Ismail Shammout

Ismail Shammout is a Palestinian painter who became one of the original artistic faces of the fight for Palestinian liberation – alongside his wife and fellow Palestinian artist, Tamam Al-Akhal. Both stayed very involved with Palestine after getting married and became important figures in the art movement.

The tone was set from Shammout’s first large solo exhibition in 1953, which included his famous Where To? painting of the Nakba.

His artistic voice continued through the establishment of the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) to his Palestine: The Exodus and the Odyssey series of paintings at the end of the 1990s.

However, Shammout and Al-Akhal pursued their efforts from exile – living across nearby countries of Lebanon, Kuwait, and Jordan without the right to return to their birthplace.

Over his career, Shammout’s paintings reflected Palestine of past and present, of hope and despair, of displacement and resistance, of occupation and intifada, of people young and old.

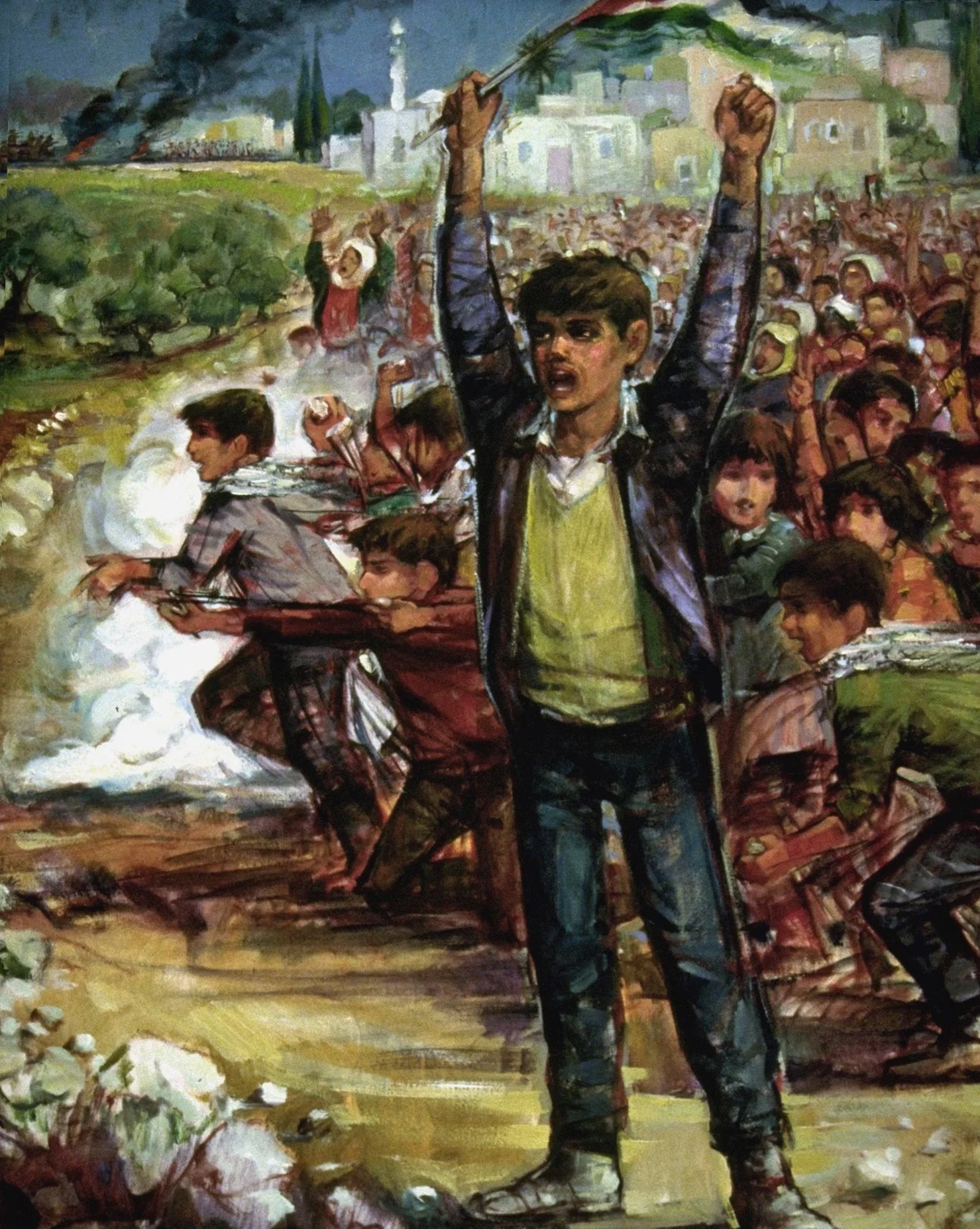

Children of the stones

Schoolboys waiting with stones in a ambush for the occupation soldiers

1984

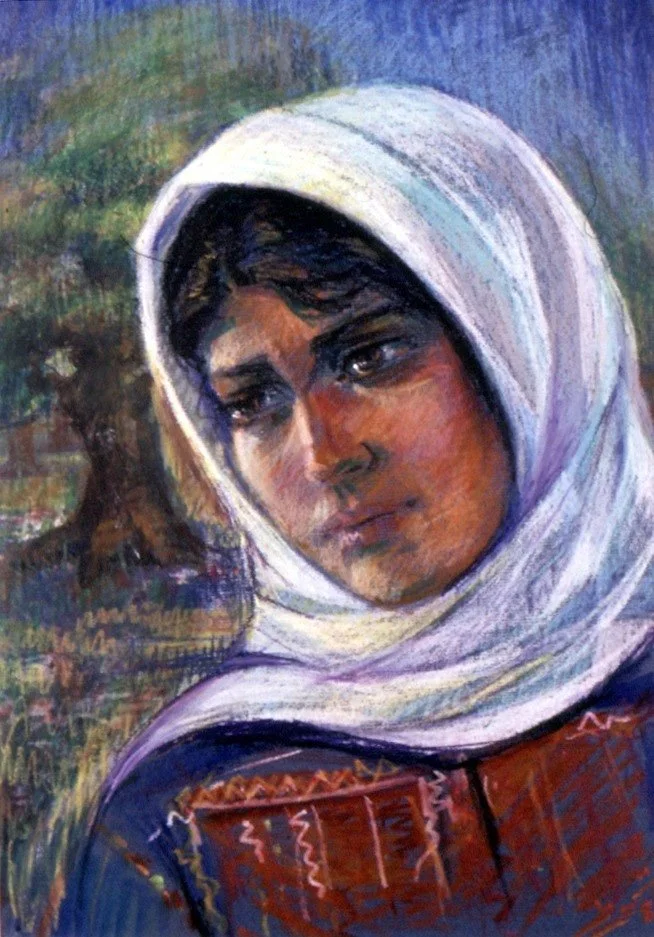

Tamam

The artist’s wife sitting gracefully with a red Palestinian shawl over her shoulders

1964

Portrait

Hind Al Tamimi

1989

Wind and Spring, 1995

Ismail Shammout was born in March 1930 in Lydda, Palestine – one of eight children – during the time of the British Mandate of Palestine.

From the beginning of his life, Shammout was put on an artistic path. As the Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question writes:

“In 1936 he started elementary school, and his artistic talent was spotted at an early age.

His teacher, Dawud Zalatimu, took him in charge. Zalatimu served as an art teacher in Lydda from 1930 until 1948, and his drawings of historic events and nature decorated the school walls.

Shammout was taught by Zalatimu to draw with pencil and ink, to paint with watercolors, and to sculpt in limestone.”

Shammout opened a shop and studio in 1947, at 16 years old, where he would decorate wedding dresses and make paintings of portraits and natural scenery.

