Part 3 -

Palestinian Art History

Artists Get Organized

1970 - 1980

A prolific decade of art by both Palestinians and those in solidarity of the cause, with many important efforts that tried to bring artists together and people together.

Rabita / The League of Palestinian Artists

After the growing unity among artists during the end of the 1960s, there was an effort to more formally organize together. An artist association was established in 1973 by a group of artists that included Sliman Mansour, Nabil Anani, Isam Badr, and more.

Samia Halaby refers to this group as the Rabita (رابطة), while Kamal Boullata and others call it The League of Palestinian Artists. (While both names apply, Rabita will be the name used below.)

Jamal al-Mahamel (Camel of Hardship)

Painting by Sliman Mansour, 1973

Printed as a poster in 1975 and 1980

via artist archive

Palestinian painter Sliman Mansour was born in 1947 and spent his childhood in Bethlehem and Al Quds, then under Jordanian sovereignty after the 1948 Nakba.

Mansour excelled in art from a young age and was planning to go abroad for art school. After the 1967 Naksa where Israeli forces seized the West Bank, however, he was exposed to a greater understanding about Palestinian history and stories. This greatly influenced the work Mansour would soon make, incorporating symbols of Palestinian identity.

For the Rabita overall, they felt that accessibility was important. So they took their art and utilized the easy production of posters to be able to efficiently spread the work, just as the PLO and others had adopted. Mansour says the united artists shared common themes often integrated across the group – including prisoners, martyrs, the Earth, Al Quds, land confiscation, eviction, sumud, and roots.

In her book Liberation Art of Palestine, Samia Halaby says that the Rabita were also intentional about how they captured these ideas, making sure to emphasize Palestinian history and culture.

Palestinian artists painting a landscape of Ras Karkar (West Bank)

Left to right: Isam Badr, Kareem Dabbah, Nabil Anani, and Sliman Mansour

via Palestinian Museum Digital Archive

Halhul village of Palestine

Postcard of a 1977 painting by Nabil Annani

via Palestinian Museum Digital Archive

This included when taking trips to villages to paint – where the Palestinian artists would ignore any settlements or new Zionist infrastructure and instead focus on the Palestinian land and buildings that had been in existence. Halaby writes:

“It is a declaration of artistic war against the Orientalist Painters who came to Palestine as part of the colonization process to paint what is to them the quaint villages of 'The Holy Land.’

Members of the Rabita carried their supplies and traveled to villages, working directly from nature. The return to the village was a return to undamaged Palestine.”

Mayor of Nablus, Bassam al-Shaká, opening a 1975 exhibit for the Rabita at Nablus Public Library

Photographer unknown

via Palestinian Museum Digital Archive

Their first group show in 1975 focused on many of these subjects. It opened in Al Quds and soon traveled to Ramallah, Nablus, Jericho, and to Gaza – before later heading to Amman and London as well. Mansour and artist Vera Tamari said the exhibit was a landmark in the formation of a popular Palestinian art movement. “To most people, this art was the ultimate expression of patriotic commitment,” they noted. “The aesthetic value of the works was secondary."

These exhibitions would take place in schools, town halls, public libraries, and any other places that could host – given the lack of actual art spaces. They became a community event and continued to gain traction in bringing locals out to shows.

Additional exhibitions hosted in the 70s also had specific themes such as the Palestinian Village, the Day of the Prisoner, the Year of the Child, and the Day of the Land.

The Rabita’s exhibitions were popular with the Palestinian community. That also meant that Israeli powers soon took notice and decided it was an issue.

In Palestinian Art, Kamal Boullata writes:

“Initially, the military authorities monitoring Palestinian cultural events did not assign any importance to what they regarded as marginal activities.

The Palestinian public, on the other hand, suffering from both repression and defeat, regarded each artistic work that came to light under the grim Israeli military presence as a source of national pride and self-reassurance.

Gradually, exhibitions became rallying events that the occupation authorities came to see as emblematic of a collective national identity and crucibles of defiant resistance to occupation. Strict censorship of all art exhibitions followed, and even those that received permits from the military authorities were prone to have their openings raided by soldiers, the exhibition space closed down, and the crowd dispersed.”

