Part 1 -

Palestinian Art History

Traditions & Innovations

1800 - 1914

A starting point to look at the history of Palestinian art from information that is available and work that is documented. Including how art began to change within a religious framework at the turn of the 20th century, leading up to World War I.

The Painting of Icons

In the book The Origins of Palestinian Art, Bashir Makhoul and Gordon Hon say that they do not consider Palestine, nor Palestinian art, to have a fixed origin in time – an exact moment to point to as the moment of creation.

Instead, how far back we go is just dependent upon the information available from history, they essentially say. In Palestinian art literature, typically the 1800s are considered a good place to begin, they say, considering that we have an understanding of some of that era.

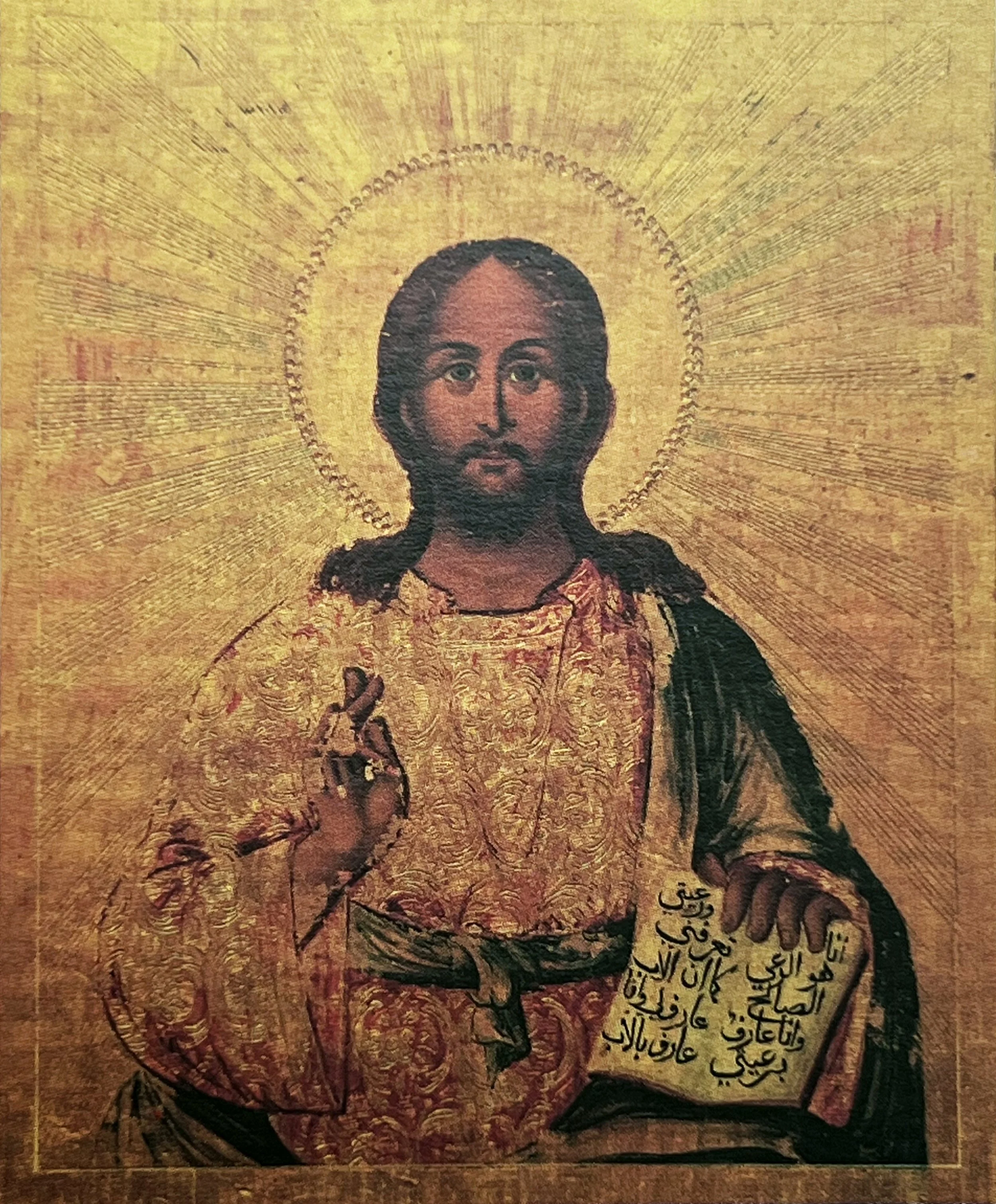

Christ Pantacrator from the Arab Orthodox Church

Artist unknown

via Palestinian Art book

At the time of the 19th century, artists were following a long tradition of pictorial painting icons and portraits, especially in Al Quds (Jerusalem). In Kamal Boullata’s book, Palestinian Art, he writes:

“The tradition of Byzantine icon painting, whose craft and precepts were formulated by the end of the fifth century, was the major pictorial living tradition handed down the ages throughout the Mediterranean world.

