Mahmoud Al-Shaer

Mahmoud Alshaer is a 35-year-old poet, writer, cultural curator, father, and husband.

He served as the Executive Director and Editor-in-Chief of Majalla 28 (aka 28 Magazine), an independent literary and cultural platform he co-founded in 2014 to amplify emerging Palestinian voices.

Mahmoud also led Gallery 28, a community library in Rafah that focused on Palestinian literature and cultural production. They welcomed both writers and artists by hosting exhibitions, concerts, and readings. The building was destroyed by the IOF in May 2024. However, he and his co-founder kept it going through the genocide, including collaborating with ArabLit on their Spring 2024 issue.

In addition, he has also worked as the Cultural Program Coordinator at Al Ghussein Cultural House, in Gaza’s old city.

During the genocide, Mahmoud and his family have been displaced several times. One of his two children – his son, Nai – was evacuated to Turkey with Mahmoud’s mother in November 2023. This has made it even more difficult for the family to be separated for this long. Through it all, he’s continued to write.

Mahmoud’s personal writings have been published several times this year – Letters from Gaza, I Am Still Alive, and A Year on the Abyss of Genocide.

“For two years I have lived under genocide, breathing in a cellar of impossibilities—impossibilities too large to believe. Entire cities vanish. Tents become makeshift salons; rubble turns into a living room. Everything defies reason.”

Read writing from Mahmoud

I Don't Want to Forget Who I am

This is who I am now: a body carrying memories that words cannot fully contain, a soul adrift, searching for meaning amidst the rubble.

Which memories should I keep close to my heart? Should I cling to the life we lived under siege, before the onslaught of this war of extermination? Or should I embrace the memories forged in the fire of this war? Which are more vital? The pain is so deep, it’s hard to tell which of my emotions are still mine, untouched, and which have been twisted by the horrors of this genocide.

I dream of standing on a small stage in a quiet place—perhaps in the warmth of Gallery 28, within the historic walls of Al Ghussein cultural house, in the open-air courtyard of the Press House, or in the multi-purpose hall of the Qattan Cultural Center. I long to open one of 28 Magazine’s events in these cherished spaces, to stand before my friends and the community that fills my heart, to watch as poets and artists breathe life into their works—poetry, music, paintings, films—sharing them with the people they love.

I dream of returning home in the evening, to find Majd, Nai, Hadil, and my mother waiting for me. All of them, safe and whole, their laughter filling the air, their presence a balm to my soul.

This is who I am now: a body carrying memories that words cannot fully contain, a soul adrift, searching for meaning.

What do I want to write about? I’ve always feared the weight of writing, the way it forces you to confront your brokenness. I’ve claimed to live in a state of poetry, but have I truly written it? I don’t want to remain silent, but I don’t know where to begin. Should I write about my mother’s and my son Majd’s journey to Turkey, about how I didn’t realize their absence would stretch into nine long months, with no end in sight? Can I even begin to capture the pain of a farewell that never happened?

I was born on April 24, 1990, and my father was taken from me on October 23, 1990, by the bullets of Israeli settlers at the border of the Gaza Strip.