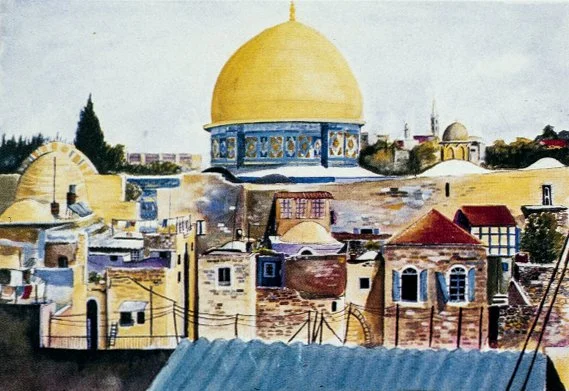

Dome of the Rock at Al-Aqsa Mosque in Al Quds

Postcard of a painting by Taysir Sharaf

via Palestinian Museum Digital Archive

Samia Halaby says that an attempt was made to burn the art of the Rabita’s third group show in 1976, but it had luckily been stored at a location outside of the exhibition hall. However, the Ramallah opening was still disrupted by the military. The fourth group show, in 1979, was dedicated to the Year of the Child. Work was made looking at the safety, health, and education of children under occupation. When the show traveled to Gaza, artworks were stored at the Red Crescent offices. However, all paintings were then destroyed by arsonists.

In 1979, Gallery79 was established in Ramallah by another Rabita artist, Isam Badr. In another group exhibition there in September 1980, the Israeli military governor and his soldiers confiscated a handful of paintings and posters. That same month, Sliman Mansour’s first ever solo show only lasted four hours before being shut down. Shortly after, the gallery was closed.

Harvest

Painting by Sliman Mansour, 1977

via artist archive

Early in the Morning

Painting by Sliman Mansour, 1978

via artist archive

During this time, the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) also created another group – the Union of Artists for Palestinians – to organize artists in the diaspora, as the Rabita only included those in occupied territories of Palestine.

2nd General Exhibition for the Lebanon Branch of the Union of Palestinian Artists, at Beirut Arab University

Poster by Ismail Shammout, 1979

via Palestine Poster Project

1978’s International Art Exhibition For Palestine

Beirut continued to be an artistic center for displaced Palestinians in the 1970s – as it had been since the ‘50s – and was argued by some as the most crucial place for Palestinian art in general. Displaced creatives there made work around their experiences in exile and the nostalgia they had for their homeland.

It was fitting that Beirut was the home for the International Art Exhibition For Palestine in 1978. The show was organized by Mona Saudi, a Jordanian sculptor who ran the Plastic Arts section of the PLO.

Brochure for the 1978 International Art Exhibition for Palestine

The exhibit opened at Beirut Arab University in Lebanon with art that included around 200 artists from 27 different countries – Algeria, Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Chile, Cuba, Denmark, Dominican Republic, Egypt, France, Germany, Hungary, India, Iraq, Italy, Japan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Palestine, Peru, Poland, Romania, Spain, Syria, US, Venezuela, and Yemen.

Mona Saudi’s curator note in the exhibition catalog reads:

“After 1948, the Palestinian art-expression, whether through word of colors, presumed a tragic form, expressing the miserable situation of usurpation under Israeli occupation or under the tutelage of oppressing Arab regimes. With the birth of the revolution, there started the process of creating the new man: self-confident, aware of his capability to restore his right and raise his voice.

The armed struggle promoted a creative atmosphere among the Palestinian people and in the Arab world in particular and in outside world in general. This creativity growed and cristalized itself along with the growth of the revolution.

Algerian artist Baya

International Art Exhibition For Palestine of 1978

French artist Claude Lazar

International Art Exhibition For Palestine of 1978

(Mona Saudi’s note continues:)

As a result, the Arab artists adopted the Palestinian cause as an art-content and expressed it by creating advanced, modern art styles that emphasizes the unty of the struggle and the problems of Arab people, as well as its deep-rooted links to the Palestinian cause. Other artists all around the world adopted the subject of the Palestinian struggle in their art-expression, showing the human essence of our battle.

All the works in this exhibition are gifts from the artists to the Palestine Liberation Organization. At the end of the exhibition, all these works are going to constitute the nucleus of the 'Museum of Solidarity with Palestine.' During the exhibition, we will try to push forward idea of establishing this museum and to put up an international committee, including artists, as well as other friends, so as to put the idea into action. We hope this museum to be a permanent center for developing and strengthening the militant activities and relations between our people and the peoples of the world as well as our artists and the world artists for the sake of the cause of freedom and peace.”

Syrian artist Elias Zayat

International Art Exhibition For Palestine of 1978

Japanese artist Tetsuo Iguchi

International Art Exhibition For Palestine of 1978

In Samia Halaby’s book Liberation Art of Palestine, she writes:

“The catalog contains many messages of solidarity from artists, including one from the internationally known Latino painter Roberto Matta, who contributed a pastel titled Palestinian Martyrs.

From Spain, internationally established and deeply respected artists such as Edouardo Chilida, Joan Miró, and Antonio Tàpies, contributed works for the exhibition.”