The seventeenth century, which marked the decline of this thousand-year-old painting tradition, heralded the beginning of a renaissance in Arab regional schools of religious painting whose iconographic language was borrowed from Byzantine models.”

Artists from the Jerusalem School followed the Byantizine tradition of icon painting, but The Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question writes they adapted it by using “characteristic features of the Arab folk hero in the popular arts and Islamic miniatures flourishing in Arab visual tradition.”

Icons made at the Jerusalem School were part of homes of the Arab Orthodox community in Palestine and the churches they frequented, as well as throughout The Levant. Additionally, Boullata notes, small icons were sought by those who traveled from the Ottoman Empire. The iconographers were also commissioned by convents and monasteries in Lebanon and Syria to do painting and restoration assignments.

“The painters took pride in signing their icons in Arabic with the first name usually appended by al-Qudsi, meaning the Jerusalemite,” writes Boullata, with Al Quds being the Arabic name used to describe the Old City. He also says that artists in some cases went by al-Urushalimi, “which is the biblical title identifying a Jerusalemite.”

This included Hanna al-Qudsi, who reportedly did this first, as well as others such as Mikha'il Muhanna al-Qudsi or Yuhanna Saliba al-Qudsi.

Paintings of Mikhail Muhanna al-Qudsi from 1882 – Saint George (left) and The Virgin Mary (right)

Artist unknown

via Palestinian Art book

In writing about this tradition, Boullata shares some wider historical context:

“The principal contributing factor to the Arabization of the Byzantine icon was the deteriorating relationship between the Arab adherents of the Orthodox Church and the clerical hierarchy successively headed by Greek patriarchs who kept total control of church affairs while the Church's Arab clergy and parishioners were neglected.

The Arabized icon was thus a form of expression of independence from Greek control of the Church that had been consolidated by the Ottoman authorities ever since they took over the region in the sixteenth century. The development in icon painting further coincided with the growing awareness of national identity in the provinces that had fallen under Ottoman rule.

In fact, when the first Arab Orthodox Patriarch was elected in Damascus in 1899, the event was considered by cultural critics from the region as a groundbreaking victory for Arab nationalism.”

This period and transition of how the art was created and identified – and what it represents – was, in Boullata’s eyes, “the indigenous beginnings of a personalized form of painting in Palestine.”

An Invention: Photography

While icon painting may have been around for centuries, there was a new visual art format that developed in the 19th century.

In 1839, the daguerreotype photography approach was invented and introduced to the public by French artist Louis Daguerre, which was the first publicly available photo process.

Later that same year, French painter Frédéric Goupil-Fesquet came to photograph the Old City. Many Europeans did the same during the rest of the century, who primarily were interested in photographing holy sites.

Before that point, people only had access to reading or seeing drawings and paintings of well-known places around the world. In this case, these photos held notable interest to many as a holy site.

Dome of the Rock at Al-Aqsa Mosque

Photo by French photographer Maxime Du Camp in 1850

During this time, photography was also picked up as a craft locally. Around 1860, the first photo studio was started by an amateur photographer named Yessai Garabedian, a priest who would soon become the Armenian Patriarch of Jerusalem.

The students of the school became the first local photographers in Palestine. The most notable early example was Garabed Krikorian, an Armenian-Palestinian who would go on to open his own studio. Krikorian also trained Khalil Raad, who was born in Lebanon originally. Raad is considered the first Arab photographer to gain recognition in Palestine. More continued to follow in their footsteps.

Photo by Khalil Raad, 1876-1918 collection

via Institute for Palestine Studies

Photo by Khalil Raad, 1876-1918 collection

via Institute for Palestine Studies

A Secular Shift

Nicola Saig – also written as Nikolas Saig – is viewed as the earliest well-known Palestinian artist, according to the later writing of artist Ismail Shammout.

Saig was one of several early Christian and Muslim painters in Palestine who started as iconographers, continuing the tradition of the 19th century.

However, these artists also started to create religious paintings that were no longer in the form of icons specifically, while still maintaining a sense of the history and tradition.

The Conversion of Saul

Painting by Nicola Saig, year unknown

Towards the end of the 1800s and early 1900s, this shift ultimately led to artists painting secular (non-religious) pieces as well.

