Part 4 -

Palestinian Art History

The First Intifada

1987 - 1993

A boiling point is reached as a Palestinian rebellion starts and continues across society, which artists also drew inspiration from and incorporated into their work.

Leading Up: The 20 Years After Naksa

With the West Bank and Gaza strip seized in 1967, the rest of the homeland of Palestine was under Israeli control. This led to a large influx of illegal settlers who expelled Palestinians from their land and built their own houses there instead. The government also seized area for military bases and other uses. Additionally, they built an array of roadblocks and checkpoints.

The land, however, wasn’t the only matter of subjugation. As analyst Mouin Rabbani wrote for Mondoweiss about the West Bank and Gaza:

“The occupied territories were not governed like the rest of Israel – which would have been bad enough – but rather ruled by a subsidiary military government which legislated by decree and was tailor-made to drive Palestinians out of their lands and out of their minds.

Israeli control was so pervasive and intrusive that the colonial administration bore greater similarities to totalitarian states than Israel itself.

Permits were required for virtually everything, with one benefit being a steady supply of informers and collaborators recruited amongst parents desperate to obtain medical attention for a severely ill child, university graduates eager for employment to support their existing families and start new ones, and a host of others…

Those who refused to cooperate, persisted with their thought crimes or actively resisted Israeli power with so much as a slogan could expect imprisonment, torture, the sealing or outright bulldozing of their homes and the ultimate punishment of deportation and exile.

That’s the short version, and conditions in East Jerusalem, formally annexed and under direct Israeli government control were only in some respects better while in others even worse.”

By 1987, it had been twenty years of attempts to break free of this oppressive system, which had been ultimately unsuccessful at that point in achieving the goal of liberation.

The economic reality for Palestinians in their homeland was difficult, like the rest of their lives. And those refugees in neighboring countries were still not able to come back – despite their right to return under international law – after what was, at this point, nearly 40 years after the 1948 Nakba.

With the invasion of Lebanon in 1982 that had driven out the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and weakened them, Palestinians certainly did not see the hope in that exiled political body as they previously had when it first had started. It was only a matter of time before there was a need for everyday people to take things into their own hands and not surrender to this way of life and tyrannical ruling.

Hatem Al Sesi, First Martyr of the (First) Intifada

PFLP poster by Marc Rudin aka Jihad Mansour

via Palestine Poster Project

West Bank & Gaza, Home To First Intifada

In the beginning of December 1987, there were a group of Palestinians traveling back to Gaza after their day jobs in the 1948 occupied territories of “Israel.” At the Erez checkpoint, an Isreali truck crashed into a group of cars. Four Palestinians were martyred and seven others injured. This was perceived to be not an accident but an intentional retaliation from an Israeli businessman who had been stabbed in Gaza two days prior. Several of the martyrs from that crash were residents of the Jabalia refugee camp, the largest in the country. Thousands attended the funerals later that day, which turned into protests. During the demonstration, 17-year-old Hatem al-Sisi became the first martyr of this new stage of fighting, shot after throwing a petrol bomb.

“Spreading like wildfire, these demonstrations metamorphosed into a popular revolt that within weeks made Intifada part of the English language,” says Mouin Rabbani in Mondoweiss.

Intifada – an Arabic word that translates to “shaking off” – is used in a Palestinian context to refer to an uprising. Their message was clear: Palestinians were calling for an end to the occupation. The uprising spread to every town, village, and refugee camp across Gaza and the West Bank by the beginning of 1988 – with protests filling the streets.