Spanish painter Joan Miró

International Art Exhibition For Palestine of 1978

Morrocan artist Mohammed Kassimi

International Art Exhibition For Palestine of 1978

There were also Palestinian artists who participated – including Tamam Al-Akhal, Ismail Shammout, Sliman Mansour, Kamal Boullata, Ibrahim Ghanniam, Vladimir Tamari, and more.

Palestinian artist Ibrahim Hazina

International Art Exhibition For Palestine of 1978

The show would also go on to travel internationally – such as in Japan, Norway, and Iran. It was also exhibited locally at the Shatila refugee camp in Lebanon, home to many displaced Palestinians who loved the art. The catalog was even delivered to fedayeen fighters in the field.

It was the most ambitious and expansive art initiative to date for the PLO at that point. The exhibit was a clear success in showcasing global solidarity and collecting pieces for the intended future museum.

Italian artist Paolo Ganna

International Art Exhibition For Palestine of 1978

Chilean artist Gracia Barrios

International Art Exhibition For Palestine of 1978

Poster Art

Posters had started to become a popular method in the 1960s to share messages and art due to their affordability, ease of production, and ability for mass-distribution.

This continued in full force into the 1970s behind the PLO, PFLP, DFLP, and Fatah – as well as other groups or individuals looking to capture the struggle through these means. The General Union of Palestinian Students (GUPS), for example, spread on campuses across Europe.

To make posters, these different groups sometimes worked directly with Palestinian artists, though not exclusively. When they did, the the artists had a lot of freedom to experiment in presenting different visual approaches.

Hero Ghassan Kanafani (1st anniversary of martyrdom)

Artist unknown, 1973

via Palestine Poster Project

7th Anniversary, DFLP

DFLP poster by artist unknown, 1976

via Palestine Poster Project

Land Day In Palestine - March 30, 1976

PLO poster by artist unknown, 1976

via Palestine Poster Project

We Have Survived Hunger - Tel al-Zaatar massacre in 1976

PFLP poster by artist unknown, 1976

via Palestine Poster Project

11 Years of Popular Armed Struggle

PFLP Poster by Artist unknown, 1978

via Palestine Poster Project

In the Zionist Prisons

Poster by Yusuf Hammou, 1975

via Palestine Poster Project

2nd Anniversary of the September massacre

Artist unknown, 1972

via Palestine Poster Project

Negotiating Game

Artist unknown, 1975

via Palestine Poster Project

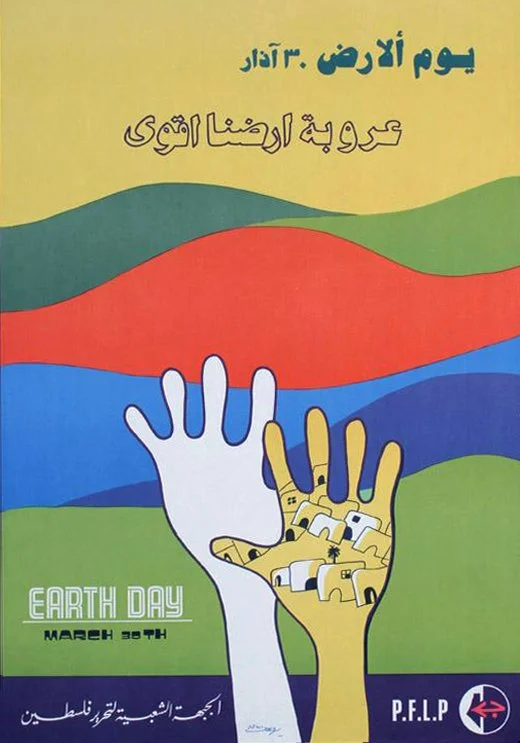

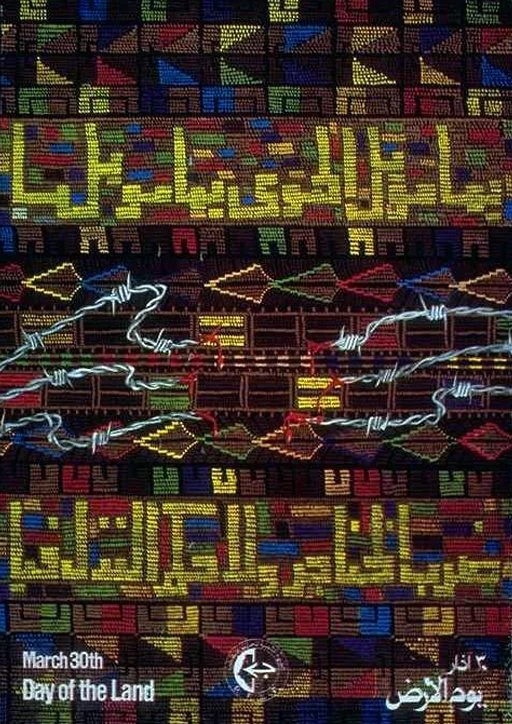

Land Day

Artist unknown, 1979

via Palestine Poster Project

These posters told stories of martyrs, feyadeen, refugees, workers, prisoners, and more. They often incorporated national symbols and phrases as well.

