era of Poster Art Kicks Off

While there were some posters in the 1950s for Palestine, the medium became powerful in 1965 after the PLO launched their poster designs and other groups started to follow suit.

Like with Ismail Shammout, groups brought in Palestinian artists to do designs. Some also made separate posters on their own.

For Palestine - Palestinian National Fund

Poster by Ismail Shammout, 1965

via Palestine Poster Project

Palestine Liberation Army Is A School

Poster by Abboud, 1965

via Palestine Poster Project

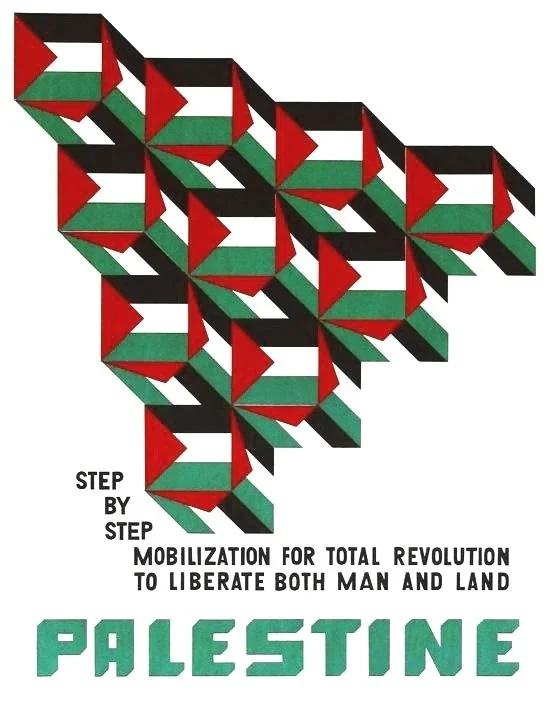

Step By Step

Poster by Samia Halaby, 1970

via Palestine Poster Project

Solidarity - Vietnam - Palestine - Rhodesia - South Africa - Latin America - GUPS (General Union of Palestinian Students)

Poster by Kamal Boullata, 1969

via Palestine Poster Project

1968’s Battle of al-Karama

Artist unknown, 1968

via Palestine Poster Project

Toiling Arab Masses

PFLP Poster by Vladimir Tamari, 1970

* Tamari also designed the PFLP logo, which Ghassan Kanafani gave his stamp of approval

via Palestine Poster Project

Even Ghassan Kanafani designed some of his own posters for the PFLP.

For the feyadeen that appeared in many posters of this initial period, Kanafani wanted to make it clear they were not terrorists but rather freedom fighters.

Shattered the Fascist Tanks

PFLP poster by Ghassan Kanafani, 1970

via Palestine Poster Project

Steadfastness of Gaza

PFLP poster by Ghassan Kanafani, 1970

via Palestine Poster Project

Variations in Expression

There were a mixture of artists trying other techniques and styles, such as a young Naji al-Ali, but there was one woman who stood out in particular.

Juliana Seraphim was 14-years-old during the ‘48 Nakba, when her family came to Beirut. They were able to attain Lebanese citizenship, which was not common with other refugees.

After turning 18, she worked as a secretary at UNRWA. At the same time, she took evening art classes with Lebanese painter Jean Khalifé, who later set up Seraphim’s first exhibition in his own studio.

She also spent time studying at the Lebanese Academy of Fine Arts and in 1959 before spending a year each in Florence, Italy and Madrid, Spain – after which she came back to Beirut. In 1961, she participated in the first exhibit at the Sursock Museum, Lebanon’s first contempoary art museum.

Painting by Juliana Seraphim, year unknown

In particular, her intention was different from the art of Ismail Shammout and others who wanted to specifically tackle the Palestinian liberation cause in their work and communicate to the masses.

Instead, Seraphim chose to use art as a medium for self-discovery and revelation. She once said: “I do not differentiate between art and life. Through art I find love, and through love I find my freedom.”

While she did not address Palestine more explicitly in her work, she did however still draw on inspiration of experiences from her childhood. In particular, she had strong memories of the Mediterranean Sea by Jaffa, where she grew up, or her grandfather’s home in Al Quds.