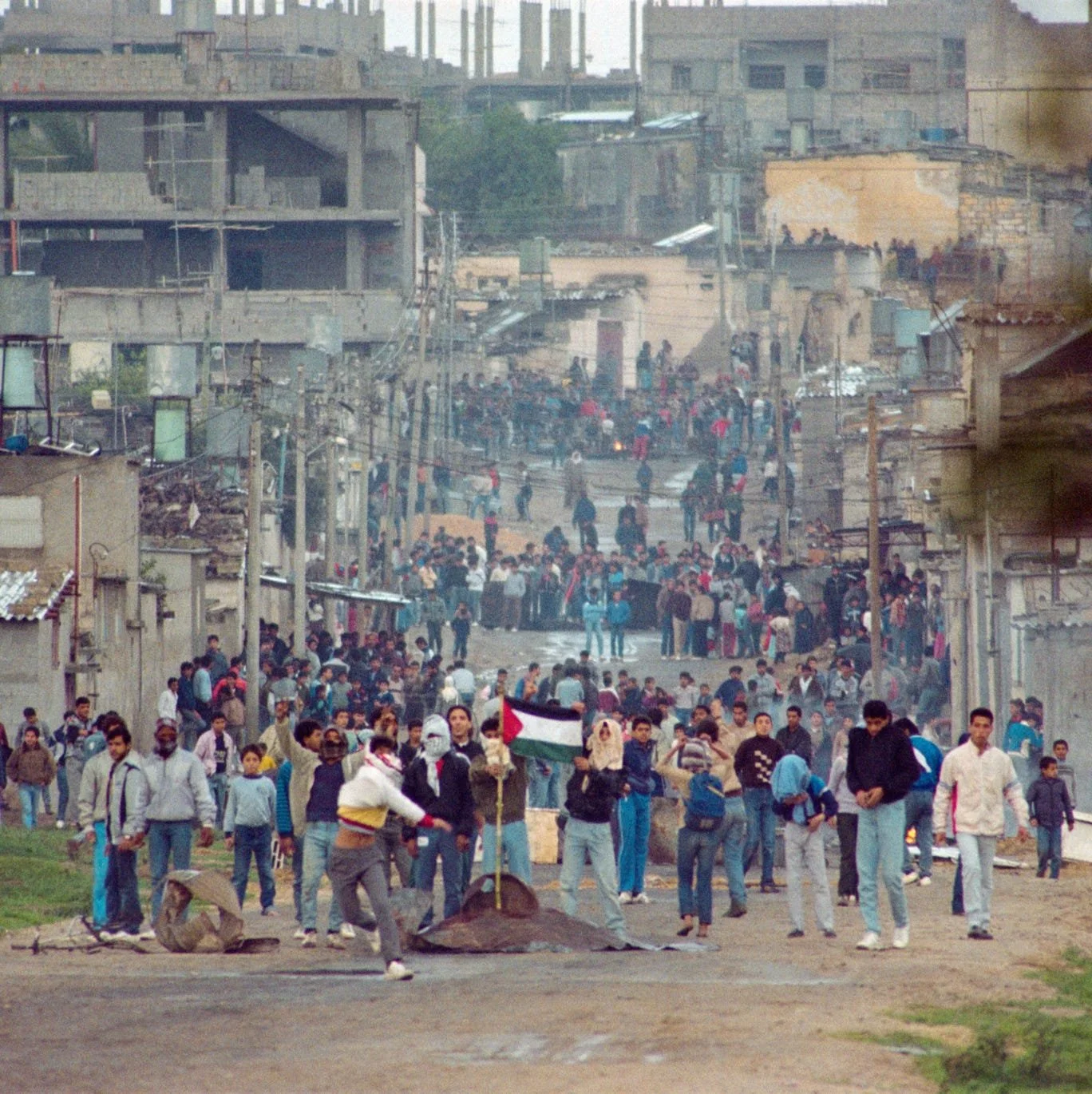

First Intifada photo by George Azar

via Al Jazeera

The Intifada was not just protests in the streets, it employed a myriad of tactics. This included incorporating both social and economic solidarity. Commercial and labor strikes were a central form of resistance during this Intifada – between business owners shutting down their stores for periods or workers refusing to go to jobs in “Israeli” territory. Students were also instructed not to go to school and instead Palestinian families organized classes in their private homes.

Certain areas took on specific measures. In Beit Sahour (West Bank), for example, residents refused to pay taxes. After all, the money they paid was not going to their own representatives – it was going to Israel, to build a more powerful army that could further oppress them. The Israeli Occupation Forces besieged the area for 30 days and raided homes, businesses, and factories who withheld tax.

A standout part of the first Intifada was young kids throwing stones and using slingshots against Israeli forces, painting a picture of a modern-day David vs. Goliath story that showed the underdog Palestinians rising up against the oppressors of Israel.

Long Live the Youth, Victory to the Uprising

Zuhdi Al Adawi poster in 1988

via Palestine Poster Project

First Intifada photo by George Azar

via Al Jazeera

Palestinian kids in 1989 throw stones in Ramallah (West Bank), as part of First Intifada

Photo by Eric Feferberg/AFP

Palestinian kids with slingshots during the First Intifada

Photo by Peter Turnley

Palestinian kids during the First Intifada

Photo by Patrick Robert

Many of these children had their hands, arms, or legs brutally beaten by soldiers, as the Israeli Defense Minister had instructed them to use ‘force, might, and beatings’ to crush protests. There were nearly 100,000 children arrested for throwing rocks over the years of the Intifada and many of whom would spend years in prison.

However, it was far from just boys or the male resistance factions. Palestinians of all ages, genders, and faiths participated in the uprising.

A Palestinian Christian woman took off her high heels as she throws stones at Israeli soldiers after Sunday Mass in Beit Sahour in the West Bank, March 1988

Photo by Esaias Baitel

Women of all ages join in throwing stones during the First Intifada

Photo by George Azar

For a small group of others, the lack of proper weapons – and, of course, an official national army – led to utilizing makeshift options such as molotov cocktails. And only around five percent of attacks were attributed to firearms.

In addition to beating people severely, Israeli soldiers used other methods such as tear gas, rubber bullets, live ammunition, and more. There were also curfews that were typically from dusk to dawn, sometimes extending into the whole day.