This was after he had convinced his religious and conservative father that art could be profitable. His father not only agreed but helped with materials and the space.

However, a year later, Shammout’s life would be forever changed.

A quest for paradise, 1989

Madonna of the oranges, 1997

A hope born in prison

A mother and child from behind the prison cell window

1975

Odyssey of a People, 1980

Face from the Gulf area, 1970

The red veil

The earring is Palestine map adoring the girls ears

1987

During the 1948 Nakba, ‘Operation Dani’ aimed for Israeli forces to occupy the cities of Lydda and Ramla.

In the July attack, Israeli militias invaded the towns and Shammout was forcibly displaced with his large family.

During this operation, Israeli forces martyred hundreds of Palestinians in these towns. In addition, around 60,000 to 70,000 inhabitants of the two towns were forced to evacuate as part of the “Lydda Death March” to Ramallah.

Unfortunately, Shammout’s two-year-old brother fell victim to dehydration as they were not allowed to carry water. He was one of many in the march who did not complete the three-to-five day journey due to exhaustion, dehydration, or disease.

In those initial years, Shammout sold pastries and then taught drawing at refugee tent schools.

Shammout’s family eventually wound up at the Khan Yunis refugee camp in Gaza. While there, he was able to showcase some paintings in a room of the local school in 1950.

Dome of the rock, 1997

Motherhood & olives, 1987

Until dawn

A girl weaving Palestine flag, two kids studying next to their grandparents

1963

The halo

A guerrilla fighter sitting by a tree, a saintly halo surrounds his head

1969

In The Marketplace, 1984

In 1950, Shammout took the train from Khan Younis to Egypt to study at the Fine Art Academy in Cairo.

While he attended classes during the day, Shammout got a job at night with an advertising agency where he worked on Egyptian film posters.

He had instructors that included Egyptian modernist painters Hussein Bicar, Hosni el Banani and Youssef Kamel.

In his first large exhibition in 1953, Shammout hosted an exhibit in Gaza city with his brother Jamil.

At that show, he displayed around 60 paintings – including two especially noteworthy works.

