Askalan Prison Series

Mohammed Al Rakoui and Zuhdie Al Adawi were both from Gaza and had been fedayeen, or freedom fighters, for the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), which had been established in 1967.

Rakoui and Adawi were thrown in jail at the notorious Askalan prison around the same time, Adawi in 1970 and Rakoui in 1975. While inside, both self-taught artists made work by any means necessary.

Despite restrictions on art materials or it being forbidden to create anything about Palestine, the artists managed to have art materials smuggled in, leading to punishment when caught.

After creating work in secret, with any material they could use, they smuggled out their art. This followed the ongoing tradition of famous and beloved Palestinian poets who smuggled their written pieces out of jail – such as Mahmoud Darwish, Tawfiq Zayyad, and Samih Al Qasim.

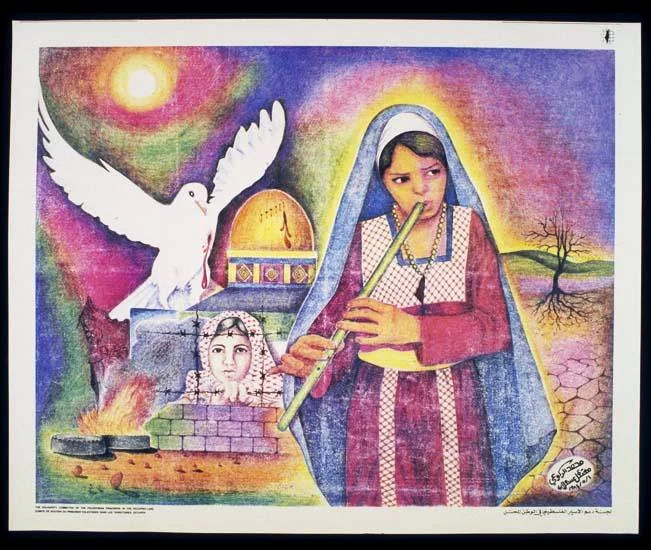

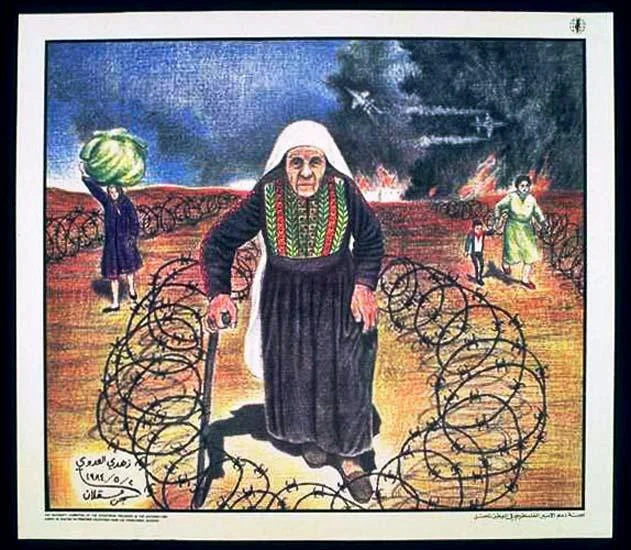

The bright colors in each of their work contrasts the dull and limited colors inside the prison, and act as not only a contrast but an act of defiance to keep their imagination alive.