The designs also captured both modern and past historic moments, including tragedies that were seldom covered in international media, like the Tel al-Zaatar massacre in 1976.

Certain annual commemorations, such as for Land Day, with the first in 1976, become recurring themes in posters.

These were intended for an international audience, including the larger Arab region, but in particular they applied to a Western audience that so often dehumanized Palestinians.

While the resistance fighters took up the most dangerous and important fight of armed struggle, the cultural approach worked to support and spread messages of the people.

Earth Day

PFLP Poster by Yusuf Al Nasser, 1976

via Palestine Poster Project

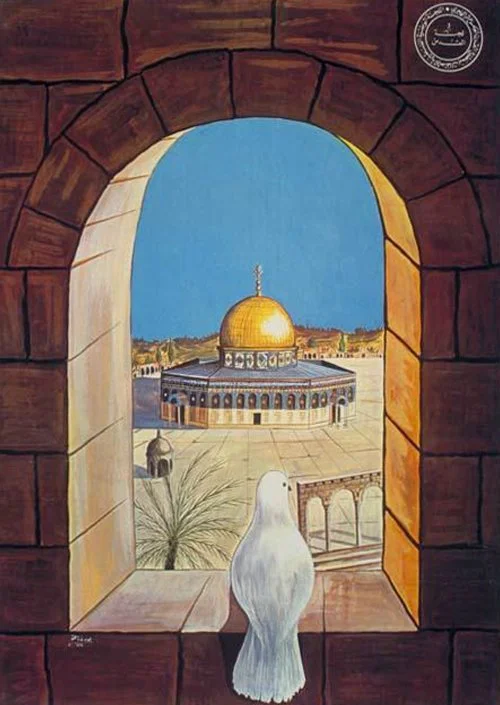

A Window on Jerusalem

Poster by Yusuf Hammou, 1979

via Palestine Poster Project

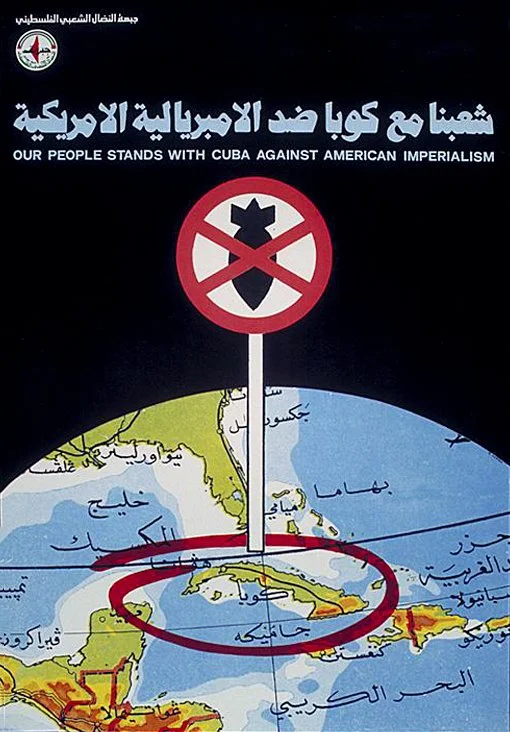

Joint Struggle, from Cuba

Artist unknown, 1978

via Palestine Poster Project

Our People Are With Cuba (Palestinians in solidarity)

Poster by Mahmud Dawirji, 1980

via Palestine Poster Project

Land Day

PFLP poster by artist Unknown, 1980

via Palestine Poster Project

Strive With Sincerity

Artist unknown, 1980

via Palestine Poster Project

PLO representatives also launched poster contests in places such as Poland and Japan for people to submit their own depictions of the Palestinian struggle.

Sometimes, non-Palestinian artists also were brought in to work on poster designs. For example, in 1979 the PFLP faction of the PLO hired Switzerland-born artist Marc Rudin, who had been very politically active since the 1960s and making posters in support for the Palestinian since the mid-1970s. Also working under the name of “Jihad Mansour” in his designs, Rudin would go on to work with the PFLP over the next decade.

Other artists around the world also created posters to show their own country’s support, or just their own personal perspective, in unity for the Palestinian cause. But no matter who was designing it, the form itself took on its own life.