Painting by Juliana Seraphim, 1964

Her surrealist work was filled with dream-like imagery that had themes tied to spirituality, nature, sexuality, and more. The ‘60s were just the beginning, as her already recognizable style started to evolve further in the upcoming decades.

Painting by Juliana Seraphim, 1960

Lack of Moving Images

After Palestinian cinema had started to get its footing in the 1930’s and 40’s, that quickly came to a halt in 1948.

The time from Nakba to Naksa, ‘48 - ‘67, is looked at as the “Epoch of Silence” for Palestinian films.

However, refugees in exile did make and contribute to other films. This included the first two Jordanian feature films. Ibrahim Hassan Sirhan created Sira' fi Jerash (Struggle in Jerash) in 1957 and Abdallah Ka’Wash made Watani Habibi (My Beloved Country) in 1964.

Naksa: Further Occupation

1967 - 1970

Mostly historical information to help provide some context around how the years after the Nakba in 1948 led to the Naksa in 1967 – and the first few years that followed. Plus, some art developments after the initial impact.

A Palestinian figure looks on at the land sometime after the Nakba, undated

Photo via UNRWA archive

The Decades Leading Up To 1968

For the 750,000 Palestinian refugees from the Nakba, many hoped to come back to their homeland. After all, UN Resolution 194 had affirmed the refugees’ right of return under international law.

However, that right of return would not be honored by the occupiers. Not only that, a law by the new “state” was passed in 1950 to give the right for Jews and their spouses to come to Israel and acquire citizenship if they had one or more Jewish grandparent.

For Palestinians, they could not come back to their homeland. Anyone who tried also faced grave danger. Between 1949 and 1956 alone, Israeli soldiers shot several thousands of Palestinians who continued to try to cross the border back into their own country. However, some managed to be able to sneak in, raising the Palestinian Arab population by an increase of about 30% again in the early 1950s.

One of the first kindergarten classes in Dikwaneh camp, Lebanon, directly after the 1948 Nakba

Photo via UNRWA archive

For those who had stayed in their homeland after the Nakba in ‘48, they were supposed to be treated as citizens with full rights. However, the Israeli imposed a military rule over Arabs, using discrimination to keep strict control over movement of people and organization, including striking down any efforts to resist repressive policies. Any independent collective action – public, social, or cultural – was banned.

Palestinian Arabs were also isolated in select villages and towns as the Israeli miliary aimed to take over more land. In 1959, some of the restrictions slightly lessened as the Zionist occupiers needed more workers they could cheaply pay, which required an increase in freedom of movement.

Young women play basketball at the Women's Activity Centre in Kalandia, West Bank, 1950s

Photo via UNRWA archive

Arabs were treated as inferior, with limited rights. Israeli military permission was needed for anything from education to health care to commerce, and even marriage or divorce. Israel controlled their life with a strict occupation.

And for those in exile, refugee camps were difficult as well. As UNRWA notes: “The lives of the refugees were turned upside down; they were faced with disease, lack of food and water, life in unfamiliar places and overcrowding.”

Palestinian refugees arrive in East Jordan, 1968

Photo via UNRWA archive, by George Nehmeh

Fighting for Liberation

Israeli Occupation Forces continued massacres of Palestinian Arabs in the country.

In 1953, for example, massacres included attacks on Qibya in the West Bank and al-Bureij refugee camp in Gaza – leaving over 100 Palestinian martyrs in the process.

Israeli soldiers would keep targeting these areas in the years that followed, like in 1956 when hundreds of Palestinians were martyred in Gaza during Israeli attacks in Khan Yunis and Rafah.

A depiction of a 1956 Israeli massacre in Khan Yunis, Gaza, on November 3, when hundreds were martyred by Israeli soldiers

Painting by Tamal Al-Akhal later in 1963

via @atlajala

Organizations like the UN Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) continued to provide assistance on certain levels – such as with shelter, food, medical aid, education, work programs, and more – but it didn’t change the fact that there was a military occupation.

