Part 2 -

Palestinian Art History

Nakba: A Defining Time

1947 - 1950

Mostly historical information to provide context around a time that changed everything for Palestinian life altogether: the 1947 UN Partition plan and 1948 Nakba.

World War II

During the second world war, less than three decades after the first, Germany carried out a holocaust of six million Jewish people. It was, unquestionably, a tragedy.

Jews who fled persecution from the late 1930's through the early-to-mid 1940's were admitted – in limited numbers – to countries such as Spain, Switzerland, Portgual, and the United States. Many also attempted to go to Palestine.

After WWII officially ended in 1945, there was also the question of where all of the displaced Jewish people would go. At this time, the U.S. tried to persuade Britain to allow 100,000 of the ~250,000 total displaced Jews to go to Palestine, which was rejected.

Over this period, Britain went through a series of attempts to figure out next steps as they tried to temper the waves of illegal immigration and the Arab response to it.

Ultimately, they weren’t able to find an agreed-upon solution. As a result, they decided to pass the responsibility on to the United Nations.

UN Partition Plan

The United Nations had been created in 1945, succeeding the League of Nations, under the declared goal of protecting international peace and security.

In 1947, the UN General Assembly passed Resolution 181. This got rid of the British Mandate on Palestine, replacing it with a plan for partitioning the land into two states – an Arab and a Jewish state. (This also included declaring Jerusalem and Bethlehem as part of an international zone and to be administered by the UN.)

At this time, Jews owned about 6% of the land and were barely a third of the population. However, the UN partition allocated them 56% of land.

There was immediate pushback that the amount allocated for the Jewish state was unjust. Hundreds of thousands of Palestinian Arabs (both Muslims and Christians) would be forced to live in this Jewish State. It would also leave the designated “Arab State” without important agricultural lands and seaports.

The decision was rejected by the Arab community, who still wanted an independent, singular, and self-governing state – including full rights for both the country’s Arab majority and for the Jewish people who had already been there as legal citizens.

The plan continued in spite of the opposition. As the Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question notes, “it gave international legitimacy to the Zionist conquest of Palestine by force of arms.”

Beginning of the tragedy

Painting of the Nakba later on by Ismail Shammout, 1953

via artist archive

Nakba

Immediately after the UN plan in November 1947, Zionist forces began to target Arab villages and residential quarters.

This included forcibly displacing Palestinians from their homes both within the new “Jewish State” lines and outside of the UN border lines.

Zionist had several militias ready to fight and had already been importing a massive amount of arms throughout the British Mandate period. Palestinians, on the other hand, had no major official fighting groups at this time.

In the Spring of 1948, attacks ramped up dramatically after the official adoption of Plan Dalet, which was essentially a call for ethnic cleansing of indigenous Palestinian Arabs through the destruction of villages.

One of the most notable attacks was the Deir Yassin massacre at the start of April 1948 that left over 100 Palestinian martyrs. This was also used as a Zionist propaganda tool to spread fear. They wanted to get as much land as possible before the British Mandate reign officially ended, so they continued to attack villages.

Massacare of Dair Yaseen

Painting later on by Ismail Shammout in 1955

via artist archive

On May 14, 1948, the British forces withdrew. Afterwards, the “Declaration of the Establishment of the State of Israel” was announced by David Ben-Gurion, the first Israeli Prime Minister and former head of the World Zionist Organization. The United States also recognized the “State of Israel” on the very same day.

Neighboring Arab countries, who were harboring many refugees, went to war with Zionist forces after the self-proclaimed state declaration. Fighting continued into 1949, ultimately to no avail. By the end, more than 500 villages and 10 cities were depopulated. There were invasions, bombings of homes, looting, and destruction all around these areas.

This period of ethnic cleansing is referred to as Al-Nakba, which loosely translates as “The Catastrophe” from Arabic to English – though that does not do sufficient justice to what happened. (It is often referred to in English-language context just as the Nakba.)

