Rosalind Nashashibi’s Short Films of Palestine

The filmmaker Rosalind Nashashibi was born in London to a Palestinian father and Irish mother. “What I got from both my parents' backgrounds was conflict, and a desire they both had for something different that could be found elsewhere.”

For a while when she was a kid, Rosalind’s family would take frequent trips to Palestine and visit relatives.

However, she says, “My Palestinian identity was always there, but wasn't something that was really discussed… It wasn't a happy or easy conversation and there was a lot we didn't know as kids, and too many pitfalls we could fall into. However, it made my childhood different from the rest of the community I grew up in.”

As she got older, as part of her multifaceted career as a filmmaker and painter, she began to make some short films connected to her father’s side. In her work, the camera is very observational. Her editing is gracious, allowing her subjects to breathe, and focusing most of all on everyday simple moments.

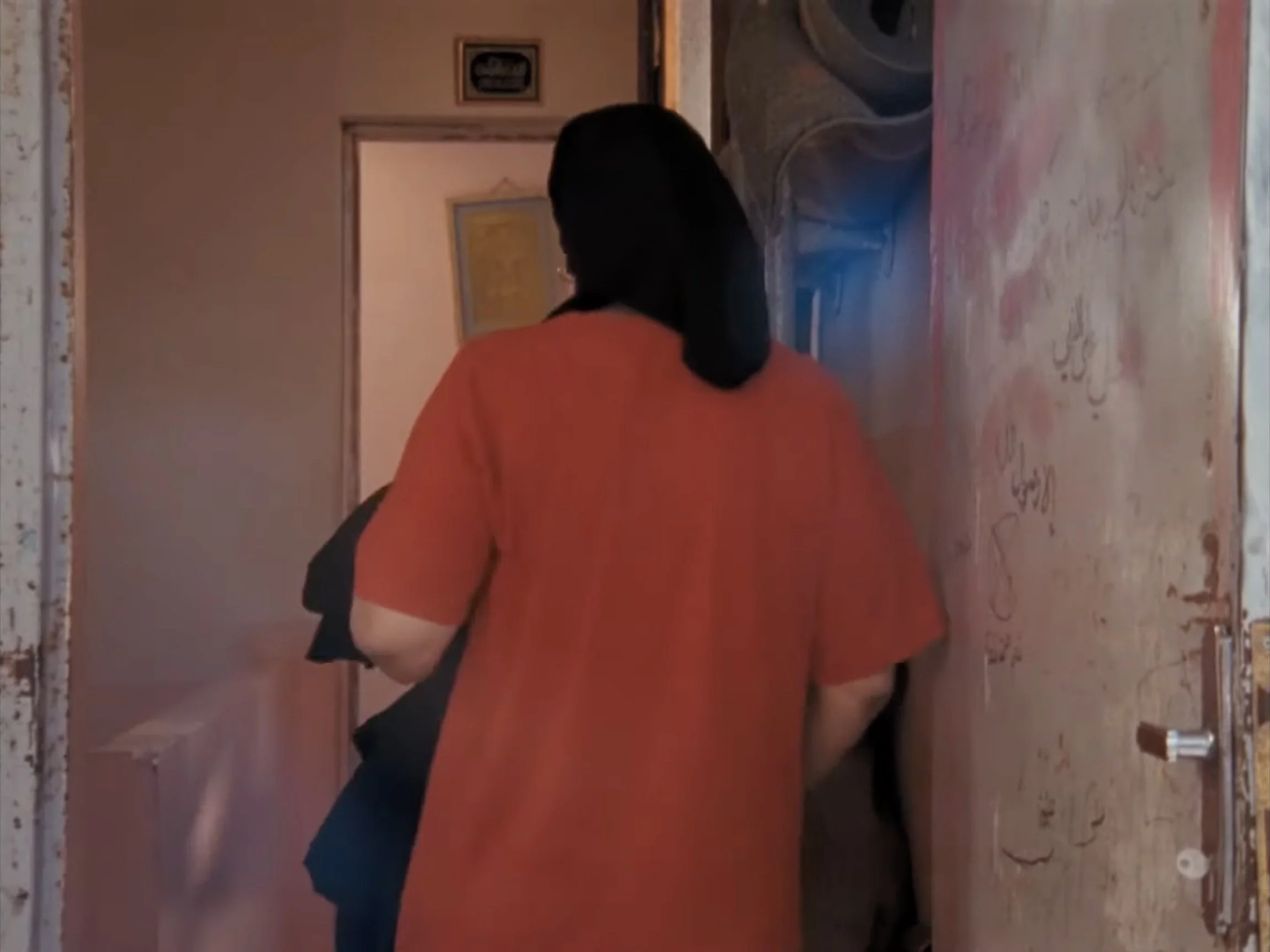

Dahiet Al Bareed, District of the Post Office (2002)

During her trips to Palestine as a kid, Nashashibi would go to a special area called Dahiet al Bareed, otherwise known as District of the Post Office.