Palestinian students in the Auto Mechanics course at UNRWA's vocational center in Gaza, undated

Photo via UNRWA archive

In order to combat continued Israeli aggression, Palestinian armed resistance fighters – otherwise referred to as “fedayeen” at this time – formed paramilitary groups around the early 1950s to be able to defend their people and homeland.

This also evolved into a more formal Palestinian fighting organization that would be independent from Arab governments. Thus, Fatah was born in the late 1950s, its name an Arabic acronym in reverse for “Harakat al-tahrir al-watani al-Filastini” which translated to “The Palestinian National Liberation Movement” as part of its self-declared mission. Yasser Arafat was one of its founders. As The Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question notes:

“Fatah was the first national liberation movement since 1948 to be started by Palestinians themselves and that brought together Palestinian activists from different ideological and intellectual backgrounds. It called on all politically active Palestinians to abandon their party affiliations and to be united under its banner as a movement to ‘organize a vanguard that would rise above factionalism, whims and leanings to include the entire people.’

The Arab nationalist slogan prevalent at the time was ‘Arab unity is the path to the liberation of Palestine.’ Fatah reversed it, contending that ‘the liberation of Palestine is the road to Arab unity’; it acknowledged the pan-Arab dimension of the Palestinian cause but insisted that the Palestinian people had to rely on themselves in their struggle for liberation. For Fatah, the Palestinian revolution would be ‘Palestine in origin and (pan) Arab in its development.’

The movement's leadership saw armed struggle as its primary means of liberating Palestine. It modeled itself after the revolutionary struggles in Algeria, Cuba, and Vietnam.”

الكرامة ١٩٦٨ (Dignity, 1968)

Poster for Fatah

Designed by Al Muhandis Shukri, 1968

via Palestine Poster Project

Revolution Until Victory

Poster for Fatah

Designed by Kamal Boullata, 1969

via Palestine Poster Project

Cells of Fatah began to form in Gaza – but also in Jordan, Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, Kuwait, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia.

At the same time, there was also an interest by others to create a Palestinian political entity. This came to fruition with the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) after a Palestinian National Congress was called in June 1964.

The PLO was officially recognized at the second Arab summit that September, though with the explicit agreement they would not try to arm Palestinians in Jordan or attempt to gain sovereignty from Jordan in the West Bank.

“The establishment of the PLO prompted Fatah in particular to accelerate the consolidation of its presence on the ground, by establishing its military wing, al-Asifa (the Storm), and launching its first military operations in January 1965,” notes The Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question.

One of the several West Bank refugee camps in the 1950s

Photo via UNRWA archive

1968 Naksa

Since the Nakba in 1948, Israel had continued to fight against the neighboring Arab countries – especially since the West Bank was under Jordanian sovereignty and the Gaza strip under Egyptian sovereignty.

This included attacks against in Egypt in 1956 (with Britain and France as Israel’s allies) and diverting the Jordan River in 1963 (with Syria as Jordan’s ally).

In June 1967, Israel started a new stage by launching a surprise attack on Egypt. More attacks followed that were primarily against Jordan, Syria, as well as within Palestine.

In what is sometimes referred to as the Six-Day War, Israeli Occupation Forces took control of the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and the Gaza Strip. They also took control of the Sinai Peninsula from Egypt and the Golan Heights from Syria.

This became known as Al-Naksa, which translates to the setback.

Israeli Occupation Forces driving towards the Dome of the Rock at Al-Aqsa Mosque in 1967

Photo via Getty Images

The Naksa displaced another 300,000 Palestinians from their homes – including some who had already been expelled during the Nakba – bringing the total to over a million Palestinians driven out of their homes between 1948 and 1967.

The overwhelming majority of the newly displaced Palestinians sought refuge in Jordan. Many crossed into Jordan through the river, and did so on foot with very few belongings.

Palestinians forcibly displaced across the Jordan river on the damaged Allenby Bridge in 1967

Photo via UNRWA archive

The size of land that now made up “Israel” had significantly grown and the entire historical Palestine territory had now been seized. On the eve of the initial June 5 attack, Israeli Labor minister Yigal Allon wrote: “We must avoid the historic mistake of the War of Independence (1948)… and must not cease fighting until we achieve total victory, the territorial fulfillment of the Land of Israel.”