15,000 were martyred and over 750,000 Palestinians (around two-thirds of the Arab population) were ethnically cleansed from their homes to either refugee camps within Palestine or to other neighboring countries like Lebanon, Jordan, and Syria.

Expulsion from the Homeland

Painting of the Nakba later on by Abed Abdi in 1967

via artist archive

Zionists had taken up 78% of historical Palestine. Overall, there was over four million acres of Palestinian land estimated to be stolen at this time.

There were around 150,000 Palestinians who remained inside the “Israeli” borders after, a quarter of whom were internally displaced. These Palestinians were technically given “Israeli citizenship” but lost most of their land and were subjected to a violent rule after.

From the territories remaining outside of these “Israeli” borders, those did not even become an independent Palestinian state either. Egypt took control of the Gaza Strip and Jordan took control of the West Bank and East Jerusalem, both places then becoming home to many refugee camps.

In December 1949, the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA) was established. In what was supposed to initially be a temporary program, the UN sought to provide temporary humanitarian assistance, education, work programs, refugee camp infrastructure, and more. However, this was a drop in the bucket after the damage of the UN Partition decision that led to the nightmare in the first place.

In addition to the immense human tragedy, Kamal Boullata writes about the impact of the previously-growing art scene after the Naka:

“Much of the art objects produced over the four decades preceding those bloody months were rendered irretrievable in the wake of the victors' widespread looting.

All traces of the cultural enterprise of Palestinian modernity were obscured, as its advocates were dispersed and the accomplishments of a century and a half of development in a native pictorial art were doomed to oblivion.”

Following The Catastrophe

1950 - 1967

How art took a new form in rebuilding after the Nakba, led by artists such as Ismail Shammout and Tamam Al-Akhal, and started to become integrated into organizations like the PLO and groups of freedom fighters.

After The 1948 Nakba

With nearly a million people displaced from the Nakba and many Palestinians now navigating a new life in refugee camps, life was forever changed.

Art – along with work, education, and culture – naturally came to an initial stop in the wake of this devastation.

In her book Liberation Art of Palestine: Palestinian Painting and Sculpture in the Second Half of the 20th Century, Samia Halaby describes the nation-defining event as one that “shaped the consciousness of the new generation of (Palestinian) artists.”

“They emerged from the tragedy ready to rebuild, but what they would rebuild was not known through their own experiences. To many, memory seemed to begin anew. Artists thought that everything they did was being done for the first time. To them the first show after 1948 seemed the first show ever, and the art of painting and sculpture after 1948 was wholly new to Palestinian history.”

Halaby also notes that Palestinians felt it was important to preserve the stories of the Nakba and their cultural history.

The First Steps After

Around five years later, a new era and generation of visual art for Palestine started. A defining point was a 1953 exhibition in the Gaza Strip that featured the work of a 23-year-old painter, Ismail Shammout.

At 14-years-old, Shammout’s family had been expelled from their village during the “Lydda Death March” of the Nakba, where Palestinians were not allowed to carry water. His two-year-old brother did not make it from the dehydration. After being at a Khan Yunis refugee camp in Palestine, Shammout found a way to go study in Egypt. He was still a student in Cairo at the time of this show.

This 1953 exhibition included a painting by Shammout of an old man walking with children – entitled Where To? – that would immediately gain attention. It was inspired by his own experience being displaced with his parents and siblings.

Where To?

Painting by Ismail Shammout, 1953

via artist archive

It was one of several paintings that brought the pain from the Nakba into visual depictions and immortalization. Refugees saw themselves in the work and the art was well-received. Shammout had another exhibition in Cairo the following year and a new chapter had begun.

Kamal Boullata sees this approach as a contrast to the Palestinian painters under British Mandate, like Nicola Saig, who used historical moments to metaphorically comment on current conditions. After the ‘48 Nakba, memory was instead used to express the experience of exile.

Ismail Shammout (right) at a follow-up exhibition in Cairo in 1954

via Palestinian Art book

Samia Halaby writes that the 1953 exhibition “marked the beginning of the liberation movement in its artistic form and was followed by a flood of individual and group shows by a new generation of artists.”