Part of the inspiration for this shift was due to influence from Russian painters, who had been bringing their own dynamic to icon painting. They noticed how those painters living there at the time drew inspiration for their religious paintings from the local scenery and how the figures in their paintings drew on the local people, embracing Arab features. Catholic painters who had came from Rome to local convents also made an impact.

In The Origins of Palestinian Art, Bashir Makhoul and Gordon Hon write about how quickly this happened – noting it was “extraordinarily abrupt compared to the history of painting in Europe, where centuries of painting had elapsed since the Renaissance and where secular figurative painting was reaching its end just as it was beginning in Palestine.”

Saig – who had built his reputation on his large icons and art restoration skills – started to make oil paintings of peasants, landscape points of the local countryside, and scenes inspired by historical events.

(Untitled)

Painting by Tawfiq Jawhariyyeh

via Palestinian Art book

In Kamal Boullata’s book, Palestinian Art, writes:

“As elsewhere in the world, the transition from religious to secular painting in Palestine was a major step in the development of the language of art.

The change in emphasis did not come as a result of the artist's conversion from religious belief to a secular view nor did it come about simply as a result of being exposed to new tools and methods of painting. Rather, it came as a result of understanding the new knowledge disseminated by the changing world around him or her and by what the artist does with that knowledge.”

Al Quds / Jerusalem remained the center for this developing “national form of visual expression” as the local iconographers incorporating these new ideas were leading the way.

Saig’s studio there was also an important place for artists to hang out and develop. This included the Jawhariyyeh brothers – including Wasif Jawhariyyeh, who would go on to become a musician/poet, and Tawfiq Jawhariyyeh, who would become an photographer/painter.

WWI + British Mandate

1914 - 1922

A mix of historical and art context for a formative period of transition in Palestine.

Ottoman Empire Transition

Since 1516, the land of Palestine had been under control of the Ottoman Empire over the course of four centuries.

Ayşe Betül Aytekin describes this in an article for TRT World as “a period marked by peace, harmonious coexistence and flourishing of local culture.”

In particular, it was a time when three monotheistic religions coexisted without conflict.

“For the Ottomans, Palestine’s importance stemmed from its historical capital Jerusalem, which is regarded as Islam’s third holiest city after Mecca and Medina. For the Ottoman dynasty, which already held the Islamic Caliphate, the stewardship of these lands was viewed as a sacred duty.

And yet, given Jerusalem’s position as sacred to the two other Abrahamic religions, it never tried to disturb the harmony that existed between believers of different religions who lived in the Holy Lands.”

However, the Ottoman Empire had weakened by the end of the 19th century, including losing areas like Algeria, Tunisia, and Kuwait.

In 1914, World War I began. The Ottoman Empire fought as part of the “Central Powers” aligned with Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Bulgaria. They faced the “Allied Powers” of France, Russia, Italy, Romania, Canada, Japan, Great Britain, and later the US.

In 1917, the British invaded Palestine, where significant fighting took place in Gaza at first. The British then headed towards Al Quds and eventually won. In December, mayor Hussein Salim al-Husseini announced the surrender of the city.

Surrender of Jerusalem to the British Battalion, on December 9, 1917

Painting by Nicola Saig

via Institute for Palestine Studies

Husseini Surrender

Painting by Nicola Saig in 1918

via Palestinian Art book

One of the paintings that Nicola Saig did shortly after was based on a photograph taken of the moment of the city’s surrender. This work is described as a turning point in Saig’s career for showing that he was not only able to work within religious iconography but also compete with any modern way of reproducing images of reality, including of those in the local community.

This photo-to-painting rendition was not meant to just be a direct copy. Though Saig clearly had the ability to be fully accurate, he chose to make it his own as well.

“At first sight, the alterations introduced into Saig's painting appear to be negligible. They include the reduction in the number of people appearing in the original photograph and the elimination of all the shadows of people stretched in its foreground.

At closer examination, one sees that Saig's slight alterations recompose the group in such a manner as to dislodge the centrality of the British officer in the photograph and show that Jerusalem's mayor has become the central character in the painting.”

British Control & Mandate

The Ottoman Empire did indeed fall, stopping their fighting at the end of 1918, losing control of their territories that included regions of Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, parts of Saudi Arabia, and of course Palestine.

The Treaty of Versailles signed in 1919 formally ended World War I, where The League of Nations was created as an international organization in the guise of maintaining world peace. As Susan Pedersen writes in her book The Guardians: The League of Nations and the Crisis of Empire, this “in effect internationalized colonial rule” and “affirmed rather than repudiated imperialism.”

Hand-colored 1919 photograph in Palestine

via Library of Congress

The League of Nations created “mandates” for countries who were deemed as not yet ready to govern themselves, often with ulterior motives.