Their intention was clear: to fully take control of all the land, so there could be no Arab sovereignty in any territory. The Zionist mission to establish a so-called “Jewish state” at the harm of the local Palestinian Arab population was in full force.

صمت البحر

(Silence of the sea)

Artwork by Abed Abdi, 1969

Immediately after, UN Resolution 242 called for a withdrawal of Israeli forces from territories occupied during this battle, among other requests.

Israel not only ignored the UN, but they actively encouraged and supported Zionist settlers to move into these areas, building homes on land they did not own. This went directly against international law.

They also illegally annexed East Jerusalem and different parts of the West Bank, which they self-deemed part of the “state of Israel” – which was not recognized as true by the internal community.

The feyadeen resistance fighters who had already formed became even more determined in armed struggle, feeling a heightened need to take Palestine back as there was insufficient help from the rest of the Arab world or extended international community.

The Halo

Painting by Ismail Shammout, 1969

via artist archive

As The Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question writes:

“The defeat brought about the realization that counting on the Arab regular armies was unrealistic and that the Arab governmental approach exemplified by the creation of a PLO of notables was unlikely to yield positive results. The Palestinian national struggle was liberated from the bonds of official Arab sponsorship.

The phenomenon of guerrilla action became widespread, and new Palestinian organizations were formed. The fierce resistance demonstrated by the Palestinian fighters and the relatively heavy losses suffered by the Israeli army in the Battle of al-Karama in March 1968 significantly boosted the movement, leading to the enrollment of thousands of Palestinian (and Arab) volunteers and setting the stage for the transfer of PLO leadership into the hands of the guerrilla organizations, especially the most powerful among them, Fatah.

This was achieved at the fourth session of the PNC, held in Cairo from 10 to 17 July 1968. There a new Palestine National Charter was approved, devoted to Palestinian nationalist (rather than pan-Arab) ideas. The fifth PNC session, held in Cairo in early February 1969, further solidified this trend with the election of Fatah leader Yasir Arafat as chairman of the PLO Executive Committee, a position he was to hold until his death in 2004.”

In addition to Fatah taking the lead of the PLO after the defeat in 1967, other factions also continued to pursue their efforts. The Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) was also formally organized around this time and initially became a faction of the PLO in the late 1960s. The group itself split soon after, and the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine (DFLP) was born from the separation of members due to differences in strategy.

Art featuring a split rendition of the Dome of The Rock and featuring Arabic text

by Jordanian ceramicist Mahmoud Taha, in support of Palestine

Amman’s Refugee Art Community

The 1967 events only further pushed artists to get more serious – both in Palestine and in neighboring countries – to make work about the Palestinian struggle.

Amman, Jordan – where many displaced from the Naksa fled – then also became a home and center for Palestinian artists in exile. It didn’t take long for there to be exhibitions with themes of liberation, appearing in Amman as soon as 1968.

Jordanian ceramist Mahmoud Taha said that "it was not possible to show artwork that had no connection to the movement.”

A 1969 exhibit in Amman, making the Battle of Al Karameh from the previous year, featured many types of art – children's drawings, photographs, paintings, sculptures, maps, prints, books, records, songs of the revolution, stamps, clothes, and more. It featured artists from all over the Arab world and other international countries.

Beirut and Amman both played important roles during this time for those displaced outside of the country.

Palestinian refugee children play outside their tent school in Ghor Nimrin camp, Jordan

Photo via UNRWA aarchive

In Palestine, with the homeland entirely taken over, there was one shift in particular that impacted artist relations. Those in Gaza and the West Bank and previously been unable to have contact with those in the territories taken over as part of the ‘47 UN Partition and ‘48 Nakba. However, once again, artists across all these areas were able to have communication, for the time being.

Palestine Film Unit

After establishing the Art Department of the PLO in 1965, there were more additions to come.

The Palestine Film Unit (PFU) came in 1967 to make films that took back the narrative into their own voice. The goal was to document the revolution and create a historical archive.