During this time, artists were also still able to travel across the West Bank, Gaza, and neighboring countries – like Amman in Jordan – all of which were under Arab sovereignty for the time being.

Al Quds remained a prominent area for the arts, and was where many artists came to in the late 1940s for those still in Palestine.

There were also patrons, such as Amineh El Husseini, who helped to support and promote young artists. Some of them formed clubs and groups who would exhibit together.

However, many Palestinians were also taking refuge in other countries – especially those displaced from villages in the ‘48 territories that had been taken over by Israeli Occupation Forces. In other countries nearby, like Lebanon and Jordan, refugee camps and communities formed there as well. These would also become locations of art scenes developing.

Art was seen by some as a way to implicate international viewers to at least force them to witness the tragedies of the Israeli crimes against the Palestinian people.

Beirut As Refuge

Kamal Boullata writes in his book, Palestinian Art, that this initial time of art development after the Nakba aligned with Beirut’s heyday as the “metropolis of Arab modernity.”

“1952 marked the outbreak of the Egyptian revolution, one of the first major direct consequences of Palestine’s fall and an important factor, through its nationalist and anti-imperialist policies, in the subsequent coups d'état in neighboring Syria and Iraq as well as in the political unrest in Jordan and Lebanon.”

In that same year, Lebanese art collector Nicolas Sursock left his large residence and collection to the city, in order to establish Lebanon’s first museum of contemporary art. The space in Beirut would go on to open its doors officially in 1961. During this time of the 1950s and 60s, galleries sprang up around Beirut to showcase work from artists around the city, art from the Arab world, and some from Europe and the U.S.

Beirut by Ismail Shammout, 1957

Palestinians in exile in Beirut included the aforementioned Ismail Shammout, who ended up going to there in 1956 to work at the UN Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA), where they established an office for commercial art and book design.

There was another Palestinian artist, Tamam Al-Akhal, who Shammout had exhibited with in 1954. She received a Teaching Certificate in Fine Arts in 1957 after studying on scholarship in Cairo. Al-Akhal then ended up in Beirut, where she began teaching art at a female-only college.

Refugee camp in Beirut by Tamam Al-Akhal, 1960s

In 1959, Shammout and Al-Akhal got married while both in Beirut. Together, they would continue to play an important and evolving role in Palestinian art for years to come.

Self-portrait

Painting by Ismail Shammout, 1957

via artist archive

Tamam (Al-Akhal)

Painting by Ismail Shammout, 1965

via artist archive

PLO Start & Embrace of Art

After years of deliberation on next steps among Arab nations, a meeting of a Palestinian National Congress in 1964 resulted in the establishment of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO).

This included a National Charter for the PLO, which emphasized the connection between the national-Palestinian and the pan-Arab dimensions of the struggle for Palestine's liberation. As The Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question writes about the charter:

“It declared the Balfour Declaration, the Mandate, the partition of Palestine, and the creation of Israel null and void, and saw in Zionism ‘a movement that is colonial in its emergence, aggressive and expansionist in its aims, fanatically racist in its nature.’

It called for the restoration of Palestine to ‘a condition of legitimacy’ and to enable its people to exercise national sovereignty and national freedom.”

Immediately after, the PLO opened an exhibition of artists in Al Quds to celebrate. “The show had such an impact that people began to think of art as part of the liberation movement,” writes Samia Halaby in her book, Liberation Art.

A year later, in 1965, the Arts & Culture department was founded with Ismail Shammout and Tamam Al-Akhal leading its efforts.

The first PLO logo created by Ismail Shammout, 1965

This included creating posters, which were becoming an increasingly popular art, marketing, and propaganda form. The Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question writes:

“Shammout designed the first set of posters ever issued, a total of four, with the caption ‘We All Are the Sons of Palestine.’ The posters communicated the simple message that the PLO was the representative of the Palestinian people and that it was a political body emerging from the masses. The same designs were reprinted in 1967 with the caption, ‘We All Are with the Resistance.’