First Intifada

Photo by Patrick Robert

In the first year alone, there were many injuries (tens of thousands), arrests (18,000), administrative detentions (3,000), martyrs (300) deportation of alleged leaders, houses demolished (350), long-term school closings, and more.

This would only continue over the years, with attacks that included a massacre by police at Al-Aqsa Mosque in 1990, where 20 Palestinians worshipping were martyred and 150 injured on what became known as Black Monday.

After everything was said and done, the first Intifada would result in over a thousand Palestinian martyrs (a quarter of which were children) and over 100,000 injured. Over 600,000 were arrested. An additional 30,000 faced Israeli military trial.

Gaza during the First Intifada

Photo by Sven Nackstrand/AFP

Posters

The First Intifada was the last time of the unofficial ~1965-1990 poster art era was really still in full force. During this time, various artists also made posters to spread national messages.

First Intifada poster for the Democratic Cultural Action Committees, by Sliman Mansour

via Palestine Poster Project

2nd Anniversary of the Intifada

by Zuhdie Al Adawi, 1990

via Palestine Poster Project

First Intifada poster for the Palestinian Women's Organization (PWO), by Marc Rudin aka Jihad Mansour

via Palestine Poster Project

Palestine - The Sun Also Rises

Poster by Jamal Al Afghani, 1990

via Palestine Poster Project

The Jalazoon Refugee Camp

Artist unknown, 1990

via Palestine Poster Project

Proud, Defiant and Tireless

Artist unknown, 1990

via Palestine Poster Project

Uprising and Steadfastness Until Victory

Artist unknown, 1989

via Palestine Poster Project

Determined To Challenge

Artist unknown, 1989

via Palestine Poster Project

Down with the Occupation

Fathi Ghaben, 1987

via Palestine Poster Project

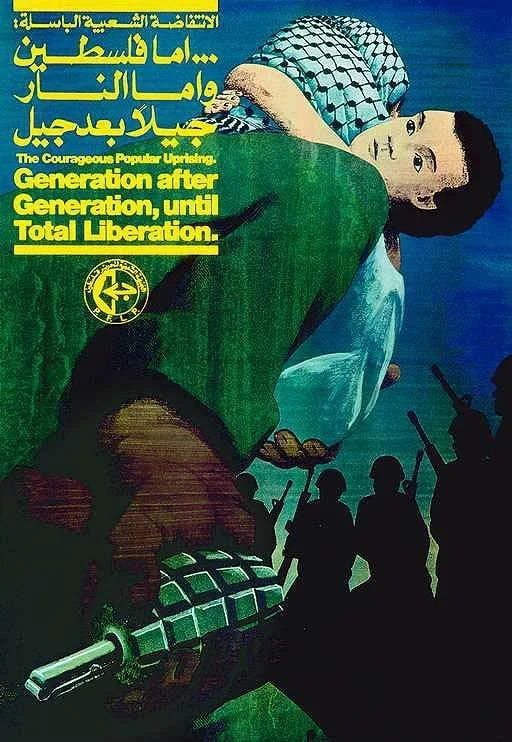

Generation After Generation

Marc Rudin aka Jihad Mansour, 1989

via Palestine Poster Project

No Voice Stronger Than the Voice of the Intifada

Artist unknown, 1988

via Palestine Poster Project

New Visions Group - Art of the Intifada

While artists did some work on posters at this time, they also took on a new artistic approach that took inspiration from the larger movement.

One aspect of the First Intifada was also the boycotting of Israeli goods. Some artists brought this into the craft and process, choosing materials natural to the Palestinian land to create art as they participated in the boycott.

A handful of artists from the Rabita, or the League of Palestinian Artists, formed a smaller group called New Visions to work under this creative path.

New Visions artists of Vera Tamari, Nabil Anani, Tayseer Barakat, and Sliman Mansour in 1988

A wide variety of natural materials and approaches were integrated, transforming the kind of work made. Some examples included:

Nabil Anani traveled to Al-Khalil, aka Hebron, to study the local craft of leatherwork.

Sliman Mansour started to use primarily mud in various forms and applications, embracing its texture and nature, and sometimes other materials like clay.

Tayseer Barakat started using wood with natural dyes, burning his images onto them. He also started using watercolors more.

Vera Tamari experimented with ceramics, as well as new and ancient postcards which she found around villages.

Nabil Anani said he had previously found his experience with oil painting limited, and didn’t realize until the first Intifada started that he gained the confidence to experiment. This freed him up and his choice of leather as a material was also tied to Islamic traditional art.

Al Khurooj Ila Al Noor (Passage into Light)

Leather and henna on wood

by Nabil Anani, 1989

via Zawyeh Gallery

Bashir Makhoul and Gordon Hon write about Anani’s experience:

“The fact that he attributes this change to the Intifada is significant because this was the moment when the struggle moved to Palestine itself, rather than being centred on the activities of exiled nationalist movements such as the PLO.