For one, it was where it was her father grew up. But more incredibly, the town was actually conceived and built by her grandfather, who had ran the Palestinian Post Office. “It was a kind of utopia in a way because they ran and owned their own neighborhood where everybody knew each other,” she said.

This neighborhood used to be part of Al Quds / Jerusalem, and then became technically an area between occupied East Jerusalem and Ramallah.

As an adult, Nashashibi later went back to see how it had changed. “I found it to be surrounded by this kind of sprawl and for various political reasons to do with people being urged to move out of the Old City and coming in from other parts of the West Bank, it had turned into this quite chaotic, very quickly built-up, quite squalid area, where there was no real rule — a kind of no-man’s land,” she said.

The area itself eventually floated in kind of a no-man’s land, essentially. “It is technically West Bank but it has never been under the control of the Palestinian Authority — it’s under the administrative division of the Israeli military. Nobody was really looking after the place so the kids seemed to be ruling the streets. A place defined by the checkpoint down the road and its position as neither Occupied Territory nor the West Bank.”

She ended up making a film about it – the self-titled Dahiet Al Bareed, District of the Post Office (2002) – simply documenting moments of everyday life in the town. It is one several short films Nashashibi’s done on Palestine, to date, which are the focus of this feature.

Dahiet Al Bareed, District of the Post Office (2002)

Dahiet Al Bareed, District of the Post Office (2002)

Dahiet Al Bareed, District of the Post Office (2002)

Dahiet Al Bareed, District of the Post Office (2002)

A couple of years later, Nashashibi made another film in Palestine, Hreash House (2004).

Inspired by visiting a family friend in Al-Nasirah (Nazareth), she wanted to capture the collective living and community inside this one home. She ended up filming it over four weeks, including a big dinner during Ramadan.

''My father grew up in that situation,'' Nashashibi said about the film. ''My mother also grew up in an extended family in Belfast, and she talked about it a lot, what she had that we didn't have: big family dinners that went on for ages, big discussions around the table. I didn't have that when I grew up. Most of the world is still structured like that, although it is changing; the extended family has a much larger significance than just Palestinians or Arabs.''

Hreash House (2004)

Hreash House (2004)

Hreash House (2004)

Hreash House (2004)

Hreash House (2004)

Hreash House (2004)

In this short, you can also see Nashashibi’s fascination with the details of colors and patterns.

Hreash House (2004)

Hreash House (2004)

Hreash House (2004)

A decade later, in 2014, Nashashibi filmed what would become Electrical Gaza (2015). The footage captures everyday moments in Gaza, similar in its observational eye.

The Gaza Strip was occupied in 1967 by Israeli Occupation Forces (IOF), along with the West Bank. In 2005, the IOF withdrew military forces but maintained an air, sea, and land blockade. This became what has been described – by the Human Rights Watch, among others – as making Gaza an “open-air prison.”

The withdrawal of troops of course did not stop further military invasions and offensives on Gaza in the years to come, such as in 2008-09 and 2012.

It took Nashashibi a long time to get permission to film there, but eventually she did. She began in 2014, but the area was being bombed the first night she was there. After only being there for a week, the British Foreign Office called and encouraged her to leave for safety. It would be the start of another Israeli offensive over 50 days that summer.

Electrical Gaza (2015) is available to stream in the player above. (18 minutes)

Similarly to a film like Jenin, Jenin, there is no external exposition to explain what is happening or any context around the circumstances. Instead, it provides a world to be immersed in that people being their own context to.

Electrical Gaza’s lack of a narrative arc is consistent with Nashashibi’s first two short films in Palestine. The wandering and lingering eye of the camera is the focus, as she is finding the film along the way.

In a thoughtful piece from Minou Norouzi, On Discomfort & Empathy In Rosalind Nashashibi’s Electrical Gaza, she argues the observational footage may seem ambivalent, but it’s more than that. While some may feel the film should take a clear loud stance and even feel discomfort from the lack of acknowledgement, Norouzi argues that this is actually the point and the “refusal to deliver catastrophe must be read as intentional.”

“Nashashibi refuses to engage viewers with representations of suffering of the distant (Palestinian) others and offers a visual counter-narrative to Palestinian lives that are otherwise handled in news media and documentaries as ‘humanitarian commodities’…

(Her) films share attentiveness to the pleasure of simply looking, the representation of which is not preoccupied with securing meaning but remains opaque. This can be discomforting to some viewers, especially when the topic of exploration is as politically contested as is the question of justice relating to Palestine and Palestinian people.

But Electrical Gaza requires a suspension of the expectant impulse for it to make visible, inform, educate, and campaign to give space to ‘the pleasure of the real’ as it communicates itself on its own terms.”

In addition, the nature of the film not only invites but essentially demands for viewers to be part of the process, to bring their own meaning and understanding that the film can take the shape of.