While some artists donated labor, others were remunerated and some were employed in the organization and management of events. They produced and promoted films, photographs, reportages, pamphlets, and posters; the latter were the most effective, lightweight and low-cost means of visual and iconographic communication.”

The PLO Art Department also helped organize exhibits for Palestinian refugee camps, who would otherwise never make it into the art market or commercial galleries.

And since few Palestinian artists in Beirut were able to make a living from their art alone, most took on jobs that included teaching at UNRWA schools, working on construction sites, or freelancing in commercial art.

These Palestinian refugee camp artists included Ibrahim Ghannam, Yusif Arman, George Fakhoury, Imad Abd ar-Wahab, Jamal Gharibeh, Tawfiq Abdel Al, Muhammad al-Shair, Abd al-Hai Musalim, Husni Radwan, Michel Najjar, and more.

Don't Forget Palestine

Poster by Ibrahim Ghannam, 1955

One of the earliest designs in the Palestine Poster Project archive

An Era of Poster Art Kicks Off

While there were some posters in the 1950s for Palestine, the medium became powerful in 1965 after the PLO launched their poster designs and other groups started to follow suit.

Like with Ismail Shammout, groups brought in Palestinian artists to do designs. Some also made separate posters on their own.

For Palestine - Palestinian National Fund

Poster by Ismail Shammout, 1965

via Palestine Poster Project

Palestine Liberation Army Is A School

Poster by Abboud, 1965

via Palestine Poster Project

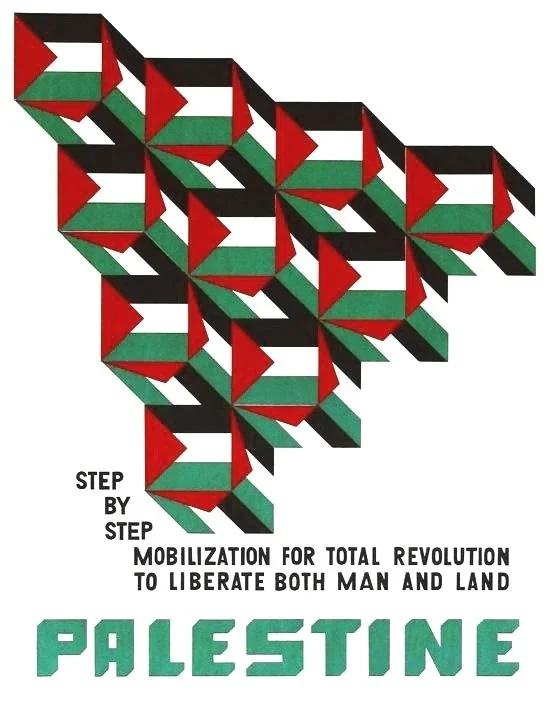

Step By Step

Poster by Samia Halaby, 1970

via Palestine Poster Project

Solidarity - Vietnam - Palestine - Rhodesia - South Africa - Latin America - GUPS (General Union of Palestinian Students)

Poster by Kamal Boullata, 1969

via Palestine Poster Project

1968’s Battle of al-Karama

Artist unknown, 1968

via Palestine Poster Project

Toiling Arab Masses

PFLP Poster by Vladimir Tamari, 1970

* Tamari also designed the PFLP logo, which Ghassan Kanafani gave his stamp of approval

via Palestine Poster Project

Even Ghassan Kanafani designed some of his own posters for the PFLP.

For the feyadeen that appeared in many posters of this initial period, Kanafani wanted to make it clear they were not terrorists but rather freedom fighters.

Shattered the Fascist Tanks

PFLP poster by Ghassan Kanafani, 1970

via Palestine Poster Project

Steadfastness of Gaza

PFLP poster by Ghassan Kanafani, 1970

via Palestine Poster Project

Variations in Expression

There were a mixture of artists trying other techniques and styles, such as a young Naji al-Ali, but there was one woman who stood out in particular.