It was done in conjunction with Fatah, making it the first cinema unit working under a Palestinian military organization.

Sulafa Jadallah and Hani Jawharieh at the Battle of Al Karameh in 1968

Photographer unknown

Leading this department were filmmakers Mustafa Abu Ali, Hani Jawharieh, and Sulafa Jadallah.

Mustafa Abu Ali had just graduated in 1967 after studying in the US and UK. He stated at the time that “the Palestinian resistance believes that action through cinema is a natural extension of armed action.”

Sulafa Jadallah had also studied, but closer to home. She was the first woman admitted to the Higher Institute of Cinema in Cairo, where she excelled. Jadallah is also referred to as the first female cinematographer in the Arab world in general.

Jadallah’s impact was significant, but her career was cut short in the middle of 1969 when she was unfortunately hit by friendly fire. She survived but was unfortunately paralyzed, never able to shoot a film again.

Photo by Film Unit leader Hani Jawharieh

Hani Jawharieh was involved with both the Film Unit as well as the PLO Photography archive.

Samia Halaby writes about his role in her book, Liberation Art of Palestine:

“Jawharieh was the first photographer to accompany Palestinian freedom fighters to the Jordan River Valley during the late 60s.

In 1967 he created a film called Exodus (different from the American film of the same name), which told of the evictions of the Palestinians from their homes and lands during the war of that same year.

Many of the films, which he made in Jordan just before leaving to Beirut, document the destruction by Israel of agricultural lands in the Jordan Valley. These films were followed by a series of films and photographs documenting the life and struggle of the Palestinian refugee.”

In 1970, filmmaker Jean Luc-Godard – a pioneer of the French New Wave movement – traveled to Amman, Jordan to spend time with their team at Palestinian refugee camps. While there, he and colleague Jean-Pierre Gorin also captured footage that was supposed to be a film about feyadeen.

However, Black September – otherwise known as the Jordanian Civil War between Jordan and the PLO – led to mass casualties. This included many of the fighters who had been the focus of Godard’s documentary, and he ultimately abandoned the project. (The footage was later re-purposed in his experimental film Ici et ailleurs, or Here and Elsewhere.)

Still from Jean-Luc Godard’s footage of Palestinian feyadeen

With the Film Unit, “After the horrific events of Black September, Mustafa Abu Ali, along with the rest of the PLO left Jordan and went to Beirut. Hani Jawharia and Sulafa Jadallah were (at the time) unable to get out of Jordan,” wrote Emily Jacir in a later article for The Electronic Intifada.

Artists Get Organized

1970 - 1980

A prolific decade of art by both Palestinians and those in solidarity of the cause, with many important efforts that tried to bring artists together and people together.

Rabita / The League of Palestinian Artists

After the growing unity among artists during the end of the 1960s, there was an effort to more formally organize together. An artist association was established in 1973 by a group of artists that included Sliman Mansour, Nabil Anani, Isam Badr, and more.

Samia Halaby refers to this group as the Rabita (رابطة), while Kamal Boullata and others call it The League of Palestinian Artists. (While both names apply, Rabita will be the name used below.)

Jamal al-Mahamel (Camel of Hardship)

Painting by Sliman Mansour, 1973

Printed as a poster in 1975 and 1980

via artist archive

Palestinian painter Sliman Mansour was born in 1947 and spent his childhood in Bethlehem and Al Quds, then under Jordanian sovereignty after the 1948 Nakba.