“This intended process of co-creation, it is hoped, opens to viewers the possibility of reflecting on their position of safety as viewers and the complicity in so-called world-making that accompanies this process… This places the ethical obligation of reading and interpreting the images in direct relation to viewers responsibilities towards the conditions that produce the lives depicted.”

Electrical Gaza (2004)

Electrical Gaza (2004)

Electrical Gaza (2004)

Electrical Gaza (2004)

The viewer’s knowledge of the reality in Gaza accompanies seeing the embrace of joy, of life, despite the occupation, blockade, and siege.

This includes moments of young boys with horses playing in the saturated blue water of the Mediterranean sea, or three men simply sitting around enjoying each other’s company at one’s home and making food.

Electrical Gaza (2004)

Beauty also comes in the visuals themselves. As is typical of Nashashibi’s projects, it was shot on 16mm film in a 4:3 aspect ratio, which adds to the timeless feel. There is a clear eye for composition, light, colors, and human expression.

Viewers also see gliding, panoramic shots that capture both crowds of people and aerial views of the city.

One can imagine the even wider array of footage she would have captured if it would have not been for the 2014 attacks.

The fact that Gaza is under consistent attack – and that this is not surprising for Nashaashibi to have encountered – is, of course, part of the collective knowledge and history that viewers bring to the story.

A main location that comes up repeatedly is the Rafah crossing, where Gaza borders on Egypt, showing just one example of the control over airspace, waters, and borders.

Electrical Gaza (2004)

Electrical Gaza (2004)

Electrical Gaza (2004)

Electrical Gaza (2004)

The short also contains brief animation sequences that are sprinkled in, reflecting scenes from the actual film.

Sometimes they are close to their companion shots, like a scene of two children in an open area with many palm trees around them.

Other times, they re-imagine the moment. An example of this happens with a shot of the Rafah crossing point. While guards stand during daylight in one real-life shot, the animation cuts to a dusk shot that’s mostly unpopulated as the Palestinian flag waves in the wind.

Electrical Gaza (2004)

At one point, a black circle appears on top of a daylight alley scene that has previously been shown. It slowly grows larger, again leaving this out-of-place moment to have its purpose - or lack thereof - determined by the viewer. Nashashibi did later say of her intention: “I used that to try to find a way to show the violence to come, and it was already in the air.”

Electrical Gaza (2004)

Electrical Gaza (2004)

Electrical Gaza (2004)

Electrical Gaza (2004)

Electrical Gaza (2004)

Electrical Gaza (2004)

Electrical Gaza (2004)

Another thing that can add to the heightened and mystical nature of the film is from the score. One scene that stands out particularly is the driving sequence around three and a half minutes in, where there’s a shot looking out a window from a moving car. The original music by Chris Evans and Morten Norbye Halvorsen that plays during this scene sets the tone for experiencing the visuals of stores, people, and cars.

This music is also accompanied by a sound design that often chooses to use natural environmental sounds to put you in the place or to emphasize certain elements. Other times, you can hear Nashashibi herself breathing, added in post-production for an intentional effect.

Electrical Gaza (2004)

Electrical Gaza (2004)

While she is most known for her films, Nashashibi is also an accomplished painter.

“While a very direct observational filmmaking took precedence over other things, I was always making collage, prints and two-dimensional works alongside film as I wanted to see light spaces in my exhibitions,” she said.

Black Soil, 2020

Painting by Rosalind Nashashibi

via GRIMM Gallery

This also gives her a balance as an artist, where film is something she does for a couple of times a year over a small but intense period. It’s very social, very collaborative. The weeks or months editing afterwards are also in the conversation of collaboration with another editor. Painting, on the other hand, is something Nashashibi can do alone and something she can do daily. She sees them as two sides of the same coin.

Salon d’Honneur, 2024

Painting by Rosalind Nashashibi

via Altman Siegel gallery

In a 2023 feature for the art platform Ocula, Nashashibi says:

“I would say my paintings and films both access more than what documentary approach can reach.

For me, it's the mix of reality and observation, with an attempt to represent something intangible, that makes paintings and film more real, or that relates it to a real experience rather than reportage.

It's about trying to record something on several layers of perception, not just those that are obviously communicable to others. That is the goal.”

Electrical Gaza (2004)

Electrical Gaza (2004)

Electrical Gaza (2004)

Electrical Gaza (2004)

Electrical Gaza (2004)

Electrical Gaza (2004)

Electrical Gaza (2004)

Electrical Gaza (2004)

Electrical Gaza (2004)

Electrical Gaza (2004)

Last Updated

2024

Artist online

Instagram @rosishibi

Images via the short films

Dahiet Al Bareed, District of the Post Office (2002)

Hreash House (2004)

Electrical Gaza (2015)

*YouTube links for first two films currently have gone inactive

VA4P will try to replace when available

Info sources

Bidoun

The Herald, Scotland

MAI: Feminism & Culture

Ocula

Turner Prize 2017