Juliana Seraphim was 14-years-old during the ‘48 Nakba, when her family came to Beirut. They were able to attain Lebanese citizenship, which was not common with other refugees.

After turning 18, she worked as a secretary at UNRWA. At the same time, she took evening art classes with Lebanese painter Jean Khalifé, who later set up Seraphim’s first exhibition in his own studio.

She also spent time studying at the Lebanese Academy of Fine Arts and in 1959 before spending a year each in Florence, Italy and Madrid, Spain – after which she came back to Beirut. In 1961, she participated in the first exhibit at the Sursock Museum, Lebanon’s first contempoary art museum.

Painting by Juliana Seraphim, year unknown

In particular, her intention was different from the art of Ismail Shammout and others who wanted to specifically tackle the Palestinian liberation cause in their work and communicate to the masses.

Instead, Seraphim chose to use art as a medium for self-discovery and revelation. She once said: “I do not differentiate between art and life. Through art I find love, and through love I find my freedom.”

While she did not address Palestine more explicitly in her work, she did however still draw on inspiration of experiences from her childhood. In particular, she had strong memories of the Mediterranean Sea by Jaffa, where she grew up, or her grandfather’s home in Al Quds.

Painting by Juliana Seraphim, 1964

Her surrealist work was filled with dream-like imagery that had themes tied to spirituality, nature, sexuality, and more. The ‘60s were just the beginning, as her already recognizable style started to evolve further in the upcoming decades.

Painting by Juliana Seraphim, 1960

Lack of Moving Images

After Palestinian cinema had started to get its footing in the 1930’s and 40’s, that quickly came to a halt in 1948.

The time from Nakba to Naksa, ‘48 - ‘67, is looked at as the “Epoch of Silence” for Palestinian films.

However, refugees in exile did make and contribute to other films. This included the first two Jordanian feature films. Ibrahim Hassan Sirhan created Sira' fi Jerash (Struggle in Jerash) in 1957 and Abdallah Ka’Wash made Watani Habibi (My Beloved Country) in 1964.

Naksa: Further Occupation

1967 - 1970

Mostly historical information to help provide some context around how the years after the Nakba in 1948 led to the Naksa in 1967 – and the first few years that followed. Plus, some art developments after the initial impact.

A Palestinian figure looks on at the land sometime after the Nakba, undated

Photo via UNRWA archive

The Decades Leading Up To 1968

For the 750,000 Palestinian refugees from the Nakba, many hoped to come back to their homeland. After all, UN Resolution 194 had affirmed the refugees’ right of return under international law.

However, that right of return would not be honored by the occupiers. Not only that, a law by the new “state” was passed in 1950 to give the right for Jews and their spouses to come to Israel and acquire citizenship if they had one or more Jewish grandparent.

For Palestinians, they could not come back to their homeland. Anyone who tried also faced grave danger. Between 1949 and 1956 alone, Israeli soldiers shot several thousands of Palestinians who continued to try to cross the border back into their own country. However, some managed to be able to sneak in, raising the Palestinian Arab population by an increase of about 30% again in the early 1950s.

One of the first kindergarten classes in Dikwaneh camp, Lebanon, directly after the 1948 Nakba

Photo via UNRWA archive

For those who had stayed in their homeland after the Nakba in ‘48, they were supposed to be treated as citizens with full rights. However, the Israeli imposed a military rule over Arabs, using discrimination to keep strict control over movement of people and organization, including striking down any efforts to resist repressive policies. Any independent collective action – public, social, or cultural – was banned.

Palestinian Arabs were also isolated in select villages and towns as the Israeli miliary aimed to take over more land. In 1959, some of the restrictions slightly lessened as the Zionist occupiers needed more workers they could cheaply pay, which required an increase in freedom of movement.

Young women play basketball at the Women's Activity Centre in Kalandia, West Bank, 1950s

Photo via UNRWA archive

Arabs were treated as inferior, with limited rights. Israeli military permission was needed for anything from education to health care to commerce, and even marriage or divorce. Israel controlled their life with a strict occupation.