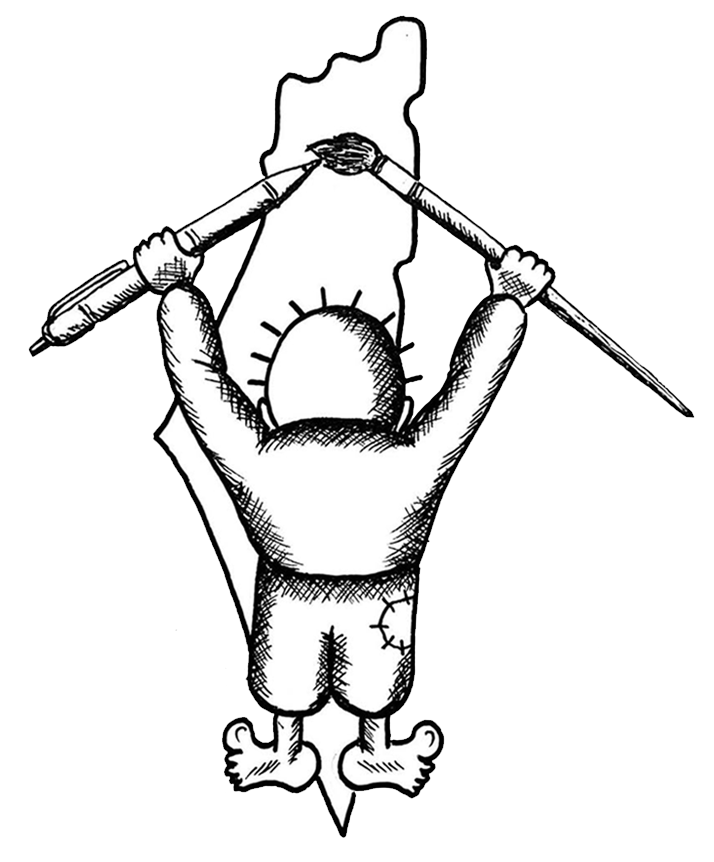

Majd and Nai were born on October 11, 2021—too soon, at just 31 weeks. For four weeks, they fought for life in the incubator before they could finally come home. Our celebration of their survival was immense, far greater than any other family’s celebration of a new birth in our neighborhood. In those first six months, my experience with my children illuminated the places and moments that I never knew I had with my father.

For nine months, I’ve been redefining my father’s absence through my understanding of what Majd misses from me. And I say understanding because I still have Nai—his twin—beside me. I can see so clearly the difference between Nai’s life with me and Majd’s life without me. Now, I fully grasp the depth of what was stolen from me when those settlers’ bullets took my father from my life.

This is who I am now: a body carrying memories that words cannot fully contain, a soul adrift, searching for meaning.

The despair caused by the length of this genocide forces me to confront losses I had previously refused to acknowledge, like the killing of many friends and relatives, and the loss of all our cultural spaces, both public and private, that had formed a cultural scene despite the siege imposed since 2006…

The despair caused by the length of this genocide pushes me to confess my desire to survive. My desire for times not threatened by the constant sound of warplanes flying above us. My desire to walk without fearing being targeted. My desire to sleep without panic.

The despair caused by the length of this genocide makes me long for the sound of cars and people in the center of Rafah on Saturdays, the weekly market day. I long for the days when that hustle and bustle used to frustrate me.

I am here. I have been here, on this land that never stops redefining its meaning—and my relationship to it, to my family, to my people. Each dawn in this place is another attempt to become what I have not yet been, and what I still hope to be.

I can no longer return to who I was. None of us can. I carry in my face the traces of those who are gone; in my voice, the echoes of those beneath the rubble. This is how, metaphorically, I recover my return.

I know now that the only right worth celebrating is our right to life itself—my life, which I almost forget as I search for definitions far from home. I don’t need more lamentation, or empty praise. What I need is to bind my culture to life, to guard my memory from erasure, to tell my own story.

The genocide has pushed me back to my first questions: What does it mean to write? To dream? To remain human among walls of death?

I did not choose this road. I am not a hero, nor an eternal victim. I want to be an ordinary person, able to love, to create, to live a simple life in a simple homeland.

I don’t want to glorify either heroism or victimhood. I want to return to the origin of the story: an ordinary human being, alive, capable of making meaning in a life worth living.

Next week, on October 11, my twins, Majd and Nai, will turn four.

Once again, there will be two birthday cakes—one in Al-Mawasi, and one in Turkey. A celebration divided by borders, by war, by everything that should never separate a family. Yet even in this painful distance, I hold on to the small light that keeps us together: love, memory, and the hope that next time the same candle will shine on same cake.

Read more of Mahmoud’s work:

Pen/OPP — “Letters to Oraib”

Discover more Gaza writers & artists

Follow the links below to see a list of other creative individuals in the Strip to support and amplify.