The artists, like the youths who were picking up stones from the ground to throw at armed Israeli soldiers, were looking around them for what was at hand.

The poetic symbolism of using pieces of the Palestinian ground as a weapon against its occupiers certainly was not lost on the movement and it is not surprising that it was taken up by artists.”

Isdouda

Clay, straw, henna, colored earths

by Sliman Mansour, 1987

via Palestinian Museum Digital Archive

Intifada

Mud on wood by Sliman Mansour, 1989

via artist archive

Even outside of the material change, Sliman Mansour also thought that just drawings and paintings did not do justice to the reality. "I felt that it was impossible to make drawings of the Intifada,” he said. “In reality, it was too strong.”

The lack of precision of these tools made the Intifada art take on a more abstract form. Mansour also later told The Arab Weekly:

“The intifada mainly liberated us. Our art became more expressive of ourselves and more abstract. We were no longer limited to the traditional way of doing art to please a specific public.

For example, I began working with clay and this made me engage in sculpture. I believe that was the link between traditional and modern art that the younger generation is producing now.”

صعود

Watercolour and gouache on paper

Tayseer Barakat , 1990

via Dalloul Art Foundation, Beirut

Oslo Accords

1993 - 2000

Historical context on the agreement that was presented as a solution for the “conflict” to move forward, which was doubted by many from the start. In the short term, there were some benefits to it for artists.

Leading Locally vs. From Exile

The efforts of the first Intifada were spearheaded by the freshly-formed Unified National Leadership of the Uprising (UNLU), whose communiqués led political, social, economic, and cultural strategies and messages. There were also popular committees established in villages, camps, and city neighborhoods.

The UNLU was a coalition which included representatives of PLO-affiliated groups – mainly Fatah, PFLP, DFLP, and Palestine Communist/People’s Party.

There was also Palestinian Islamic Jihad, founded earlier in the 1980s, who “organized itself around the principle that defeat of Israeli occupation and subjugation could only be achieved through armed struggle, and it sought to merge the secular and Islamist strands of the Palestinian political landscape,” as Jeremy Scahill later wrote for Drop Site News.

At the same time, 1987 saw the formation of Hamas (an Arabic acronym for Islamic Resistance Movement). They were an offshoot wing of The Muslim Brotherhood – which had started in 1928 in Egypt. Hamas started to become involved during the First Intifada and had separate communiqués, too.

Over the course of this period, many leaders from all of these different groups were deported from Palestine.

There was also the PLO, already in exile, who was caught off-guard by the First Intifada’s start and rise. From abroad, at this time in Tunisia, they tried to stay involved and use the moment for their political purposes.

The first anniversary of the martyrdom of the distinguished leader Abu Jihad (Khalil Al Wazir)

Poster by Mohammed Al Rakoui, 1989

via Palestine Poster Project

Kalil al-Wazir (also known as Abu Jihad) – a Co-Founder, top member of Fatah, and close aid of Yasser Arafat – dealt directly with UNLU and strengthened PLO connection between them. However, he was assassinated by Israel in April 1988 at his home in Tunisia.

A couple of months later in June 1988, the PLO gathered at that year’s Arab Summit.

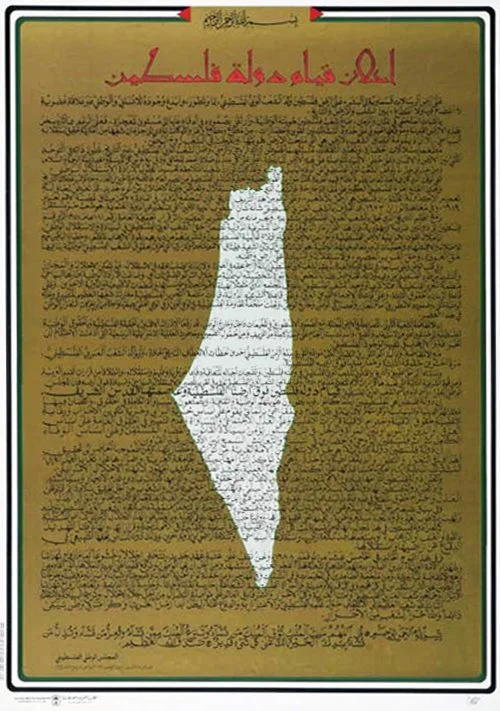

As noted in The Interactive Encyclopedia of The Palestine Question:

“Building on the political assets provided by the Intifada, and on the reactivation of diplomatic efforts to find a solution to the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, the 19th Palestine National Congress adopts two texts.

The first is the Declaration of Independence, legitimized internationally by UN General Assembly Resolution 181 and by the Palestinian right to self-determination.

The second text is a political communiqué in which the PNC states its acceptance of UN Security Council Resolutions 242 and 338 as the basis of the international peace conference, and enumerates the principles that were put forward by the Arab Summit, Algiers, 1988.”