And for those in exile, refugee camps were difficult as well. As UNRWA notes: “The lives of the refugees were turned upside down; they were faced with disease, lack of food and water, life in unfamiliar places and overcrowding.”

Palestinian refugees arrive in East Jordan, 1968

Photo via UNRWA archive, by George Nehmeh

Fighting for Liberation

Israeli Occupation Forces continued massacres of Palestinian Arabs in the country.

In 1953, for example, massacres included attacks on Qibya in the West Bank and al-Bureij refugee camp in Gaza – leaving over 100 Palestinian martyrs in the process.

Israeli soldiers would keep targeting these areas in the years that followed, like in 1956 when hundreds of Palestinians were martyred in Gaza during Israeli attacks in Khan Yunis and Rafah.

A depiction of a 1956 Israeli massacre in Khan Yunis, Gaza, on November 3, when hundreds were martyred by Israeli soldiers

Painting by Tamal Al-Akhal later in 1963

via @atlajala

Organizations like the UN Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) continued to provide assistance on certain levels – such as with shelter, food, medical aid, education, work programs, and more – but it didn’t change the fact that there was a military occupation.

Palestinian students in the Auto Mechanics course at UNRWA's vocational center in Gaza, undated

Photo via UNRWA archive

In order to combat continued Israeli aggression, Palestinian armed resistance fighters – otherwise referred to as “fedayeen” at this time – formed paramilitary groups around the early 1950s to be able to defend their people and homeland.

This also evolved into a more formal Palestinian fighting organization that would be independent from Arab governments. Thus, Fatah was born in the late 1950s, its name an Arabic acronym in reverse for “Harakat al-tahrir al-watani al-Filastini” which translated to “The Palestinian National Liberation Movement” as part of its self-declared mission. Yasser Arafat was one of its founders. As The Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question notes:

“Fatah was the first national liberation movement since 1948 to be started by Palestinians themselves and that brought together Palestinian activists from different ideological and intellectual backgrounds. It called on all politically active Palestinians to abandon their party affiliations and to be united under its banner as a movement to ‘organize a vanguard that would rise above factionalism, whims and leanings to include the entire people.’

The Arab nationalist slogan prevalent at the time was ‘Arab unity is the path to the liberation of Palestine.’ Fatah reversed it, contending that ‘the liberation of Palestine is the road to Arab unity’; it acknowledged the pan-Arab dimension of the Palestinian cause but insisted that the Palestinian people had to rely on themselves in their struggle for liberation. For Fatah, the Palestinian revolution would be ‘Palestine in origin and (pan) Arab in its development.’

The movement's leadership saw armed struggle as its primary means of liberating Palestine. It modeled itself after the revolutionary struggles in Algeria, Cuba, and Vietnam.”

الكرامة ١٩٦٨ (Dignity, 1968)

Poster for Fatah

Designed by Al Muhandis Shukri, 1968

via Palestine Poster Project

Revolution Until Victory

Poster for Fatah

Designed by Kamal Boullata, 1969

via Palestine Poster Project

Cells of Fatah began to form in Gaza – but also in Jordan, Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, Kuwait, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia.

At the same time, there was also an interest by others to create a Palestinian political entity. This came to fruition with the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) after a Palestinian National Congress was called in June 1964.

The PLO was officially recognized at the second Arab summit that September, though with the explicit agreement they would not try to arm Palestinians in Jordan or attempt to gain sovereignty from Jordan in the West Bank.

“The establishment of the PLO prompted Fatah in particular to accelerate the consolidation of its presence on the ground, by establishing its military wing, al-Asifa (the Storm), and launching its first military operations in January 1965,” notes The Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question.

One of the several West Bank refugee camps in the 1950s

Photo via UNRWA archive

1968 Naksa

Since the Nakba in 1948, Israel had continued to fight against the neighboring Arab countries – especially since the West Bank was under Jordanian sovereignty and the Gaza strip under Egyptian sovereignty.