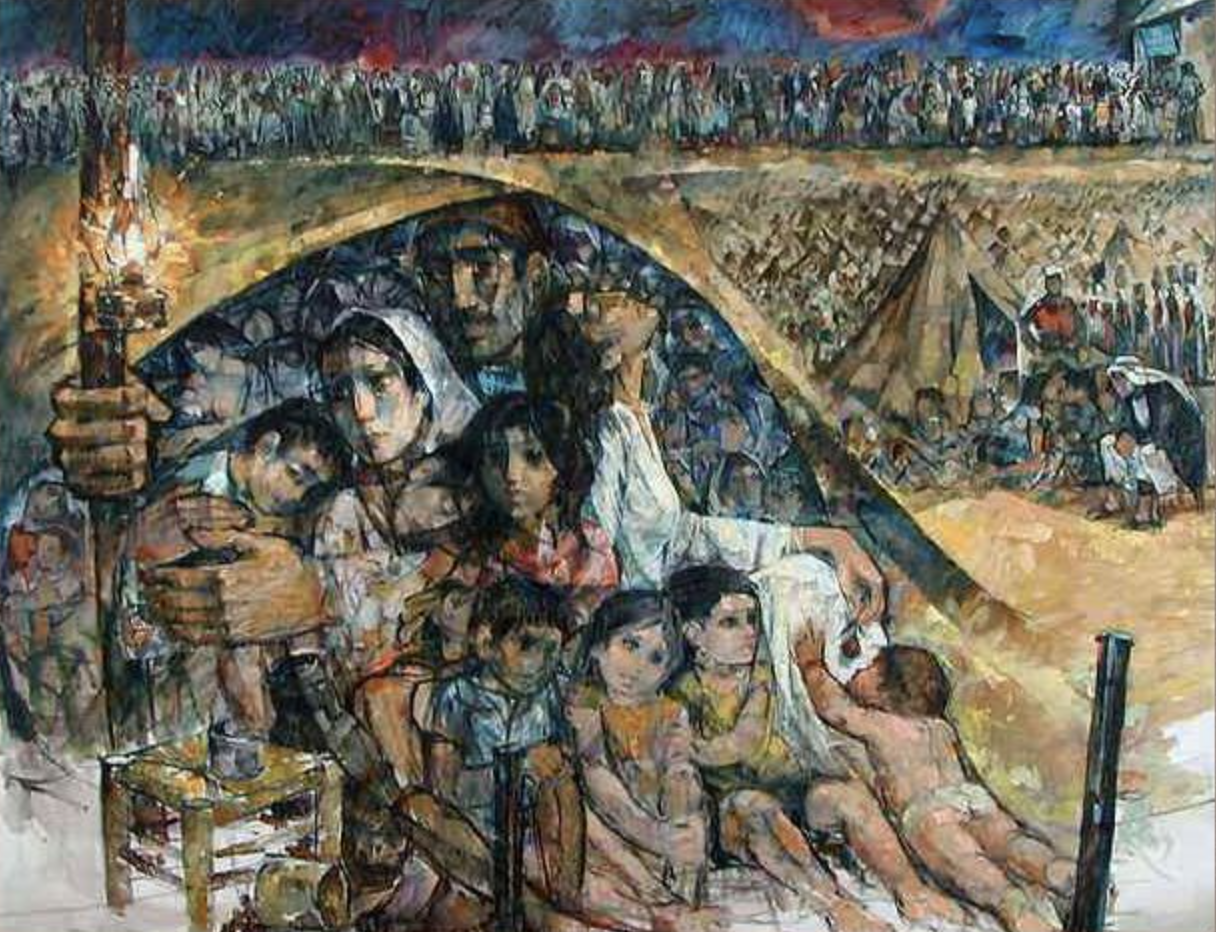

Where To?, 1953

The painting that got the most attention is Where to? – which highlights the 1948 Nakba as a subject matter, showcasing his family’s forced displacement.

It has become one of the most famous works of not just Shammout’s, but of Palestinian art in general. It was later mass-produced and distributed.

A Sip of Water, 1953

The other standout from the exhibit was A Sip of Water, also depicting the forced march from Lydda during the Nakba.

This 1953 exhibit is viewed as the first contemporary art exhibit in Palestinian history that was done by a Palestinian artist on native land.

Palestinian painter Samia Halaby wrote about it in her book, Liberation Art of Palestine:

“The exhibited paintings objectify and socialize a pain that had simmered on a private level.

Refugees in Gaza saw themselves reflected in Shammout’s work and felt relief.

An immense attendance of the general population in Gaza, including those living in refugee camps, overwhelmed Shammout, then studying in Egypt.

This stunning response to the show was a hint of the bottled up hope for liberation. In response, Shammout committed his life’s work to Palestine and the art of liberation.”

A flower from Majdal

Girl in traditional dress (Majdal) against a background inspired from the same area

1970

The old couple, 2000

Palestinian sun bird, 2004

Waiting for his homecoming, 2000

Palestinian springtime, 1987

In 1954, Shammout followed it up with another exhibit: The Palestinian Refugee exhibit in Cairo, Egypt.

It was sponsored by Gamal Abdel Nasser, then Prime Minister of Egypt, who also inaugurated the show. Also present was Yasser Arafat, then head of the Union of Palestine Students, and other Palestinian leaders. The exhibit was well-received and increased recognition.

However, this was not a solo show – the exhibit was jointly held with a couple of fellow artists based in Cairo. This included Palestinian painter Tamim Al-Akhal, his future wife.

Initially after in 1954, Shammout received a scholarship for Rome's Accademia di Belle Arti, where he studied for two years.

During this time, Shammout continued to bring the atrocities of the Nakba into his art – such as the Deir Yassin massacre.

Massacre of Deir Yaseen, 1955

These artworks were especially important, and still are, considering the lack of photographic or video documentation at the time.

After graduating in 1956, Shammout moved to Beirut to live with his brother Jamil. They both worked at the UN Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA), where they established an office for commercial art and book design.

Beirut, 1957

Tamam Al-Akhal had moved to Beirut in the late 1950s as well, originally from Jaffa. In 1959, Shammout and Al-Akhal married.

Adrift, 1998

Newlyweds at the border, 1962

Daily life under occupation, 2004

In Tal Al Zatar Camp, 1970

Mulberry in season, 1996

At Erez crossing (the blockade), 1997

At Erez crossing (the queue), 1997

When the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) was formed in 1964, Shammout soon stepped into a new role.

In 1965, Shammout established the Department of Arts and National Culture of the Palestine of the PLO. One of his initial tasks was designing their first logo.

The logo would be used on several posters, like in the 1965 examples below – taking an unusual shape, with an arched and expanded rounded top attaching to a vertical rectangle.

According to The Palestine Poster Project, the design below is a version of the very first poster the PLO released. The only difference is that the original 1965 poster’s Arabic slogan translated to “We are all sons of Palestine” while this 1967 modified re-print reads “We are all for the resistance.”