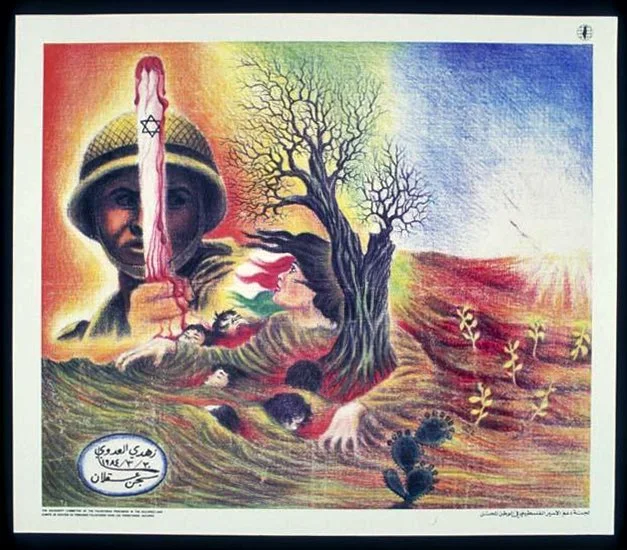

Zuhdi Al Adawi, 1984

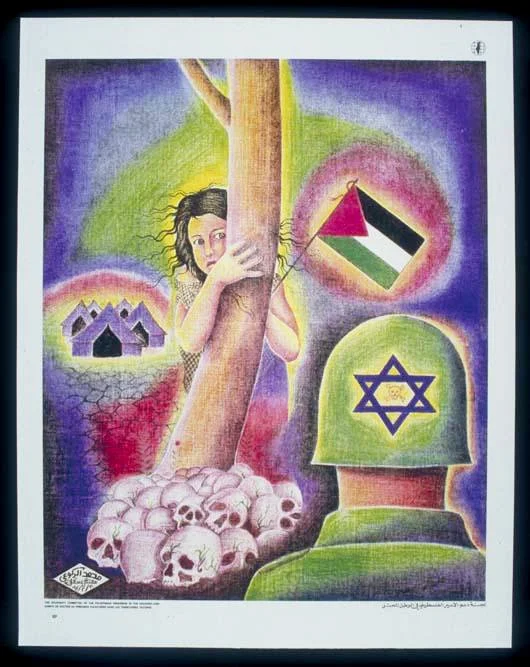

Mohammed Al Rakoui, 1984

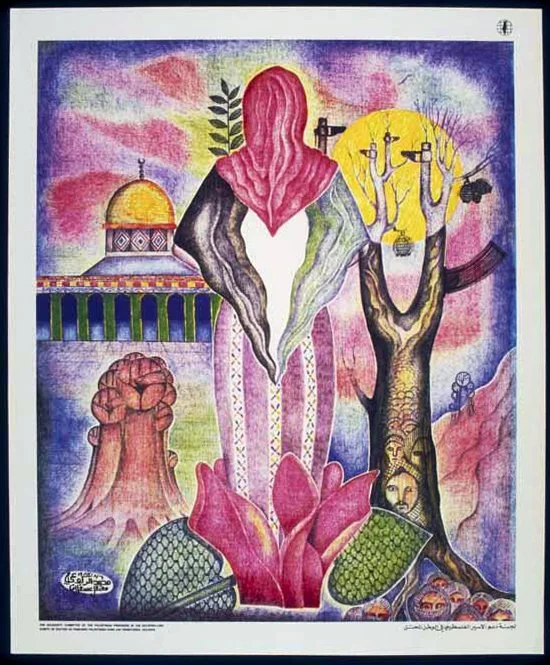

Mohammed Al Rakoui, 1984

Mohammed Al Rakoui, 1985

Mohammed Al Rakoui’s parents were displaced from their Askalan village during the 1948 Nakba, going to the Al Shat refugee camp after (in Gaza). Rakoui was born in the camp in 1950.

In Samia Halaby’s book, Liberation Art of Palestine: Palestinian Painting and Sculpture in the Second Half of the 20th Century, she writes:

“Muhammad channeled his anger at the bitter life of the refugee into organized resistance. He became a fighter at seventeen and successfully carried on until the age of twenty-three, at which time he was captured in Ghazze and imprisoned.

He remembers the intensity of torture during the first three months. Though it continued throughout his imprisonment, its intensity did diminish. His first three months were spent confined to a x2 meter cell. This confinement included beatings and hanging from one wrist. He remembers the screaming - his own and that of others. He remembers being forced to undress suddenly in winter and having cold water poured over him, followed by scalding hot water.