This included attacks against in Egypt in 1956 (with Britain and France as Israel’s allies) and diverting the Jordan River in 1963 (with Syria as Jordan’s ally).

In June 1967, Israel started a new stage by launching a surprise attack on Egypt. More attacks followed that were primarily against Jordan, Syria, as well as within Palestine.

In what is sometimes referred to as the Six-Day War, Israeli Occupation Forces took control of the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and the Gaza Strip. They also took control of the Sinai Peninsula from Egypt and the Golan Heights from Syria.

This became known as Al-Naksa, which translates to the setback.

Israeli Occupation Forces driving towards the Dome of the Rock at Al-Aqsa Mosque in 1967

Photo via Getty Images

The Naksa displaced another 300,000 Palestinians from their homes – including some who had already been expelled during the Nakba – bringing the total to over a million Palestinians driven out of their homes between 1948 and 1967.

The overwhelming majority of the newly displaced Palestinians sought refuge in Jordan. Many crossed into Jordan through the river, and did so on foot with very few belongings.

Palestinians forcibly displaced across the Jordan river on the damaged Allenby Bridge in 1967

Photo via UNRWA archive

The size of land that now made up “Israel” had significantly grown and the entire historical Palestine territory had now been seized. On the eve of the initial June 5 attack, Israeli Labor minister Yigal Allon wrote: “We must avoid the historic mistake of the War of Independence (1948)… and must not cease fighting until we achieve total victory, the territorial fulfillment of the Land of Israel.”

Their intention was clear: to fully take control of all the land, so there could be no Arab sovereignty in any territory. The Zionist mission to establish a so-called “Jewish state” at the harm of the local Palestinian Arab population was in full force.

صمت البحر

(Silence of the sea)

Artwork by Abed Abdi, 1969

Immediately after, UN Resolution 242 called for a withdrawal of Israeli forces from territories occupied during this battle, among other requests.

Israel not only ignored the UN, but they actively encouraged and supported Zionist settlers to move into these areas, building homes on land they did not own. This went directly against international law.

They also illegally annexed East Jerusalem and different parts of the West Bank, which they self-deemed part of the “state of Israel” – which was not recognized as true by the internal community.

The feyadeen resistance fighters who had already formed became even more determined in armed struggle, feeling a heightened need to take Palestine back as there was insufficient help from the rest of the Arab world or extended international community.

The Halo

Painting by Ismail Shammout, 1969

via artist archive

As The Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question writes:

“The defeat brought about the realization that counting on the Arab regular armies was unrealistic and that the Arab governmental approach exemplified by the creation of a PLO of notables was unlikely to yield positive results. The Palestinian national struggle was liberated from the bonds of official Arab sponsorship.

The phenomenon of guerrilla action became widespread, and new Palestinian organizations were formed. The fierce resistance demonstrated by the Palestinian fighters and the relatively heavy losses suffered by the Israeli army in the Battle of al-Karama in March 1968 significantly boosted the movement, leading to the enrollment of thousands of Palestinian (and Arab) volunteers and setting the stage for the transfer of PLO leadership into the hands of the guerrilla organizations, especially the most powerful among them, Fatah.

This was achieved at the fourth session of the PNC, held in Cairo from 10 to 17 July 1968. There a new Palestine National Charter was approved, devoted to Palestinian nationalist (rather than pan-Arab) ideas. The fifth PNC session, held in Cairo in early February 1969, further solidified this trend with the election of Fatah leader Yasir Arafat as chairman of the PLO Executive Committee, a position he was to hold until his death in 2004.”

In addition to Fatah taking the lead of the PLO after the defeat in 1967, other factions also continued to pursue their efforts. The Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) was also formally organized around this time and initially became a faction of the PLO in the late 1960s. The group itself split soon after, and the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine (DFLP) was born from the separation of members due to differences in strategy.