Palestine Needs Arab Solidarity

Poster by Hosni Radwan, 1980

via Palestine Poster Project

The Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question writes:

“The study of posters differs from other sub-fields in art history because posters are at the intersection of an artistic practice and a skill in the advertising industries. A poster is a medium reproduced in serial editions using off-set, lithography, and serigraphy. As such, its monetized value can never reach that of an art work.

However, a poster can be as much a masterful accomplishment as any work of art, and because of its serial nature, its modes of dissemination make it sometimes more impactful and more subversive.

In the realms of militant and politically radicalized artistic practice, posters hold a special place because artists regard them as an instance of creative expression geared toward popular mobilization. In the conventions of poster design, the visual composition and graphic elements of a poster should speak to a decipherable collective imaginary, use widely known symbols, stylization and strong contrasts.”

Palestinian Cinema Institution logo

via Khadijeh Habashneh

A Decade of Resistance Cinema

The Palestine Film Unit of the PLO relocated to Beirut in the early 1970s and was renamed the Palestinian Cinema Institute. They continued to make work documenting the resistance fighters and ongoing struggle for liberation. They wanted to attract global attention for the Palestinian revolution and mobilize international solidarity.

The Institute was also in contact with film-makers from other countries who “viewed the camera as a revolutionary tool in the people’s struggle,” sometimes leading to collaborations.

Mustafa Abu Ali headed the department from 1973 to 1975 and would go on to direct over 30 films himself. This included Scenes of the Occupation from Gaza (1973) – a half-century before the Gaza genocide would take place.

Another notable film Abu Ali worked on in this period was Palestine in the Eye (1976) about his fellow Film Unit co-founder, Hani Jawharieh, who had been martyred while filming for their team the same year the film was made.

Hani Jawharieh tribute in Falastin Al Thawra Magazine

April 1976

via Vladimir Tamari’s archive

Palestine in the Eye documents Jawharieh’s life and features relatives, friends, and others discussing his determination. A quote from that film also expresses the larger goals of all of the Palestine Cinema Institute during this period:

“Resistance cinema is a cinema that expresses the aspiration of a people. It records their struggle for freedom. It communicates their experience to the rest of the world.”

The Film Unit’s work traveled and was shown in countries and festivals around the world. A dedicated Palestine Film Festival also ran in Baghdad during 1973, 1976, and 1980.

PCI members Samir Nimir and Khadijeh Habashneh, 1979

via Khadijeh Habashneh

Khadijeh Habashneh had married Mustafa Abu Ali in 1968 and had volunteered with the group since its early origins in the late ‘60s.

In 1976, Habashneh organized an official archive for the group’s works, which she was in charge of. That year, she also established a cinematheque that screened films from other liberation groups all over the world (Cuba, Vietnam, China, and the Soviet Union).

Habashneh became a director later in the ‘70s, too, with Children Nevertheless (1979) about orphans from the Tal al-Zaatar massacre, as well as an unfinished film about women’s role in the resistance.

Other Palestinian factions like the PFLP and DFLP had started to use film as a tool during the 1970s as well. The medium was seen as a valuable for capturing and communicating ideas, and preserving history.

Lebanon Invasion &

Banning of Colors

1980 - 1987

Artists tackle restrictions while Palestinians in the diaspora face attacks in Lebanon.

Still from Return to Haifa movie (1982)

Cinema Steps & Lebanon Invasion

Outside of a documentary approach, the film world also started to expand with the first fictional Palestinian movie, Return To Haifa (1982). It was based on a novel of a similar title, Returning to Haifa, by Palestinian writer Ghassan Kanafani.

The movie was shot in Lebanon. The PFLP raised the money and it was directed by an Iraqi filmmaker, Kassem Hawal, who had been politically exiled and become a longtime contributor of the PLO Film Unit / Cinema Institute.

Shortly after the film was completed in 1982, Israel invaded southern Lebanon that same year.

Palestinian refugee children walk to school amidst the rubble in Shatila camp, Lebanon

1982, Photo by George Nehme

via UNRWA archive

As summarized in The Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question:

“The 1982 Lebanon War was a three-month conflict precipitated by the Israeli invasion of Lebanon, designed to militarily and politically debilitate the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and turn the Lebanese Civil War in favor of Israel's right-wing allies...

The war was immensely destructive in terms of both lives and property, worsened the Lebanon's already civil war-torn political fabric, and led to an Israeli occupation of parts of Southern Lebanon that lasted until 2000.

The war also proved a massive setback for the PLO and its leader, Yasir Arafat, who was forced to leave Lebanon and establish new headquarters in Tunis.”