While in jail he found out that his younger brother - only a teenager - had followed in his footsteps and had been killed in Lebanon.”

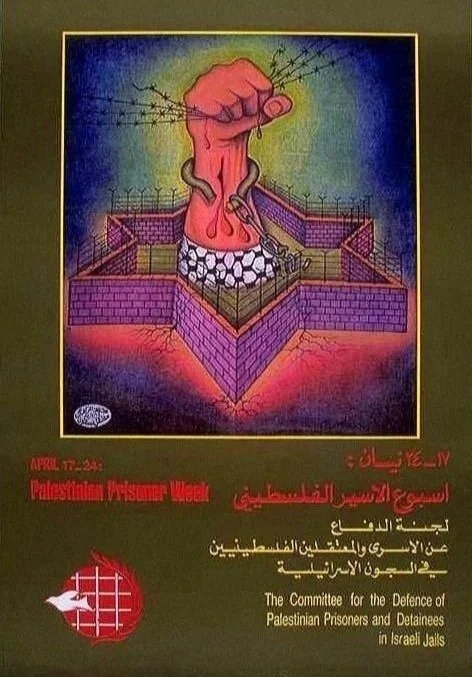

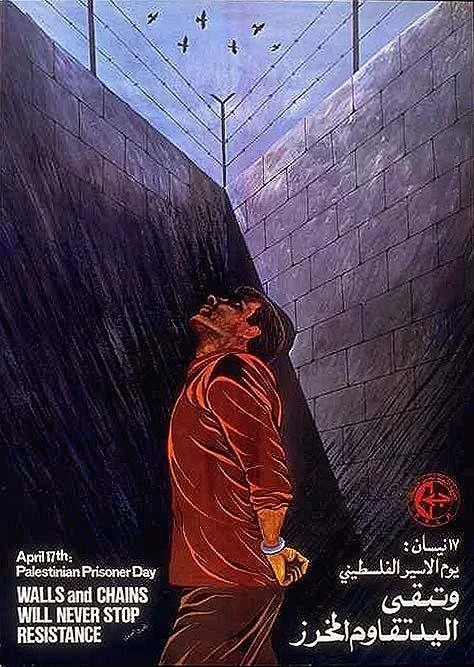

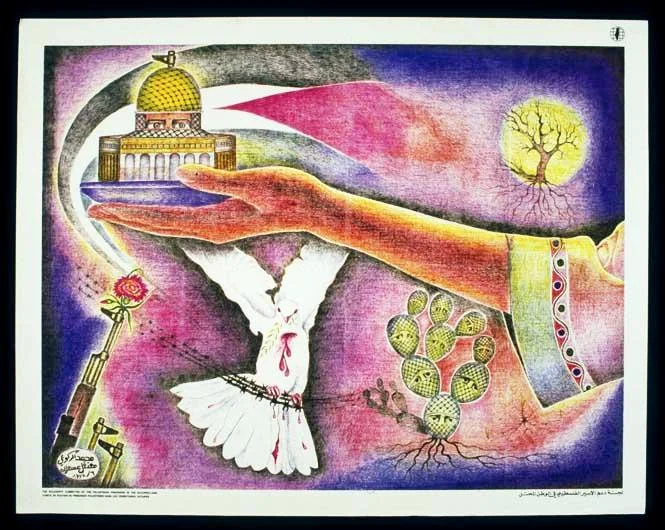

Rakoui’s work was used for posters by various prisoner-liberation groups or resistance factions such as the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP). Additional works of Rakoui were used for several Palestinian Prisoner Week posters as well.

Mohammed Al Rakoui, 1981

Mohammed Al Rakoui, 1984

After being released through the Jibril Agreement in 1985, Rakoui first lived in Lebanon for a year before then heading to Damascus in Syria, where he married and had children. He described to Halaby his life in Damascus “as that of the underpaid and overworked Arab worker.” He had multiple jobs, waking up early and returning home late. In the little time that he had left, he continued to paint.