(This is seemingly due to the 1967 Naksa, where Israeli Occupation Forces seized Gaza, the West Bank, and additional remaining territories not taken in the 1948 Nakba.)

His wife, Tamam Al-Akhal, also worked with him at the PLO. Their work together included creating designs for many posters, helping art teachers in Beirut and Palestine, and organizing exhibits across the world.

They also created an environment to help artistically train the next generation. In an article by Youssef Naanaa in Palestine Studies, he writes how welcoming Al-Akhal and Shammout were to himself and his colleagues. “The office was like an institute of fine arts, embracing young talents of artists, among whom I remember the artist Adnan Al Sharif, Jamal Afghani, Michel Najjar, and many others.”

The researcher, 1965

Three Tales Three Women, 1970

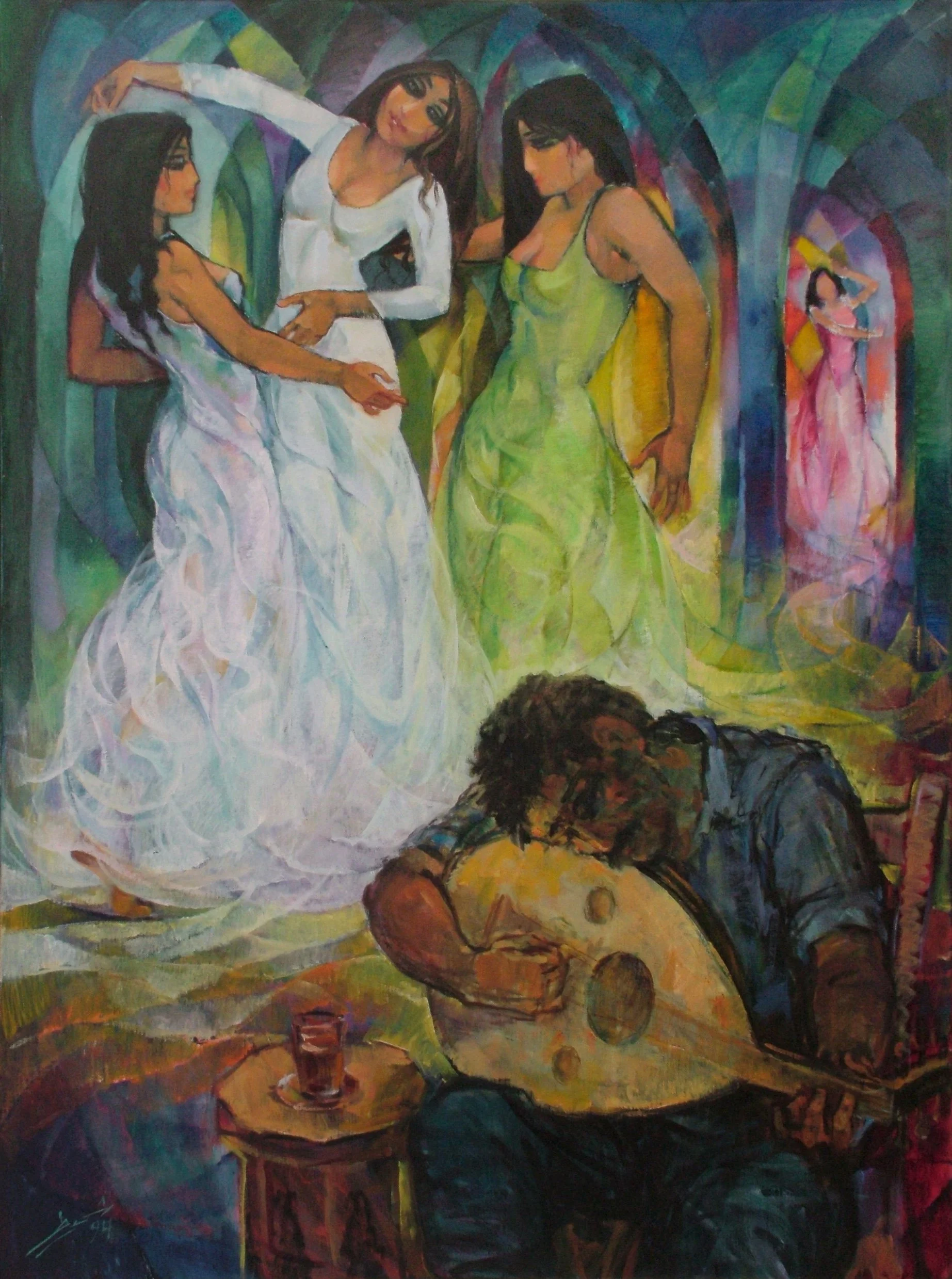

A traditional dance. Dabke

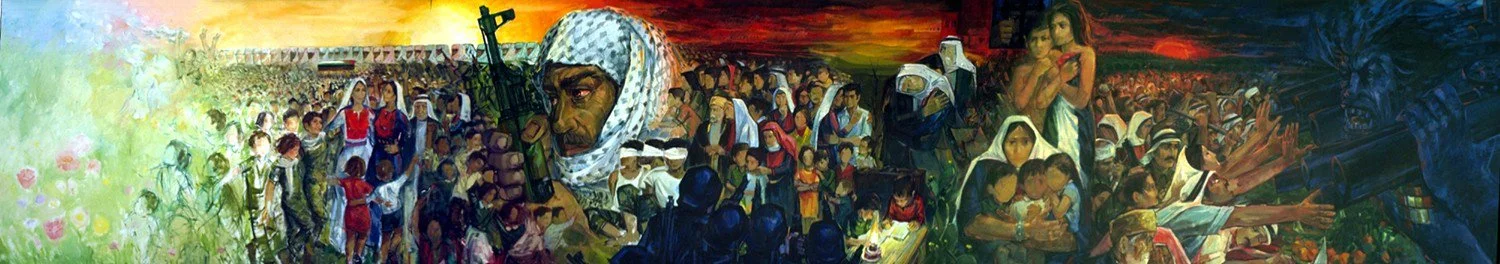

A part of the original mural Life Prevails

1999

Pomegranate

Selling pomegranate and grapes near a gate In old Jerusalem

1989

Amal, 1989

Lady of Jerusalem, 2000

Salwa Miqdadi

Portrait of a family friend

1971

Shammout continued to direct activities for the PLO’s Department of Arts and National Culture until 1984.

In the meantime, he also got involved in other artistic Palestinian efforts.

In 1969, Shammut and other Palestinian artists founded the first General Union of Palestinian Artists. He also participated in founding the General Union of Arab Artists in 1971. (Shammout was the first secretary-general of both until 1984.)

For the General Union of Palestinian Artists, he also set up the Dar al-Karama art exhibit hall in Beirut. It included seasonal exhibitions that included both young artists from Palestinian refugee camps. Also featured were shows in solidarity from Arab and international artists. The exhibit hall also hosted art forums, seminars, and lectures. (During the later Israeli invasion of Lebanon in 1982, the building was destroyed but some work was managed to be rescued.)