The worst of the attacks was the Sabra and Shatila massacre in Beirut, where Israeli forces attacked the joint Palestinian refugee camps – leaving around 3,000 martyrs over a three-day period.

Sabra and Shatila massacre of Palestinian refugee camps in Beirut, Southern Lebanon

1982, Photographer unknown

via UNRWA archive

Eyes Are Open - Sabra Shatlia massacre

PFLP poser by Abu Manu, 1982

via Palestine Poster Project

A Blossom in Shatlia

PLO poser by Abu Manu, Abdel Aziz Ibrahim

via Palestine Poster Project

During the overall invasion on Beirut, the PLO buildings there were intentionally attacked.

As a result, most of their cinema archive was never to be seen again, leaving behind few traces of all the great work they’d made over that time. It is unclear how much of the vast archive – reportedly over 100 films – was destroyed, stolen, buried, burned, or lost. But very few works were left, or have since been recovered, in the hands of Palestinians.

The Palestine Cinema Institute, otherwise referred to as the PLO Film Unit, had made an impact with capturing and sharing moving images of their people’s struggle. Palestinian filmmaker Emily Jacir later wrote for The Electronic Intifada:

“Over a period of fourteen years the PLO Film Unit recorded Palestinian history and created films. They documented military actions, revolutionary events, the Palestinian resistance, everyday life in the refugee camps and they promoted the Palestinian national cause…

Unlike the national cinema that emerged out of Cuba after the Cuban Revolution, and out of Iran after the Islamic Revolution, the Palestinian national Cinema was created and documented life during the revolution.”

Animating the Present

Poster by Abdel Rahman Al Muzain, 1985

via Palestine Poster Project archives

International Art Collection Attacked

Also targeted by airstrikes during the 1982 Lebanon invasion was the recently-started Museum of Palestine in Beirut collection, which included all the artworks from the 1978 International Exhibition for Palestine.

Curator Mona Saudi and her sister did their best to rescue pieces that had not been initially damaged and continue to find safe homes for them. However, more would later be stolen and ultimately the majority of the art was destroyed or taken, in one way or another.

Italian artist Sami Burhan

from previous International Art Exhibition For Palestine in 1978

via Palestinian Museum Digital Archive

Outside of the exhibit or PLO aspects, the end of this period in Beirut had a broader effect. For over three decades, the Lebanese capital had served as a hub for both Palestinian refugees and the larger Arab world.

Kamal Boullata writes in his book, Palestinian Art:

“Beirut may be invisible in the works of Palestinian artists who lived there for almost three consecutive decades, yet nowhere outside the Lebanese capital could their art have evolved in the way it did there.

Seemingly oblivious to Lebanon's landscape, the focal subject of generations of Lebanese painters, Beirut's Palestinian artists were haunted by the experience of their displacement and the memory of a birthplace that was overnight rendered beyond reach.”

With the Israeli invasion, however, the PLO and most Palestinian artists in exile were forced to leave Beirut and things were no longer the same.

Censorship Rises Further in Palestine

In the early 80’s, Sliman Mansour and other Palestinian artists in the country were told by Israeli head officers that every piece of art would have to be given a stamp of approval. If it didn’t meet their standards, it would be confiscated.

The most egregious form of censorship came in 1980 when the basic colors of the Palestinian flag – red, white, green, and black – were put under a strict ban in artwork. This was after the flag itself had already been “banned” since 1967.

Painting by Isam Badr

Untitled and undated

When Israeli officers gave Mansour and other Rabita artists these guidelines, Isam Badr asked about painting a flower in those colors. Badr was told it would be taken. The officer then added “Even if you do a watermelon, it will be confiscated.”

The suppression, confiscation, and targeting of any form only made it stronger. The watermelon, for example, became a symbol of resistance at the time, and has remained one to this today. Other hidden symbols were also placed in the artworks to evade censorship and reach the people.

Badr himself had been targeted for his art and was ultimately arrested three times and had many works taken. Israeli soldiers also beat him in front of his students, in the streets, and in front of his house – all multiple times. Between this and the several periods of jail time, Badr ended up having a heart attack at thirty four years old, though he survived. Due to his health, he decided to withdraw from any activism.

Others decided to take the risk of continuing to fight through their art.