In describing his art, Halaby says:

“Rakoui's work is symbolist in form. Like most Arab artists, he finds little interest in the full chiaroscuro of the Italian Renaissance. He uses color in a flat manner, paying little attention to reflected light. He gives symbols a sharp clarity by surrounding groups of them with a dark halo.

Handcuffs, the Palestinian flag, the two-finger sign of victory for the revolution, barbed wire, the eagle breaking his chains, the Dome of The Rock, Palestinian village embroidery, the kufiyye, the fisted arm raised in determination, the peasant dress, the village, prison bars, birds in the colors of the revolutionary flag, the horse as symbol of the revolution, and many other such images are artfully combined to speak the language of Palestinian resistance.”

Mohammed Al Rakoui, 1983

Zuhdi Al Adawi, 1984

Zuhdi Al Adawi, 1984

Zuhdi El Adawi, 1982

The parents of the other featured artist, Zuhdie Al Adawi, were displaced from their al-Lidd village during the 1948 Nakba, making home next in the Nuseirat Refugee Camp (in Gaza).

Adawi was born in the camp in 1952 and lived there until it was fully destroyed by the 1967 war. He witnessed mass destruction and devastation everywhere, and saw his own mother beaten by Israeli soldiers. At that time in 1967, Adawi became a freedom fighter before being captured and imprisoned, at the time one of the youngest political prisoners.

In prison, he taught himself art. While supplies were prohibited, those who saw him during monthly visits were able to sneak in colored pencils, pastels, and similar items.

As Samia Halaby notes in her book:

“Adawi began making art without any special training. He worked on handkerchiefs that were folded and taken out in the pockets of family members. When handkerchiefs were unavailable, he too used sections of his pillow covers. He said that whenever the guards discovered them, they would place the artists in solitary confinement for one full week.”

Zuhdie Al Adawi, 1980

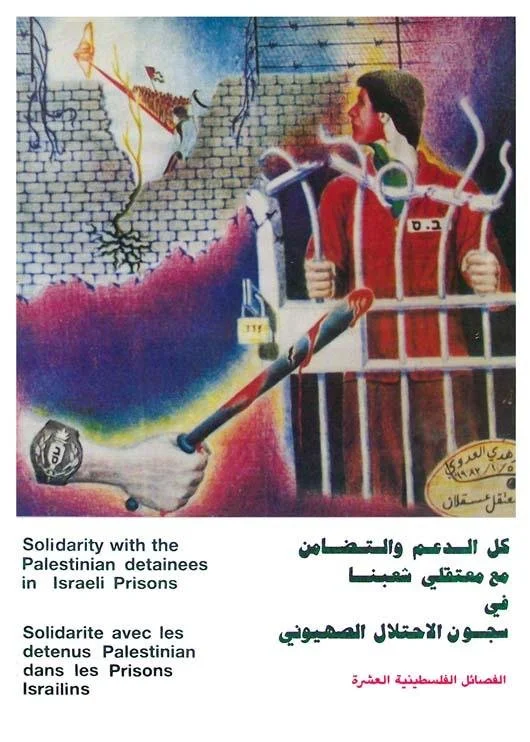

Adawi work was turned into posters, too.

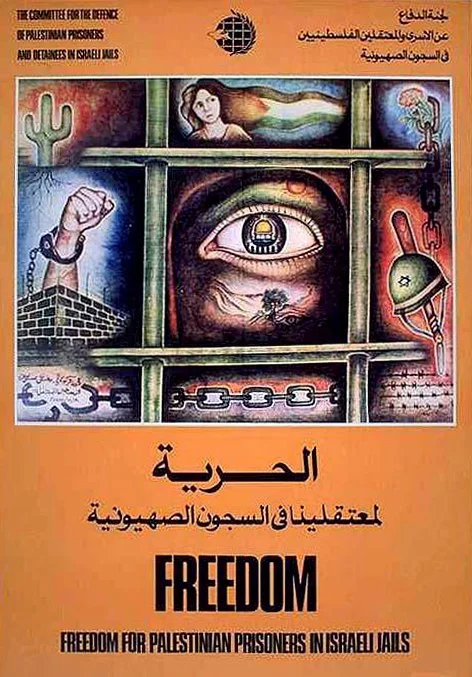

This includes a Palestinian Prisoner Day poster for the PFLP (above) or a 1982 poster for the PLO (below).