PLO’s Declaration of Independence, 1988

Artist unknown

via Palestine Poster Project

Others like Hamas and Islamic Jihad did not align with this decision as they saw the PLO accepting the UN resolutions as concessions that gave in to Israel, ignoring the loss of land since 1948 and only focusing on what was taken in 1967. In their eyes, freedom from occupation did not only mean the West Bank and Gaza.

In 1990 during the Gulf War, Iraq invaded Kuwait and promised to evacuate on condition that Israel evacuate the occupied territories, receiving support from the PLO in the process. However, after an Iraqi defeat, it left the PLO more powerless –despite the momentum Palestinians in the homeland had built in the Intifada.

International pressure for “peace talks” built, taking more shape in 1991 at the Madrid Conference, which was organized by the US and Soviet Union. However, it wasn’t until a couple of years later that discussions grew deeper. Secret talks started in early 1993 between the PLO’s Yasser Arafat and then Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin led to a next big step, with the United States acting as an eventual mediator.

A Quarter Century of Occupation (Al Quds, West Bank)

by Jamal Al Afghani, 1992

via Palestine Poster Project

In September 1993, the Oslo Accords agreement was reached. Overall, Israel recognized the PLO as the representative of the Palestinians (previously they had designated them as a terrorist organization). Meanwhile, the PLO recognized Israel’s right to exist in peace – like it had already established by recognizing UN Res. 242 – and they also renounced Palestinian “terrorism.” The agreement opened with the statement:

“The Government of the State of Israel and the PLO team (in the Jordanian-Palestinian delegation to the Middle East Peace Conference) (the ‘Palestinian Delegation’), representing the Palestinian people, agree that it is time to put an end to decades of confrontation and conflict, recognize their mutual legitimate and political rights, and strive to live in peaceful coexistence and mutual dignity and security and achieve a just, lasting and comprehensive peace settlement and historic reconciliation through the agreed political process.

The aim of the Israeli-Palestinian negotiations within the current Middle East peace process is, among other things, to establish a Palestinian Interim Self-Government Authority, the elected Council (the ‘Council’), for the Palestinian people in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, for a transitional period not exceeding five years, leading to a permanent settlement.”

Palestinian President Yasser Arafat & then Israeli Foreign Minister Shimon Peres after signing Oslo I in 1993

Photo via Reuters

A coalition of ten Palestinian groups – including Hamas, Islamic Jihad, PFLP, and DFLP – issued a statement after that the agreement “meant perpetuating the Israeli occupation, transforming the Palestinians into its instruments, and establishing a Palestinian police force to protect Israeli security and repress the Palestinian people.”

They weren’t alone. Well-known Palestinian academic and philosopher Edward Said wrote a detailed reflection, The Morning After, where he called Oslo “an instrument of Palestinian surrender” and essentially described it as a slap in the face.

Amir-Hussein Radjy later wrote an article for the publication Foreign Policy, Edward Said Saw the Future of Israel and Palestine, where he spoke about Said’s research, work, and legacy. When describing his reaction to the agreement, Radjy writes:

“Said described the protests, strikes, and boycotts of the First Intifada in the late 1980s as ‘surely the most impressive and disciplined anti-colonial insurrection in this century.’ Instead of building on it, he felt Arafat signed away any gains in the nationalist cause for the U.S. government’s flimsy promises of being an honest broker. It was, he repeated over the next few years, the only time an occupied people had agreed to negotiate with their occupiers before a withdrawal had happened or been agreed on.”

Declaring “Our people reject the Oslo Accords” and celebrating the sixth anniversary of the Intifada

Poster by Mohammed Safi, 1993

via Palestine Poster Project

Physical Spaces for Art

To look at the initial impact of the Oslo Accords on visual art, the conversation starts just before it was actually signed. In Palestinian Art, Kamal Boullata writes:

“The 1990s ushered in a new era in the visual arts. With peace talks that seemed to hold out new promise for the establishment of an independent Palestinian state, the cultural scene was infused with a new energy. For the first time since 1967, new institutions devoted to the promotion of the visual arts provided proper exhibition space.”

Al-Wasiti initial logo, 1990s

via Palestinian Art Court – al Hoash

Multiple spaces opened in East Jerusalem, continuing its history as an art hub.

One of these was the Al-Wasiti Art Centre in East Jerusalem, founded by Sliman Mansour and other Rabita artists in 1992. It hosted solo and group exhibitions of local artists and offered courses to young kids. It also started a photography archive to document locally-produced art.

A page from materials around the Al-Wasiti opening

via Palestinian Art Court – al Hoash

The other was Gallery Anadiel, founded the same year by artist and curator Jack Persekian, along with his brother-in-law, who had been born in Al Quds / Jerusalem. While they also exhibited local artists, they also invited diaspora Palestinian artists to visit – several who had never been to their homeland before, such as multimedia and installation artist Mona Hatoum.