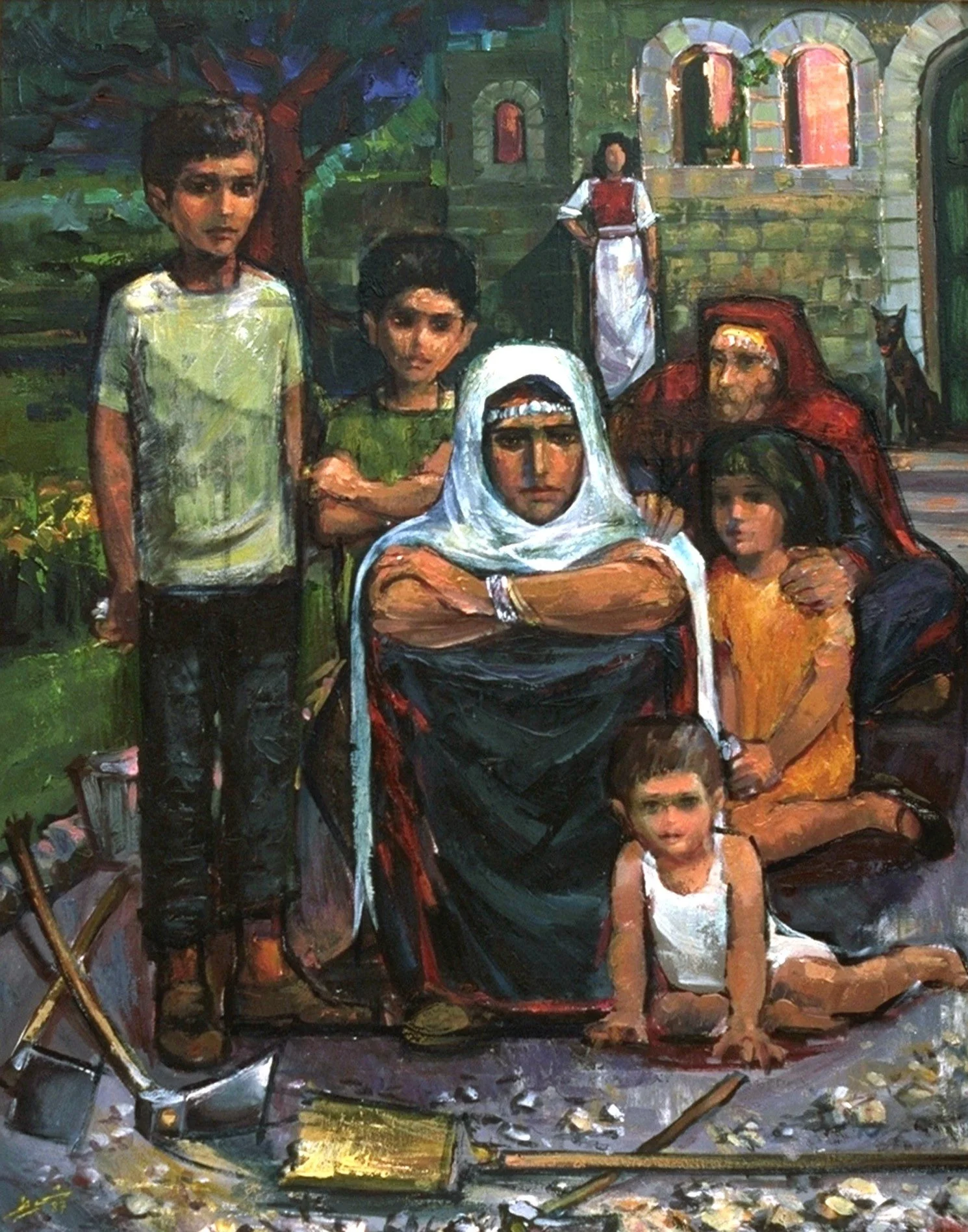

The maiden and mother

1984

Kuwait 91

Palestinians in Kuwait after its liberation and