With the British Mandate of Palestine, made official by the The League of Nations in 1922, they designated themselves control over the land. As part of it, they adopted the 1917 Balfour Declaration that had publicly declared Britain's position of "the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people."

This was aligned with the goals of the Zionist movement, which had formally been established in 1897 with Theodor Herzl at the helm. As noted in Al Jazeera:

“In the 1880s, the community of Palestinian Jews, known as the Yishuv, amounted to three percent of the total population. They were apolitical and did not aspire to build a modern Jewish state.

But in the late 19th century, the Zionist movement - a political ideology - grew out of Eastern Europe, claiming that Jews were a nation or race that deserved a modern ‘Jewish state’. The movement, citing the biblical belief that God promised Palestine to the Jews, began to buy land there and build settlements to strengthen their claim to the land.”

In the forthcoming years, the British would encourage many Jewish settlers as they pursued a path that sought to implement the goals of Zionism and ignore the actual desires of the Palestinian community.

In The Origins of Palestinian Art, Bashir Makhoul and Gordon Hon write:

“The land on which (Palestinians) had lived and that they had cultivated for generations had become political real estate in a political economy from which they were excluded. Even legitimate ownership of the land carried little weight in that kind of economy. The urban Palestinian political elites that had grown under Ottoman rule and through which the Palestinians had gained some access to the international stage found themselves, under the British, reduced to restless natives.

What was really meant by 'a land without a people’ was a land without a state. The Zionist movement from the beginning understood what was meant by the modern Western construct ‘nation-state.’ They knew that ultimately it did not matter how many people lived there or how deeply entwined their cultural roots were with the history of the land. Without a state, the Palestinians had no sovereignty over their land and, within particular readings of the definitions of this construct, were not therefore a people.”

Art Across Time

In 1920, Nicola Saig did a painting that spoke to both the past and present moment. The goal was to share what Saig had experienced through his life prior to the British Mandate, an equilibrium between the local religious communities.

Caliph 'Umar at Jerusalem Gates

Painting by Nicola Saig, 1920

The painting featured Caliph ‘Umar, described as an early convert of Islam and one of the close companions of the Islamic Prophet Muhammad who reigned from 632 to 634 CE, during the Seige of Jerusalem in 637 CE.

Boullata writes that it brings to mind Byzantine icon depictions of Christ's Entry to Jerusalem, which typically show him in profile riding on a donkey as people go out to greet him at the city gates among palm leaves. “In his attempts to express his experience of Jerusalem’s interfaith harmony,” Boullata writes, “Saig endowed the image of the Muslim conqueror with the Christian traits of the Prince of Peace.”

The painting found great success and was looked at as an iconic representation of Islam's pacifist conquest of the city. The work would go on to be reproduced in schoolbooks.

Art During Mandate

1922 - 1947

After the British Mandate was imposed, life was not ideal. Art, however, did gain steam.

From Students to Teachers

A young artist during this time of transformation for Palestine was Daoud Zalatimo, who was born in 1906 – just before the start of World War I and the Ottoman-British transition.

Zalatimo’s family had a bakery around the corner from Nicola Saig’s studio. He often spent his free time there, finding himself enamored by Saig’s icons and paintings.

At the same time, Zalatimo was friends with the Jawhariyyeh family of brothers, who were also artists. The eldest, Tawfiq, helped nurture his artistic appetite and aptitude.

When the British reign brought in jobs for teachers in elementary schools, Zalatimo got a job at as an art teacher. He started in Khan Yunis and later went to Lydda school, which was closer to home. This provided him a reliable income and proved to elders in his community that art wasn’t a waste of time.

Zalatimo also took summer workshops offered by British art instructors who worked in the Mandate's Department of Education, so he was able to refine his skills. At this time, there were also more art supplies accessible.

The Painter’s Son by Daoud Zalatimo, exact year unknown

As a teacher, Zalatimo saw how his students were inspired by young nationalist poets like Ibrahim Tuqan and Abd al-Rahim Mahmud. Boullata writes that Zalatimo wanted to “demonstrate to his students how visual expression could be as emphatic as written language.”

“The choice of his subject matter, however, had to be carefully thought out if he were not only to avoid the possible wrath of more conventional Muslims among his larger audience, but more importantly to ensure their approval. Zalatimo had to walk a tightrope between his Arab viewers and his British employer. Were he to paint a subject matter esteemed by his compatriots who were vehemently opposed to British policies in Palestine, he could well invite a quarrel with his British employers.