After the signing of the Oslo Accords and influx of international donations for cultural projects, many NGOs for visual arts were founded to solicit grants for Palestinian artists from an increase of international and diaspora contributions. This included NGOs organized by artists themselves.

The majority of cultural spaces instead shifted towards Ramallah – where the newly-established Palestinian Authority had their West Bank headquarters.

Artist Taysir Sharaf’s 1996 exhibit, the title of which translates to "Jerusalem and the Artist... Where to?"

Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center

via Palestine Museum Digital Archive

In Ramallah, one of the main openings at this time was the Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center in 1996 – initially as a branch of the Palestinian Ministry of Culture. The first director was Adila Laïdi-Hanieh, who oversaw its transition to become an NGO.

Laïdi-Hanieh also developed programs across the visual arts field to host exhbitions for artists across the West Bank and Gaza, including a focus on young artists in particular.

Along with exhibitions, the venue also hosted other events such as lectures, screenings, concerts, and more. It became a key cultural hub in the West Bank. There were also literature programs and the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish even had an office there.

An important institution that opened in 1998 was the A. M. Qattan Foundation that operated through a family endowment and helped to fund other cultural institutions and programs throughout Palestine, in addition to creating its own programs.

A page from a brochure for the 1996 exhibit for artist Taysir Sharaf

Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center

via Palestine Museum Digital Archive

Universities & Art Programs

There had been no art schools available to study at prior, so Palestinians who were interested in studying the craft had to go to neighboring countries – such as Egypt, Iraq, and Syria – if they were even permitted or able to travel.

Not until the early 1990s were art programs and student exhibition venues able to pop up more at schools like Al Najeh University and Al Quds University, though it would be another decade before the first art academy would be established. This would be the start of an increasing amount of such university arrangements over time.

These schools also assisted in the larger art field development. Tina Sherwell wrote in an article for IEMed:

“(Universities) took on different roles, hosting solo shows for artists, documenting Palestinian art, creating websites, producing publications, promoting contemporary and avant-garde practices, creating bridges between Palestinian artists inside the green line and in diaspora, creating links between international artists and Palestine, organizing international exhibitions of Palestinian art, hosting international artists, creating residency programs, and facilitating the work of international curators.

In time, these institutions have become cultural mediators and set the agenda for cultural activities through their strategies and programs.”

Part of "The Eyes of Tel al-Zaatar" exhibit at Khalil Sakakini Cultural Centre in 1999

by Abed Abdi

via Palestinian Museum Digital Archive

Breaking Recent Traditions

After such a long stretch of art that often tied to political contexts and nationalist symbols, the 1990s saw a shift to exploring more personal themes. They still were rooted in the history and informed by the political context, “but did not revert to the use of the established visual iconography and popular symbolism of identity representations of previous decades” as Tina Sherwell wrote for IEMed.

Sherwell also notes that the mediums changed:

“Painting and sculpture had been the dominant modes of expression but this began to shift with younger generation artists, who began to use photography, video and installation, and experiment with performance.

With a lessening of a direct political agenda in art practice over the mid-to-late 1990s, as well as of the need to create national representations, younger artists in particular began to engage with more complex investigations of questions of identity and location.”

Cinema Continuing To Grow

One medium that was seeing increasing popularity was filmmaking. After the PLO had been at the forefront of Palestinian cinema from the end of the 1960s through the start of the 1980s, with films often tied to national Palestinian organizations, this changed after the Lebanon invasion and withdrawal of the PLO from Beirut. Instead, it became more independent with individuals making their own work, while still often speaking to the Palestinian struggle.

One notable example was Wedding in Galilee (1987) – the first-ever fictional, feature-length movie that was made in Palestine by a Palestinian director. Directed by Michel Khleifi, the film won the International Critics Prize, or FIPRESCI, at the Cannes Film Festival in 1987.

حتى إشعار آخر, or Curfew (1994)

Directed by Rashid Masharawi

From the new filmmakers who started to emerge during the ‘90s, one of them was Rashid Masharawi, who released حتى إشعار آخر (Curfew) in 1994. It was about Palestinians living in al Shati refugee camp in Gaza, the same camp he had been born and raised in.

Masharawi also established the Cinema Production and Distribution Center (CPC) in Ramallah in 1996. The goal was to organize workshops and present opportunities to learn, hands on, for young Palestinian filmmakers. The CPC also ran a Mobile Cinema, with screenings at refugee camps during an annual Kids Film Festival.

The first Palestinian movie to receive a national release in the United States came in 1996, with Elia Suleiman’s film (Chronicle of a Disappearance (سجل اختفاء).

The movie, starring Suleiman himself, also won the Best First Film Prize at the Venice Film Festival. It features vignettes that are meant to convey the reality of daily Palestinian life under Israeli occupation.

Suleiman himself had lived in New York City for a period but had moved back to Palestine in 1994 and taught at Birzeit University in the West Bank, here he worked on developing a Film and Media Department at the school.