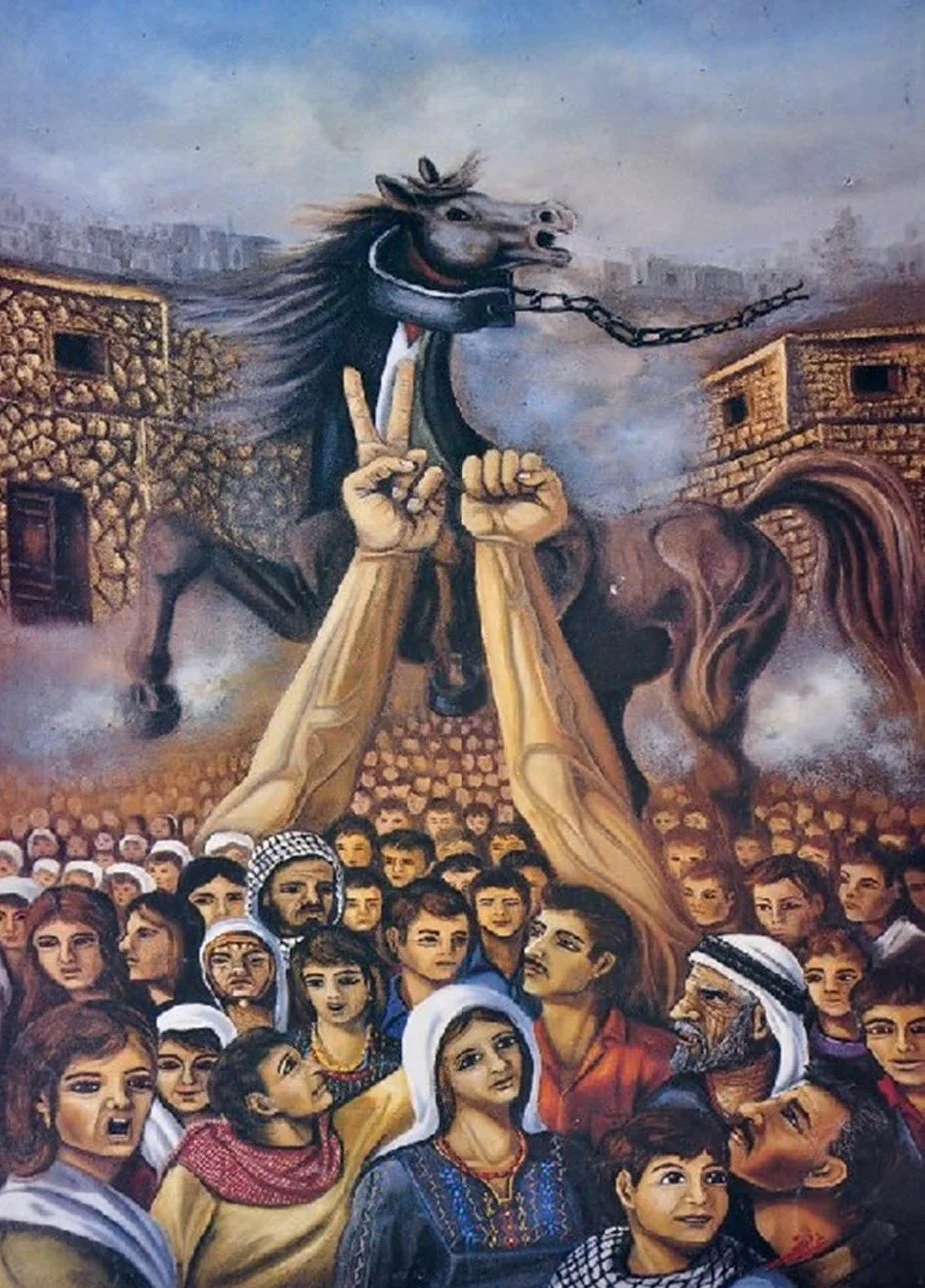

Mansour excelled in art from a young age and was planning to go abroad for art school. After the 1967 Naksa where Israeli forces seized the West Bank, however, he was exposed to a greater understanding about Palestinian history and stories. This greatly influenced the work Mansour would soon make, incorporating symbols of Palestinian identity.

For the Rabita overall, they felt that accessibility was important. So they took their art and utilized the easy production of posters to be able to efficiently spread the work, just as the PLO and others had adopted. Mansour says the united artists shared common themes often integrated across the group – including prisoners, martyrs, the Earth, Al Quds, land confiscation, eviction, sumud, and roots.

In her book Liberation Art of Palestine, Samia Halaby says that the Rabita were also intentional about how they captured these ideas, making sure to emphasize Palestinian history and culture.

Palestinian artists painting a landscape of Ras Karkar (West Bank)