the attempt to persecute them

1993

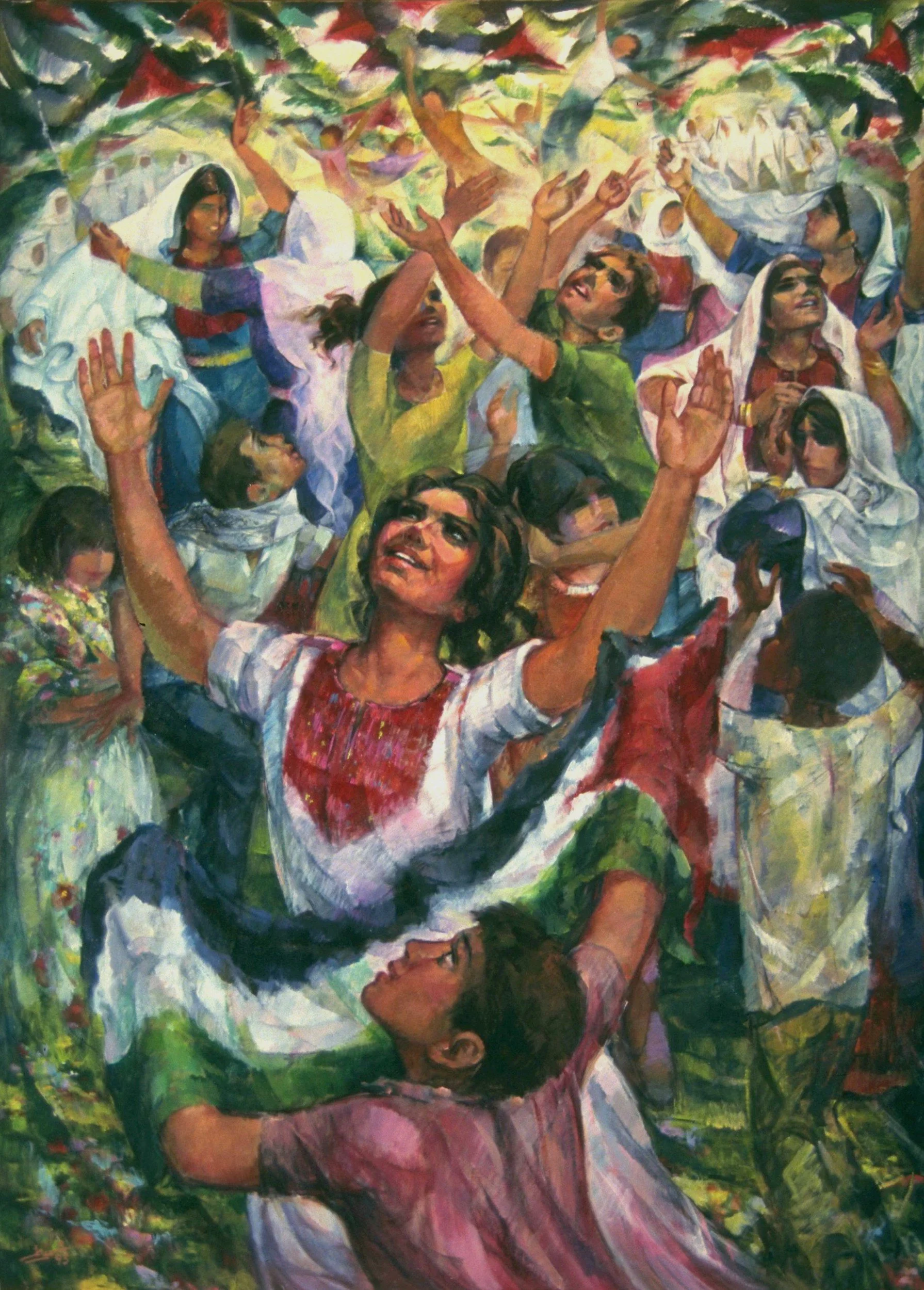

Joy

The traditional Palestinian dance (Dabke)