Image from Chronicle of a Disappearance (1996)

Directed by Elia Suleiman

The Agreement Unfolds

The first Oslo Accord, known as Oslo I, was signed in September 1993. As noted in an article from The Middle East Institute for Understanding:

“The Oslo Accords established the Palestinian Authority (PA) to govern Palestinians in pockets of the occupied West Bank and Gaza under the control of Israel’s occupying army.

The PA was supposed to be an ‘Interim Self-Government' and only last ‘for a transitional period not exceeding five years.’

The final status agreement was supposed to be based on United Nations Security Council Resolution 242, which called for Israel to withdraw from the territories it occupied during the June 1967 war, including the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and Gaza.

As a result, most Palestinians believed that the Oslo Accords would create an independent Palestinian state in the occupied territories alongside Israel, as part of the so-called ‘two-state solution’ in Palestine/Israel advocated by the international community.”

A second accord, Oslo II, was signed in September 1995. It included more details on steps for the process. Notably it divided the West Bank into three areas: Area A (complete PA authority), Area B (shared security agreement), and Area C (“Isreali” authority).

It had been agreed that a general election would happen for the West Bank and Gaza. In January 1996, the PA held elections and Arafat’s Fatah party won with 88% of the vote.

"Palestine: Together in building our land"

Artist unknown

Issued by the Central Elections Committee in November/December 1995

via Palestinian Museum Digital Archive

There had been a deadline of May 1999 for a permanent resolution of the Oslo matters to be reached.

However, by the end of the decade, no final peace treaty or semblance of peace was achieved. There was a large increase in settlements, with more than double in the West Bank.

In addition, other original aspects of the deal were not kept.

One notable element that also had consequences was the way the Palestinian Authority (PA) was run. As mentioned in the Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question:

“The PA also became increasingly authoritarian. It cracked down on opponents, especially from Hamas, and often ignored court rulings or resorted to special military courts.

In addition, with Arafat and Fatah focused on running the PA and continuing the process of negotiations with Israel, and with the Damascus-based groups seemingly permanently alienated, the PLO as representing also the diaspora Palestinians virtually ceased functioning. Many Palestinians, even refugees in Syria and Lebanon, who had initially supported the Oslo accords and welcomed the establishment of the PA as a step toward Palestinian independence saw little hope in the whole Oslo process.”

When the US invited both parties for a Camp David Summit in July 2000, Israel said it would not make any concessions about the return of refugees, nor any changes to the status of Jerusalem. The Oslo “peace process” was resulting in a failure for Palestinians.

2000 Camp David Summit

A later painting by Romanian artist Gheorghe Virtosu in 2017

via Virtosu Gallery

Zoom Out:

20th Century Overall

A pause in the chronology to look at some aspects of how the arc of the art movement developed overall from the Nakba to the end of the 1900s.

Disjointed Growth

Palestinian artist and historical expert Kamal Boullata looks back on the 1948 Nakba and the destruction of society in his book Palestinian Art, saying it made it “almost impossible to trace the budding art movement that was taking root in the country before the national catastrophe that precipitated the deracination and dispersal of the Palestinian people and the looting of art works from abandoned urban homes.”

Some artists were displaced in neighboring Arab countries, initially cut off from the artists back home or others in the diaspora. Some artists were refugees in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, living in camps. Some artists lived inside the ‘48 territories, living as degraded citizens of their own homeland and also cut off from the rest until 1967.

Ismail Shammout at his first exhibition in Gaza, 1953

via Tamam Al-Akhal and the Shammout family archive

Tamam Al-Akhal painting in her studio, 1970s

via Tamam Al-Akhal and the Shammout family archive

While there’s a clear difference in how art developed after the Nakba, it’s worth noting key players who helped bridge the gap. This included Daoud Zalatimo, the early 20th century artist who taught Ismail Shammout, who would then go on to influence many artists of his time. In The Origins of Palestinian Art, authors Bashir Makhoul and Gordon Hon write:

“Zalatimo is regarded as a key transitional figure between the religious and secular paintings of Saig and the development of painting and the production of Palestinian visual culture after 1948…

He did this by using historical events and figures in Arab history, such as Saladin, which could be read as allegories for the current situation or act as inspirational figures for resistance and revolt…

This kind of imagery was easily transferred to the liberation art of the second half of the twentieth century, and the technique of allegorizing Palestinian resistance in historical painting was particularly useful for Palestinians living inside Israel and the occupied territories who, particularly during periods such as the first Intifada, were working under draconian Israeli censorship.”

The standout artists of the 1948-2000 period really focused on nationalist works that emphasized the resilience, determination, humanity, difficulty, and all-encompassing Palestinian life.

The Last Summer in Palestine

Painting by Sliman Mansour, 1994

via artist archive

Further Out, More Abstract

The emphasis on explicit national Palestinian ideas and symbols for the art of this time, however, was less present in a certain group of artists.