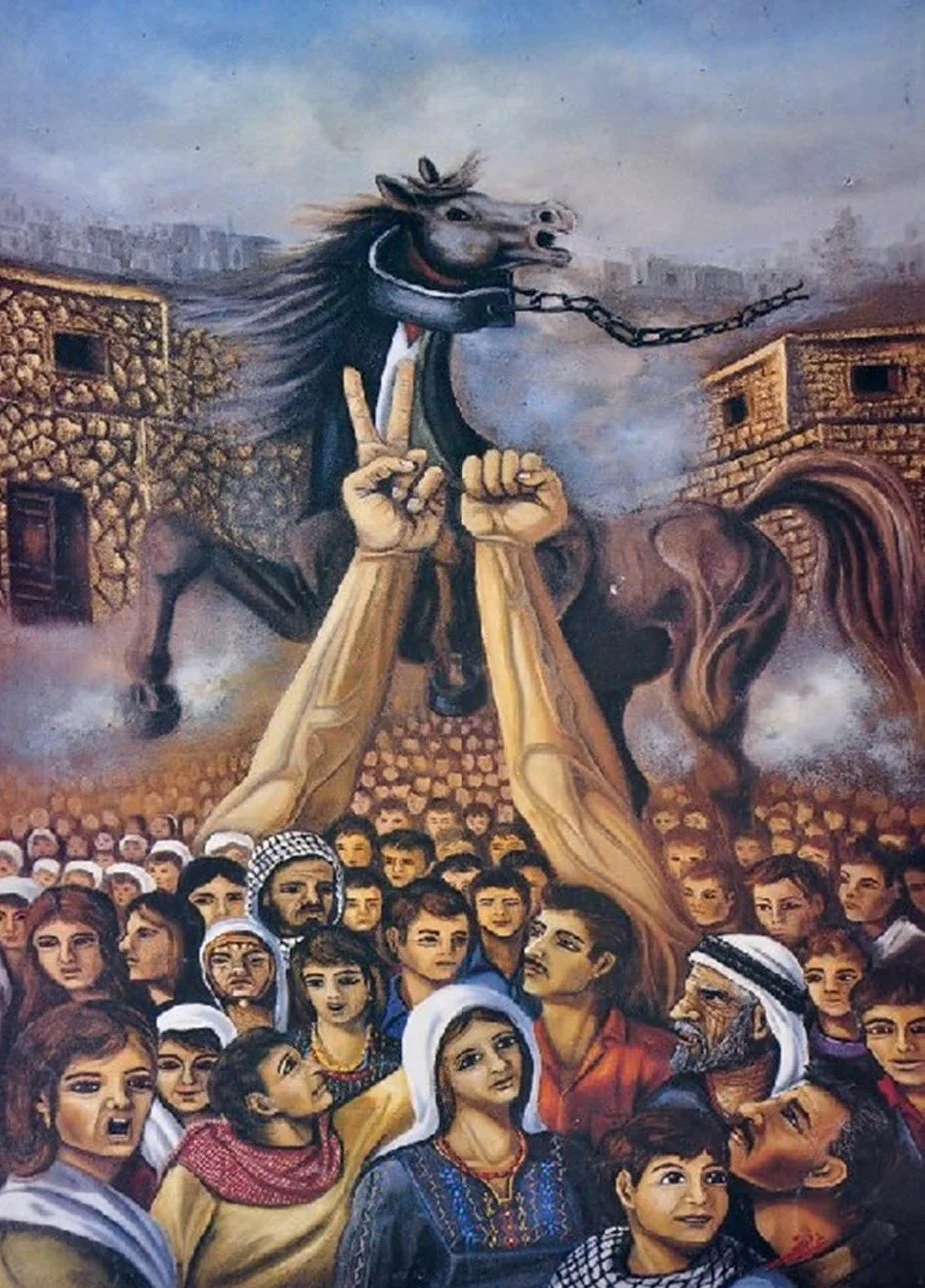

Painting by Fathi Ghaben

Untitled and undated

When Israeli soldiers martyred the nephew of Rabita artist Fathi Ghaben, he made the decision to paint the boy wrapped up in the Palestinian flag. The artwork went on display at Ghaben’s exhibit in 1984, where the show was abruptly closed. The painting of his nephew, along with six other works, were permanently confiscated by Israeli Occupation Forces.

The Israel military court found Ghaben guilty of breaking their color ban law. They also claimed his painting created incitement (while they were, of course, the ones responsible for the violence against his nephew in the first place).

Ghaben was imprisoned for several months as a result. Overall, he would eventually be jailed three times.

After getting released at one point, Ghaben is said to have painted the image of a mass demonstration and two arms rising into the air, along with a broken chain, and a horse with a subtle Palestine flag on its neck.