It was in Saig's metaphoric interpretations of historical moments in Islamic history that Zalatimo found an ideal model to emulate. His work, initially displayed as an educational aid within the walls of the school in which he taught, thus expounded themes that were eventually to win the hearts of every Arab of his day, regardless of religious affiliation, and at the same time it did not displease the British who could not see it with the same eyes.”

Zalatimo would draw and paint portraits of historic Arab figures from Islamic history, as well as imagined versions of historic scenes. They successfully caught the attention of students. One of them was a young Ismail Shammout, who Zalatimo taught and mentored.

Other national school principals requested duplicates of Zalatimo’s paintings to display at their own schools, too.

Painting of Sharif Husayn by Zulfa al-Sa’di, 1940

1st Palestinian Art Exhibiton

Nicola Saig’s influence also extended to his first known woman student, who also was an apprentice: Zulfa al-Sa'di.

Sa'di continued to create and her work was exhibited in the Palestine Pavilion of the First National Arab Fair, hosted in 1933 at the Supreme Muslim Council outside Jaffa Gate. This was not just any show, it was the first documented art exhibition in Palestine.

It was a significant moment and impressed national figures who attended. Sa'di presented both oil paintings (portraits, still life, landscapes) and embroidery work – though her paintings received the most attention, which one guest noted made “the images speak.”

Kamal Boullata writes about the show in his book Palestinian Art,:

“Al-Sa’di’s exhibition represented an unprecedented cultural event in which image-making was for the first time officially recognized as a language that could enact an analogous role to that traditionally played by Arabic poetry, that is, in expressing collective aspirations through a personal voice. The Fair's jury granted al-Sa'di the first prize.”

In particular, her portraits deviated from the work of others at the time with close-ups that emphasized – especially when exhibited side-by-side – that “individual human beings and not faceless masses shape history and culture” as Boullata describes. She painted cultural, political, military, and educational figures who had special meaning to both Palestinians and the larger Arab community.

1st Female Professional Photographer

As photography developed, it wasn’t until a couple of decades into the 20th century that the gender of who was behind the lens started to change. Karimeh Abbud is referred to as the first Arab and Palestinian woman to be a professional photographer.

After getting a camera from her father in 1913, Abbud also often accompanied him on work trips to other cities and villages, which provided an opportunity for her to take photographs across the country – including Bethlehem, Tiberias, Nazareth, Haifa, and Qisarya.

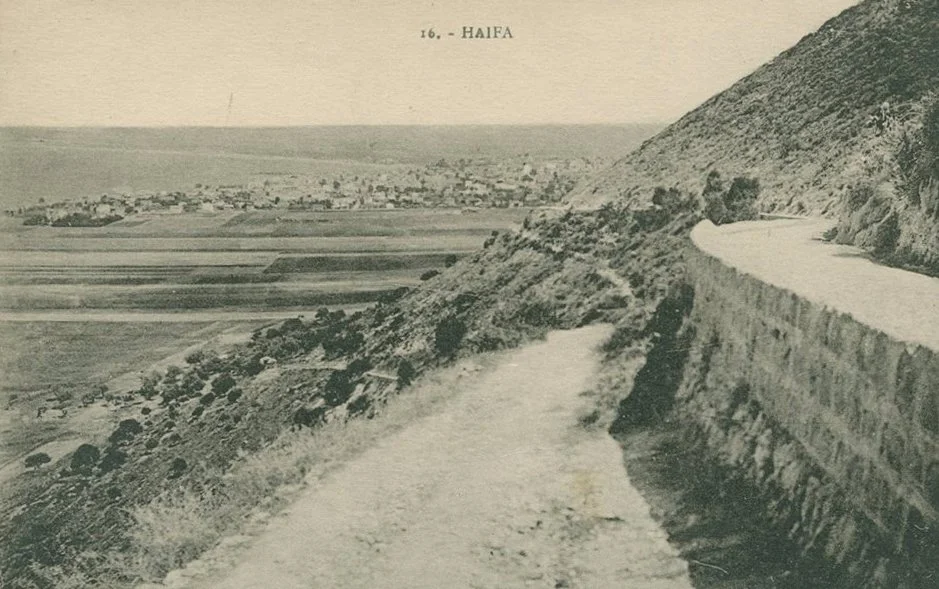

Photo of Haifa by Karimed Abbud

Colorized version of the same photo, as Karimed Abbud was known to add color to her prints

Taking photos of other parts of Palestine would remain a part of Abbud’s work, but it was her photos of people that helped turn it into a feasible career.

Karimeh Abbud behind the lens of her camera

The Institute for Palestine Studies writes that Abbud began to earn money taking portraits of woman and children, and then by wedding and ceremonial pictures. She started in the early 1920s with a studio in her home and later rented out a dedicated photo studio by the early 1930s.