Art featuring a split rendition of the Dome of The Rock and featuring Arabic text

by Jordanian ceramicist Mahmoud Taha, in support of Palestine

Amman’s Refugee Art Community

The 1967 events only further pushed artists to get more serious – both in Palestine and in neighboring countries – to make work about the Palestinian struggle.

Amman, Jordan – where many displaced from the Naksa fled – then also became a home and center for Palestinian artists in exile. It didn’t take long for there to be exhibitions with themes of liberation, appearing in Amman as soon as 1968.

Jordanian ceramist Mahmoud Taha said that "it was not possible to show artwork that had no connection to the movement.”

A 1969 exhibit in Amman, making the Battle of Al Karameh from the previous year, featured many types of art – children's drawings, photographs, paintings, sculptures, maps, prints, books, records, songs of the revolution, stamps, clothes, and more. It featured artists from all over the Arab world and other international countries.

Beirut and Amman both played important roles during this time for those displaced outside of the country.

Palestinian refugee children play outside their tent school in Ghor Nimrin camp, Jordan

Photo via UNRWA aarchive

In Palestine, with the homeland entirely taken over, there was one shift in particular that impacted artist relations. Those in Gaza and the West Bank and previously been unable to have contact with those in the territories taken over as part of the ‘47 UN Partition and ‘48 Nakba. However, once again, artists across all these areas were able to have communication, for the time being.

Palestine Film Unit

After establishing the Art Department of the PLO in 1965, there were more additions to come.

The Palestine Film Unit (PFU) came in 1967 to make films that took back the narrative into their own voice. The goal was to document the revolution and create a historical archive.

It was done in conjunction with Fatah, making it the first cinema unit working under a Palestinian military organization.

Sulafa Jadallah and Hani Jawharieh at the Battle of Al Karameh in 1968

Photographer unknown

Leading this department were filmmakers Mustafa Abu Ali, Hani Jawharieh, and Sulafa Jadallah.

Mustafa Abu Ali had just graduated in 1967 after studying in the US and UK. He stated at the time that “the Palestinian resistance believes that action through cinema is a natural extension of armed action.”

Sulafa Jadallah had also studied, but closer to home. She was the first woman admitted to the Higher Institute of Cinema in Cairo, where she excelled. Jadallah is also referred to as the first female cinematographer in the Arab world in general.

Jadallah’s impact was significant, but her career was cut short in the middle of 1969 when she was unfortunately hit by friendly fire. She survived but was unfortunately paralyzed, never able to shoot a film again.

Photo by Film Unit leader Hani Jawharieh

Hani Jawharieh was involved with both the Film Unit as well as the PLO Photography archive.

Samia Halaby writes about his role in her book, Liberation Art of Palestine:

“Jawharieh was the first photographer to accompany Palestinian freedom fighters to the Jordan River Valley during the late 60s.

In 1967 he created a film called Exodus (different from the American film of the same name), which told of the evictions of the Palestinians from their homes and lands during the war of that same year.

Many of the films, which he made in Jordan just before leaving to Beirut, document the destruction by Israel of agricultural lands in the Jordan Valley. These films were followed by a series of films and photographs documenting the life and struggle of the Palestinian refugee.”

In 1970, filmmaker Jean Luc-Godard – a pioneer of the French New Wave movement – traveled to Amman, Jordan to spend time with their team at Palestinian refugee camps. While there, he and colleague Jean-Pierre Gorin also captured footage that was supposed to be a film about feyadeen.

However, Black September – otherwise known as the Jordanian Civil War between Jordan and the PLO – led to mass casualties. This included many of the fighters who had been the focus of Godard’s documentary, and he ultimately abandoned the project. (The footage was later re-purposed in his experimental film Ici et ailleurs, or Here and Elsewhere.)

Still from Jean-Luc Godard’s footage of Palestinian feyadeen

With the Film Unit, “After the horrific events of Black September, Mustafa Abu Ali, along with the rest of the PLO left Jordan and went to Beirut. Hani Jawharia and Sulafa Jadallah were (at the time) unable to get out of Jordan,” wrote Emily Jacir in a later article for The Electronic Intifada.