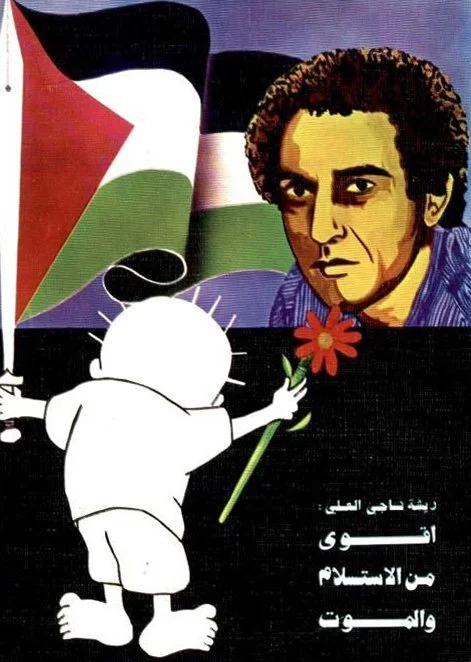

Handala & Naji al-Ali

After his family was displaced from his family’s Al-Shajara village in Palestine during the 1948 Nakba when he was a child, Naji al-Ali had started experimenting with art in Beirut. He tried to find a unique way to have his art communicate the Palestinian experience, including using materials like mirrors to involve the viewer.

However, he eventually abandoned painting as a medium and instead became a political cartoonist in the 60s – a leap he was encouraged to make by Ghassan Kanafani, a Palestinian writer who had came to Beirut in 1960.

Not only did switching paths free Ali up from his menial jobs to make some money, but it changed his way of communication. Kamal Boullata wrote in Palestinian Art:

“Ali saw his cartoons as a communicative form of expression that allowed him to integrate verbal and visual means without the affectations that plagued 'art' in his environment.

As cartoonist for the widely read Kuwaiti dailies al-Siyasa and al-Qabas and the Beirut daily al-Safir, he achieved widespread popularity, reaching thousands of readers throughout the Arab world on a daily basis. With biting humour, he summed up the position of the common Palestinian of the refugee camp vis-à-vis the endless political compromises reached in the region.”

Handala (حنظلة) character

– also written as Handhala, Hanzala, or Hanthala

Created by Naji al-Ali

Ali would go on to become known for his cartoon character of Handala, a perpetually 10-year-old boy representative of Ali himself. Specifically, the age refers to the age he was when his family was displaced in the Nakba.

The character in its final and most-well known form, with his back to the viewer, started in 1973 after the October war that year. It showed Ali’s disdain for political actions of foreign nations for Palestinians.

The name connects to a local Palestinian plant – Handala in Arabic, or Colocynth in English – which bears bitter fruit. Its deep roots ensure it always grows back when cut, making it a metaphorical symbol for Palestinians. As described in Middle East Eye:

“For centuries, Palestinians have used this plant as a metaphor for their deeply rooted connection to their land, as well as their strength and right of return.

The plant became a symbol which personified the pain and loss of displaced refugees following the Nakba, with its thick and deep roots representing their link to their land.”

Sept 1983 - A group of fish swim with the key of the right to return that is a important symbol for Palestinian refugees to return to their land. As the PLO flees Beirut following Israel’s invasion into Lebanon, the fish go the opposite direction, as a critique of the PLO leadership in their ability to reach liberation.

Cartoon by Naji al-Ali

Sept 1983 - Arab leaders, in the form a football team, don the U.S. flag on their uniforms as the player kicking has 242 on him to represent the UN Resolution of the same number from 1967 – trying to score on a blocked Israeli goal filled with bricks.

Cartoon by Naji al-Ali

In the 1980s, Ali had been detained by Israeli Occupation Forces during the invasion of Lebanon, and soon was displaced briefly to Kuwait in 1984 before then being displaced again to London in 1985. His life was often under threat.

He criticized everyone: Arab governments, the PLO – and of course Israel and the US. He gained widespread attention for his work.

November 1980 - A resistance fighter puts his hand into the now-dry homeland surface, as his blood waters the soil.

Cartoon by Naji al-Ali.

January 1987 - Barbed wire restricts and confronts a Palestinian woman wearing a traditional tatreez pattern and nestling a keffiyeh in her lap. Tears fall as she holds a flower.

Cartoon by Naji al-Ali

July 1980 - While movies come to an end, the Palestinian suffering and struggle is ongoing for all ages.

Cartoon by Naji al-Ali

In August 1987, Ali was assassinated while walking to work at the London office of al-Qabas newspaper, a publication he had worked for as a political cartoonist. The still open case technically remains “unsolved” to this day. (There is some speculation it was even a PLO attack, as Ali had received a call from within the organization after he was critical of their leadership in his cartoons.)

Ali may have become a martyr, but the life of Handala as a symbol for Palestinians would continue to make an impact.

The Pen of Naji Al Ali

Poster by Ghazi Inaim, 1987

via Palestine Poster Project