1993

The berry bride

A young woman in a green dress holding a basket full of berries

1965

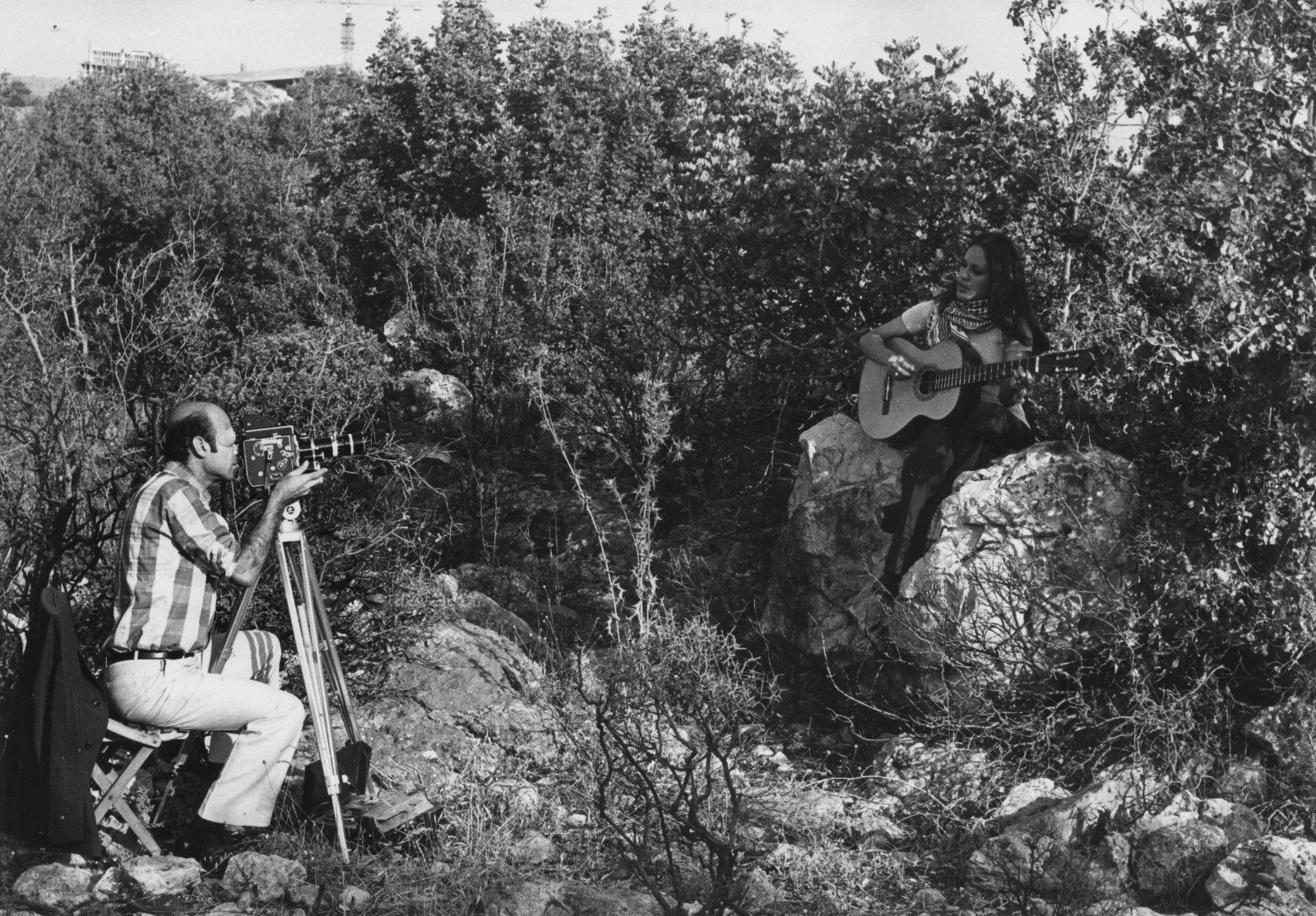

He also worked on a few short films in the 1970s, which are mostly unavailable to watch. However, one is available below – listed as The Urgent Call of Palestine (1973).

It featuring the Palestinian singer Zeinab Shaath, whose family was stuck in Egypt and longing to return to the Gaza home they’d left.

To give some context on her background, In These Times notes:

“Born in Egypt in 1954, Zeinab Shaath was the first member of her family born outside of Palestine. Her father, a Palestinian educator, moved his family to Egypt in 1947 after accepting a job in Alexandria. The Shaaths left their house behind, but they brought along the key for when they would return. Shortly after the Shaaths moved, however, the Nakba erupted; the founding of Israel expelled at least 750,000 Palestinians from their homes between 1947 and 1949, forcing them into displacement and denying their right to return.

Shaath grew up dreaming of finding her own way to contribute to the Palestinian cause. Her love for Palestine was fostered through the stories she heard from her family and their deep ties to the diasporic Palestinian community.”

Shaath’s siblings had gone to study in the US during the 1960s and an older sister, Mysoon, brought Zeinab a guitar. She also brought her Vietnam-era protest records by Joan Baez and Bob Dylan.

Mysoon then gave Zeinab a poem from a coworker’s wife, Lalita Panjabi, with the challenge of putting the words into music within 24 hours. After it was done, Zeinab played it at the Egyptian English-language radio station she worked at. The song would find quick success.

At a Palestinian festival in Lebanon, Ismail Shammout heard her playing the song. Given that he was the Artistic head of the PLO, he envisioned this could be a Palestinian liberation song that could be heard by the Western world – and he thought a film to accompany the music would also be a good idea.

They filmed it on 8mm in the mountains of Lebanon. In it, Shaath sings (in English) while playing a guitar:

“Can’t you hear, the sweet sad voice of Palestine She whispers above the roar of the guns, beckoning to all our daughters and sons. Can’t you hear the agony of Palestine?”

She also released a four-track vinyl record with the PLO Arts department, all in English. This included translating a work of the famous Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish.

However, Shaath refused to take any proceeds and wanted the PLO to have everything – she was just glad to find a place in the movement.

Shammout and Zeinab Shaath filming The Urgent Call of Palestine (1973)

The end of the four-minute film features a brief clip from an interview with Kamal Nasser – a Palestinian writer, poet, and political leader.

Nasser had became editor of the PLO’s publication Falastin Al Thawra in 1972. Soon after, however, Nasser was targeted and assassinated by Israeli special forces in the same year as this film (1973).

The film was then seized in 1982 during Israel’s invasion of Lebanon, where occupation forces took over the research center, stole boxes of cultural and archival materials, and then destroyed the building.

It was later discovered by Rona Sela – a curator, a researcher and lecturer at “Tel Aviv” University – who found it in the Israeli military archives. However, the original was not shared, only the digital version with the “IDF” stamp at the beginning.

Sela featured it in her 2017 film Looted and Hidden, which incudes it among a larger set of examples of Palestinian archives seized by Israeli forces.