Women felt more comfortable with her behind the lens, including those from conservative families. They even traveled from all over the country to get their portraits taken.

Abbud would go on to establish spaces in other cities, too, with studios in Nazareth, Bethlehem, Haifa, and Jaffa.

She would develop the pictures in her own darkroom, importing printing paper from Egypt. Adding color to her prints also brought her recognition.

Her work was not discovered until around the turn of the 21st century, but we can now recognize and understand the importance of Abbud’s place in photography history.

A mixture of photos by Karimeh Abbud

A Start in Filmmaking

Dubbed as the first Palestinian filmmaker, Ibrahim Hassan Sirhan’s first noted work is a 20-minute silent film documenting the King of Saudi Arabia’s visit to Palestine in 1935. He filmed this with cinematographer Jamal al-Asphar. A couple of years later they worked together again – this time on a 45-minute film, Realized Dreams (1937), about Palestinian orphans.

Sirhan also started the ‘Studio Palestine’ production studio in 1945 with another Palestinian filmmaker Ahmad al-Kilani, who had just graduated from a school in Cairo. Their studio made several feature-length films that were screened nationally and in nearby Arab countries.

Al Hambra Cinema in Jaffa, Palestine (1937)

via Library of Congress

As far as movie theaters, the first (The Oracle) had been developed in Al Quds at the start of the 20th century.

But it was in 1937 that the largest theater in Palestine – and all of the Middle East – opened in Jaffa: Al Hambra Cinema.

Al Hambra not only played movies but also hosted other well-known Arab artists for events. This included concerts for musicians such as Umm Kulthum and Farid al-Atrash.

By 1948, there were reportedly 40 cinemas across the country. During this time, films had to be approved to watch by the British, with mostly Egyptian and American films being played at the time.

Historical Context: The Arab Revolt

After the Ottoman Empire had ruled for centuries in finding co-existence between civilians of multiple religious faiths, that shifted after World War I and the implementation of the British Mandate.

Art may have grown during the time of the official Mandate period from 1922 to 1948, but there was also a rising of tension between Arabs and Jews.

Britain ushered in large numbers of European-Jewish settlers during the 1920s from the start of their rule. The Balfour Declaration had made it clear that Britain’s commitment was to Zionism and the establishment of a Jewish state in a land that had a majority Arab population.

The Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question writes about the continued influx of immigrants, and the impact, around the time of The Great Depression:

“In Palestine, as elsewhere, the 1930s had been a time of intense economic disruption. Rural Palestinians were hit hard by debt and dispossession, and such pressures were only exacerbated by British policies and Zionist imperatives of land purchases and ‘Hebrew labor.’

Rural to urban migration swelled Haifa and Jaffa with poor Palestinians in search of work, and new attendant forms of political organizing emerged that emphasized youth, religion, class, and ideology over older elite-based structures.

Meanwhile, rising anti-Semitism — especially its state-supported variant — in Europe led to an increase of Jewish immigration, legal and illegal, in Palestine.”

This only continued to grow. “In the 1930s, after the Nazis had come to power in Germany, Jewish immigration intensified, reaching its peak in 1935 when 61,000 Jewish immigrants entered Palestine,” notes Al Jazeera.

In addition to wanting to justifiably manage the large swaths of immigration – increasingly through illegal means – and land purchases as part of a Zionist mission, Palestinians wanted an end to the British Mandate. They wanted independence.

The Institute for Palestine Studies writes about the British military’s use of power during this time, leading to a growing dissatisfaction:

“The colonial state intruded upon all manner of daily activities, degrading Palestinians' living conditions and turning the mundane into a site of contest and a pressure point through which to exercise power. The colonial regime converted schools and hotels into military bases, seized crops and livestock, and invaded, assaulted, and demolished homes, villages, and urban quarters.

Quotidian and ritual activities like attending prayers or going to school were made contingent on docile behavior or random circumstance; even funerals were prohibited as potential ‘disturbances.’ Villages were temporarily incarcerated and the movement of goods and persons was restricted and rendered dependent on compliance with state surveillance.

The rebels were determined to build an alternative sovereignty and public realm that would incorporate the Palestinian population.”

British soldiers frisk a Palestinian man in Jerusalem, late 1930s

Photo by Khalil Raad

via Institute for Palestine Studies

One person who played an important role during this time was Izzeddin al-Qassam.