Kamal Boullata, who split time between the US and Europe, writes in Palestinian Art: “It is interesting to note that, soon after the 1948 debacle, the closer the artists lived to the home culture and country of birth, the more figurative their art was, and the further away they settled the more their art evolved into abstraction.”

While it was most common for those displaced to find exile in places like Lebanon or Jordan, some also ended up in further destinations.

Boullata himself fit his own description perfectly. He split time between the US and Europe, where his work explored different abstract ideas.

Three Quartets

Kamal Boullata, 1994

via Jordan National Gallery of Fine Arts

Three Quartets

Kamal Boullata, 1994

via Jordan National Gallery of Fine Arts

Three Quartets

Kamal Boullata, 1994

via Jordan National Gallery of Fine Arts

Three Quartets

Kamal Boullata, 1994

via Jordan National Gallery of Fine Arts

You can also see the correlation in the art of Vladimir Tamari, who ended up in Tokyo, Japan.

Part of "The Eyes of Tel al-Zaatar" exhibit at Khalil Sakakini Cultural Centre in 1999

by Vladimir Tamari

via Palestinian Museum Digital Archive

Untitled

Watercolor by Vladimir Tamari, 1993

via artist archive

Untitled

Watercolor by Vladimir Tamari, 1987

via artist archive

Jerusalem from the Far East

Watercolor by Vladimir Tamari, 1982

via artist archive

Or with Sari Khoury, who came to the US (based in Michigan).

Among the Ruins

Painting by Sari Khoury, 1990

via MutualArt

Untitled/undated painting by Sari Khoury

via artist archive

Untitled/undated painting by Sari Khoury

via artist archive

And to round out this group of painters, there is Samia Halaby, based in the US (first around the Midwest and then New York City since the mid-70s).

Fire, 1975

Painting by Samia Halaby

via artist archive

Autumn Leaf Study, 1975

Painting by Samia Halaby

via artist archive

Position Interplay, Light

Painting by Samia Halaby, 1980

via artist archive

Untitled, 1982

Painting by Samia Halaby

via artist archive

Fruits and Gourds, 1994

by Samia Halaby

via artist archive

Quiet Fire in Blue Sky, 1999

Painting by Samia Halaby

via artist archive

Writing The Record

In addition to her own work, Samia Halaby became a key documentarian of Palestinian art history. In the 1990s, she started to take trips to visit Palestine more and began to meet with a lot of artists. Halaby would also put the interviews on her original website, as she always tried to embrace new technologies.

At the time, Sliman Mansour was the head of al-Wasiti Art Center in Al Quds. He saw Halaby had taken this interest in other Palestinian artists and commissioned her to write a 40-page paper. Halaby shares about this process:

“Research began in earnest after talking to Sliman Mansour, who suggested that I rent a car and drive inside the green line to Palestine ‘48, the Israeli entity, in 1999.

I was scared but Sliman encouraged me. I called artists whose numbers he had given me and met and interviewed them. I made great friendships. When inside the green line, both sides (those exiled and those living inside) immediately feel that we have to pack a lifetime of acquaintanceship into a few hours. A great empathy results.

In the end, I interviewed 46 artists before starting the book. I also collected and read any and all printed material that I could find… I wanted to pursue an art historical tradition by not only analyzing what I had discovered in my field research but by seeing how it fits into an international historical context.”

Palestinian artist and educator Fathi Ghaben painting while his daughter plays outside

Photo by Mike Abrahams

Halaby’s important research and conversations evolved from a paper into a book, Liberation Art of Palestine: Palestinian Painting and Sculpture in the Second Half of the 20th Century.

It was the first English-language book of its kind. In looking back at Palestinian visual art over the 20th century, she writes how it blossomed when there was great hope for achieving freedom.

Identity by Fathi Ghaben, 1980

Halaby puts this work into a historical and international context:

“The spirit of Palestinian artists relies on historical tradition and on the resourcefulness and revolutionary potential of refugees, who were once tillers of the soil but are now the lowest paid workers, bravely confronting severe oppression…

The Paris Commune powered Impressionism. The struggle for the eight-hour day gave the Chicago School of Architecture its impetus. The Soviet Revolution brought the incredible birth of Abstraction to mankind. The Industrial Union movement in the US inspired Abstract Expressionism.

Likewise, the art of Palestine rests on the Palestinian struggle for liberation. Without that base, Palestinian artists would be an atomized collection of imitators of fashionable international styles, and many are.

The liberation artists of Palestine are aware that they are fortunate to have a cause, and in fulfilling their duty to serve it, their art gains historical significance as a school with particular characteristics at the close of the 20th century - a century of dual power, in art as in politics.”

The end of the 20th century was a time of limbo, in a way. Any potential hope some had of the Oslo Accords soon soured with the lack of action to improve life for Palestinians. As a result, art would soon naturally undergo a shift with the times.