Plains of Beesan, 1997

In Nabatya camp, 1970

Abeer Alshawa, 1997

A Palestinian

Proudly wearing her (Bait Dajan) traditional dress,busy women in the background

1972

The way we used to play, 1987

The flood and the dam

The boy is the future barricade protected by all society

1986

A flower on his grave, 1987

In search for the land

Palestinian people portrayed as seagulls looking for land

1986

Shammout had been dealing with heart problems since the 1970s, which was worsening by the 1980s.

Former PLO colleague and mentee Youssef Naanaa wrote an article in Palestine Studies, where he says:

“During this period, Professor Ismail suffered a health crisis, as a result of which he traveled to East Germany, where he underwent open-heart surgery, after which he returned to Lebanon.

The doctor had reassured him that he would not see him for more than ten years, but he returned to him after two years, so the doctor asked him what happened, he said to him ‘I do not know’ so the doctor inquired about his place of residence, and he told him Lebanon. The doctor replied: ‘We know the reason now.’”

Israel invaded Lebanon in 1982 and expelled the PLO from the area.

Shammout and Al-Akhal made the decision to flee to Kuwait as a result, along with their three sons.

Bilal, 1982

Artist note: “Bilal is our third son. When he was 11 years old, he discovered a painting I had drawn in 1970 for Yazid and Bashar (his two elder brothers) and noticed that he was not present in the painting. So, he seriously protested which made me paint him after the Israeli invasion of Lebanon in 1982, where I promised him a special drawing with his two brothers. I painted him as if he was sitting in the studio, with two paintings of his brothers and mother in the background and a painting bearing my personal picture on which the tip of my baldness appears.”

During his time in Beirut leading to the ‘82 invasion, Shammout had made several paintings of Palestinian refugee camps there.

In Tal Al Zatar Camp, 1970

In the late 1980s, Shammout covered the first Intifada – a seven-year Palestinian uprising that began in 1987.

Painting from Kuwait, his work captures the spirit of the rebellion across many paintings. He continued to return to this intifada as a subject matter in the years to come.

Survival during Intifada, 1989

The breakthrough, 1988

The fortress, 1989

Continuance, 1988

Intifada, 1988

Later, the family would then have to endure the 1991 Iraqi occupation of Kuwait and the subsequent U.S.-led Gulf War (‘90-91), forcing them to move again in 1992.

After a couple of years in Germany, Shammout and Al-Akhal finally settled in Jordan in 1994. They would stay there for good after.

In the late 1990s, after the Oslo Accords, they were able to visit their respective Palestinian hometowns of Lydda and Jaffa.

Love and Homeland, 1997

While there, Shammout had a warm reception in his hometown of Lydda. However, he noticed his original home had since been overtaken by Israeli settlers.

The trip motivated him to work on many paintings – including a series of large-scale works that he hoped could be permanently displaced in his home country.

Between 1997 and 2000, the married couple created 19 mural-like paintings for the series: Palestine: The Exodus and the Odyssey.

To The Unknown, 1997

For Survival, 1999

Homage to the Martyrs, 1999

The Beirut-based visual arts institution Dalloul Art Foundation writes about The Exodus and the Odyssey series:

“Scenes from Palestinian history overlap in multidimensional compositional narratives, using visual strategies reminiscent of Mexican Muralism.

In cinematic succession, Shammout presents a joyful depiction of life in the 1930s, The Spring That Was (1997), followed by the exodus, the struggle, and the resistance, and paying tribute to Palestine’s fallen martyrs.

The Spring That Was, 1987

The series concludes with The Dream of Tomorrow (2000), a hopeful image that portrays children flocking to a benevolent Mother Palestine, gathering flowers and fruits for her as birds fly freely overhead.”

The Dream of Tomorrow, 2000

In 2003, Shammout and Al-Akhal came back to Beirut – one of several trips back over the years – to launch an exhibition featuring these works.

Resistance, 1999

Palestinians... Refugees, 1998

The Road To Nowhere, 1998

Intifada, 2000

The Nightmare And The Dream, 1998

Life Prevails, 1999

In June 2002, Shammout had traveled to Al Quds to visit his original teacher and mentor Dahoud Zalatimo, who at that time was near death. Zalatimo’s granddaughter, Fadwa, told The Electronic Intifada that it was a very emotional event. Shammout expressed his gratitude and they both cried.

Shammout continued to make many pieces in the early 2000’s all the way up until his passing in 2006, after dealing with ongoing heart issues.

His tombstone quoted Mural, a Mahmoud Darwish poem: “I have defeated you, O death of the arts.”

(Tamam Al-Akhal is still alive today and a separate feature on her work will be coming to this site in the future.)

The sea and us, 1984

Under the shade of the olive tree, 1998

Two sisters, 2004

Aziza, 1989

In 2014, Dar Al-Kalima University College of Art and Culture, in the West Bank, started a contest and award in his name.

“Ismail Shammout Award in Fine Art was created in 2014 to honor the late Ismail Shammout and his contribution to the Palestinian art and culture and to celebrate the creativity of young artists and motivate their artistic engagement in subjects relevant to the Palestinian struggle for freedom, equality, dignity, self-determination, and the right of return.”

The annual award is still ongoing, a decade later.

Shammout’s art and story of have continued to be shared aover the years – such as in Ramallah in 2017 at an event to celebrate his life. It took place in conjunction with the release of a biography Al-Akhal wrote about their story.

He left behind a legacy as one of the premiere and founding voices of Palestinian art and history.

We will not leave, 1987

We are the wall, 2004

Waiting for the player (to play the tune of victory), 1984

The dream, 1994

Self-portrait, 1985

He will be back, 2005