Qassam had his first experience leading his own group of rebel fighters in his home country of Syria in 1919, facing off against French forces in the territory that had also been under Ottoman control. After they were ultimately defeated, he fled to Haifa in Palestine where he was a teacher, imam, preacher, religious official, and more. But he eventually sought to further organize and fight back against foreign control. As noted in the Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question:

“Qassam followed closely the growing menace of Zionism as a result of British support of the ‘Jewish National Home,’ and he became convinced that Britain was the root cause of the problem and that only armed struggle could restrain the Zionist project.”

In November 1935, he and a group of a dozen soldiers fought against a large British army in the forests of Ya‘bad (in the West Bank), a battle in which Qassam did not make it through alive. The next morning, Haifa declared a general strike and there was the biggest funeral the city had ever seen. There was a sizable public outrage.

Qassam played a key part in inspiring a larger rebellion. In 1936, Palestinians called for a general strike, a withholding of taxes, and the closing of municipal governments. Soon, this escalated into larger fighting that saw British forces (along with armed groups of Jewish settlers) clash with Palestinian fighter groups over the upcoming years.

The Martyr Izzeddin-al Qassam

Later artwork by Burhan Karkoutly in 1980

via Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question

Lasting for three years, this period of rebellion from 1936 to 1939 is referred to as the Arab Revolt, the Great Revolt, or similar titles. During this time, around 15% of the Palestinian male adult population was martyred, injured, imprisoned, or exiled.

During this time, the British set a precedent that would be followed by other armed forces in Palestine for years to come. Local fighters who were much more familiar with the land knew how to stay largely undetected. With British soldiers proving inadequate at finding those attacking them, they would instead indiscriminately take retaliation against all Palestinian civilians, businesses, goods, and more in villages of rebel strength.

“Having crushed the revolt, the British rendered Palestinians disarmed, leaderless, defenseless, and their demands for liberation unrealized,” writes Emad Moussa in The New Arab. “The Zionists, meanwhile, were aided to evolve into a semi-state entity with a significant military power that, in 1948, far exceeded in equipment and troops whatever was left of Palestinian resistance and Arab armies combined. The ethnic cleansing of Palestinians was inevitable.”

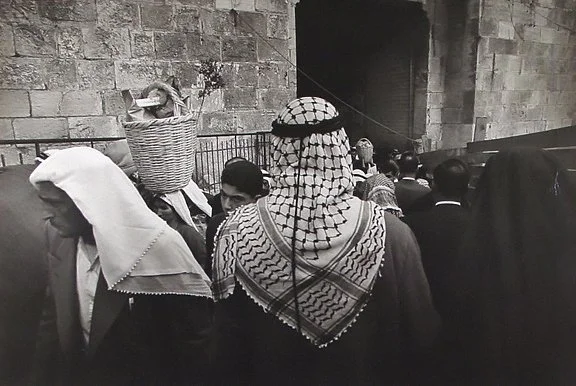

Older photo of a person wearing a keffiyeh

Photographer and exact year unknown

Keffiyeh As A National Symbol

The revolt was also the birth of the keffiyeh scarf being used, starting a long tradition that has kept going ever since.

It’s also spelled in English as kufiyyeh, kufiya, and other variations.

As Samaa Khullar wrote in Everything You’ve Heard About the Keffiyeh Is Wrong for The Nation:

“There is no clear definition amongst historians about what the design of the keffiyeh means, but some Palestinians say each pattern has come to represent a different part of Palestinian life.

The bold black lines on the edge of the scarf are said to symbolize historic trade routes; the fishnet pattern reflects Palestinian ties to the Mediterranean Sea; and the curved lines represent olive trees, one of the agricultural staples of historic Palestine.

The rise of the keffiyeh as a symbol of solidarity, however, mirrors issues of state surveillance that we still see today.

During British colonial rule in Palestine in the 1930s, rural freedom fighters — known as fedayeen — began resisting occupation and were easily identifiable by their head scarves.

As a result, Palestinian men in urban areas, who had previously donned the Ottoman-style fez, answered calls to stand in solidarity with the fedayeen and remove class identifiers by wearing the keffiyeh.

The keffiyeh scarf, still used to this day

Photo by Armando Franca/AP

In 1936, during the Arab Revolt, Palestinian nationalists also began to use the keffiyeh to conceal their identity and avoid arrest by British colonial forces. Much like today’s lawmakers in the United States, the British unsuccessfully attempted to ban the headscarf, because they could no longer identify who was an urban Palestinian and who was a revolutionary. (Their solution to this challenge was to indiscriminately kill everyone.)

As Jane Tynan, an assistant professor in design history and theory at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, told Middle East Eye: ‘From its function in the revolt as a tool to disguise the identity of the wearer from British authorities, the keffiyeh became shorthand for the Palestinian struggle’.”

Community Starting To Form

Kamal Boullata writes that the end of the British Mandate period saw a growing art system.

This was particularly true in Al Quds / Jerusalem, which he notes was the country’s cultural and political center. The recently-established Islamic Museum (est. 1923, at Al-Aqsa) and the Palestine Archaeological Museum (est. 1938) frequently hosted exhibits, performances, and lectures.

In addition, Palestinian collectors and art connoisseurs began to increase – including by Ragheb Nashashibi, Tawfiq Kan’an, Wasif Jawhariyyeh, and Ya'coub al-Husseini. The artists themselves also continued to build community, notes Boullata.

“While the older generations of iconographers and craftspeople continued to meet at Nicola Saig's studio in the Old City, the studios of Jamal Badran and Tawfiq Jawhariyyeh outside Jaffa Gate were gradually becoming a crossroads for a new breed of Palestinian craftsmen, aspiring painters, engravers and calligraphers who finished their studies abroad. They would meet there with collectors and with young and old art connoisseurs.”

He also describes this time as a “contagious period in which the visual arts were beginning to share the prominence that was traditionally reserved for the spoken or written word.”

Zoom Out:

1800 - 1947

This section pauses the chronology to take a step back and briefly look at the overall evolution of a couple of art forms during this larger period.

An untitled piece of the Dome of the Rock at Al-Aqsa Mosque

Artwork by Khalil Halabi

Initial Palestinian Artists of Record

The works made during this early time of art production often do not get as much attention or recognition, primarily due to lack of images available and sparse information.

Research for this section was particularly guided by Kamal Boullata’s book Palestinian Art: From 1850 to the Present, which is seen as a crucial resource to stitch together the threads of history during this time.

In The Origins of Palestinian Art, Bashir Makhoul and Gordon Hon go as far as to say that “Boullata's meticulous restoration of this period in the history of what was to become regarded as Palestinian art constitutes one of the most important detailed historical works on nineteenth-century Palestinian culture available in English.”

Several images in the previous sections were also used from Boullata’s book, as there are very limited images online when you search for the work of artists from this era.

The Mosque's Courtyard

Painting by Daoud Zalatimo, year unknown

via Palestinian Art book

In tracing the journey from the icon paintings to secular work, one can see the evolution of paintings as Palestinian artists entered the 1900s.

In order to adapt with the times as photography became a popular form of image-making, paintings also began to touch on more modern subjects of people and events. This would soon serve to be relevant to the art that followed.

A notable pattern that can also be seen is how artists passed down lessons, tracing a through-line between generations. After Nicola Saig set the precedent in teaching so many artists like Zulfa al-Sa'di or Daoud Zalatimo, that wisdom would continue to be passed down (with new additions and tweaks) to younger artists.

The Profession & Hobby of Photography

Photography as a line of work gained popularity throughout the country during the first half of the twentieth century. There was a need for a variety of photographers who specialized in different fields. From pictures of the holy land for tourists to studio portraits of married couples, soldiers, families, and more – there was plenty of variety to make one’s focus.

“By the time British rule in Palestine drew to a close in 1948, the profession of photography had spread extensively across the country,” says The Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question.

Photo by Khalil Raad

Bethlehem in 1920

via Institute for Palestine Studies

There were several active photographers, like the aforementioned Karimeh Abbud, but one worth looking at as a broader reflection of the period is the aforementioned Khalil Raad.

As the first known Arab photographer in Palestine, Raad had opened his photo studio in 1890 at Jaffa Gate. He continued to make work during the first half of the 20th century.

While many photographers tended to focus on studio portraiture, Raad documented everyday life, political events, archaeological sites, and more.

Photo by Khalil Raad

The Orthodox Christian procession on Easter from the Greek Patriarchate to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in the Old City of Jerusalem, 1910

via Institute for Palestine Studies

The Institute for Palestine Studies, of whom Raad’s archive was later donated to, wrote about his work:

“The photography of Khalil Raad combines an aesthetic value with a historical importance. In his work, there is nothing ‘folkloric’ as was sometimes the fashion in the work of some photographers who were successful in Europe.

On the contrary, his was a vision that showed a considerable sensitivity in its portrayal of daily life. One sees farmers and villages, town scenes all mixed in with portraits of Palestinian fighters, involved since the turn of the century, in the struggle against Zionist colonialism and the British Mandate.”

They explain how European photography at the time – such as with the French – took images where they suggested towns were empty and villages deserted. Raad’s work, instead dispelled “the myth perpetrated by colonialists in Palestine that it was an empty land peopled only by a few savages.”

Photo by Khalil Raad

A girl in traditional clothing standing in a field of wildflowers in springtime in Palestine

As part of Raad’s 1918-35 Collection

via Institute for Palestine Studies