The PLO poster features four languages – English, French, and Arabic – as calls for international solidarity.

Zuhdi Al Adawi, 1982

Halaby also describes Awadi’s journey finishing his time in prison:

“An exhibition of the art of Palestinian prisoners at the Soviet Cultural Center in Damascus took place one month before Adawi left prison. After the exhibition, prison authorities began to search visitors thoroughly, and Adawi had to invent new ways to smuggle his art out.

He was sent to Lebanon in 1985 when a prisoner exchange agreement was completed between Israel and the PLO. In Lebanon he studied for six months at the Center for the Visual Arts. Shortly thereafter, Adawi moved to Damascus, where he found a more suitable environment and began a new period of experimentation.”

Mohammed Al Rakoui, 1983

Zuhdi Al Adawi, 1984

Zuhdi Al Adawi, 1984

Zuhdi Al Aduwi, 1984

Site note: Samia Halaby said of this painting:

“Adawi combines symbols of imprisonment and patriotism into a coherent image. Through handcuffs and prison bars there appears a woman whose hair is arranged in the colors of the revolutionary flag. She wears a red kufiyye, a scarf symbolic of the Palestinian revolution. Arched doorways, a flame, lightning, crowds of people, chains, and the cactus plant, the latter symbolizing patience and endurance, complete the picture.”

Zuhdi Al Adawi, 1984

Mohammed Al Rakoui, 1985

Their art from this series was featured in Palestinian Art Behind The Bars, a booklet of prisoner artwork of mainly Rakoui and Adawi.

It was published in 1984 by the Palestinian Prisoners Committee, both in Arabic and English. It is no longer in circulation, but was made available online for download and distribution by the Samidoun Palestinian Prisoner Solidarity Network in 2016.

In addition to featuring the artwork, the booklet shares information on the terrible treatment of prisoners using various forms of physical and psychological torture, all with advanced technology. It also describes the inhumane, crowded, unsanitary, and despicable living conditions Palestinian prisoners are forced to endure. This was happening then and it’s still happening now.

In Grailing Anthonisen’s published 2019 thesis, A History of Palestinian Uprisings through Prison Resistance since 1967, he writes:

“For many Palestinians, art and poetry were a continuation of their struggle. Light and colours became acts of defiance. The art and poetry created inside prisons, while created by individuals, contributed to a collective body of revolutionary culture.

Art and poetry appealed to a sense of resistance and defiance, in spite of violence, brutality, and material constraints, while contributing to a sense of national belonging. They were created by and for the Palestinian community inside and outside prison.”

Cover for ‘Palestinian Art Behind The Bars’ booklet, released in the 1980s by the Committee for the Palestinian Prisoner

These pieces were also part of the first museum exhibition in the United States devoted to contemporary Palestinian art. The 2003 “Made in Palestine” exhibit took place at the Station Museum in Houston, Texas.

The exhibit included a variety of artists across the West Bank, Gaza, and the ‘48. It also included some artists in the diaspora across Syria, Jordan, Germany. The aforementioned Samia Halaby consulted for the show, which was curated by James Harithas.

The exhibit also traveled to New York in 2006, which Adawi was present for. The Electronic Intifada describes the excited crowd at the Bridge Gallery opening:

“Traditional Palestinian food was served throughout the night from Tanoreen restaurant in Bay Ridge, and the mood was one of celebration and dancing. Almost 2,000 visitors were estimated to have attended the opening of the Made in Palestine exhibit, making the place feel, at times, as claustrophobic as Kalandia Checkpoint… minus Israeli soldiers with guns.”

The show also traveled to Vermont and San Francisco.

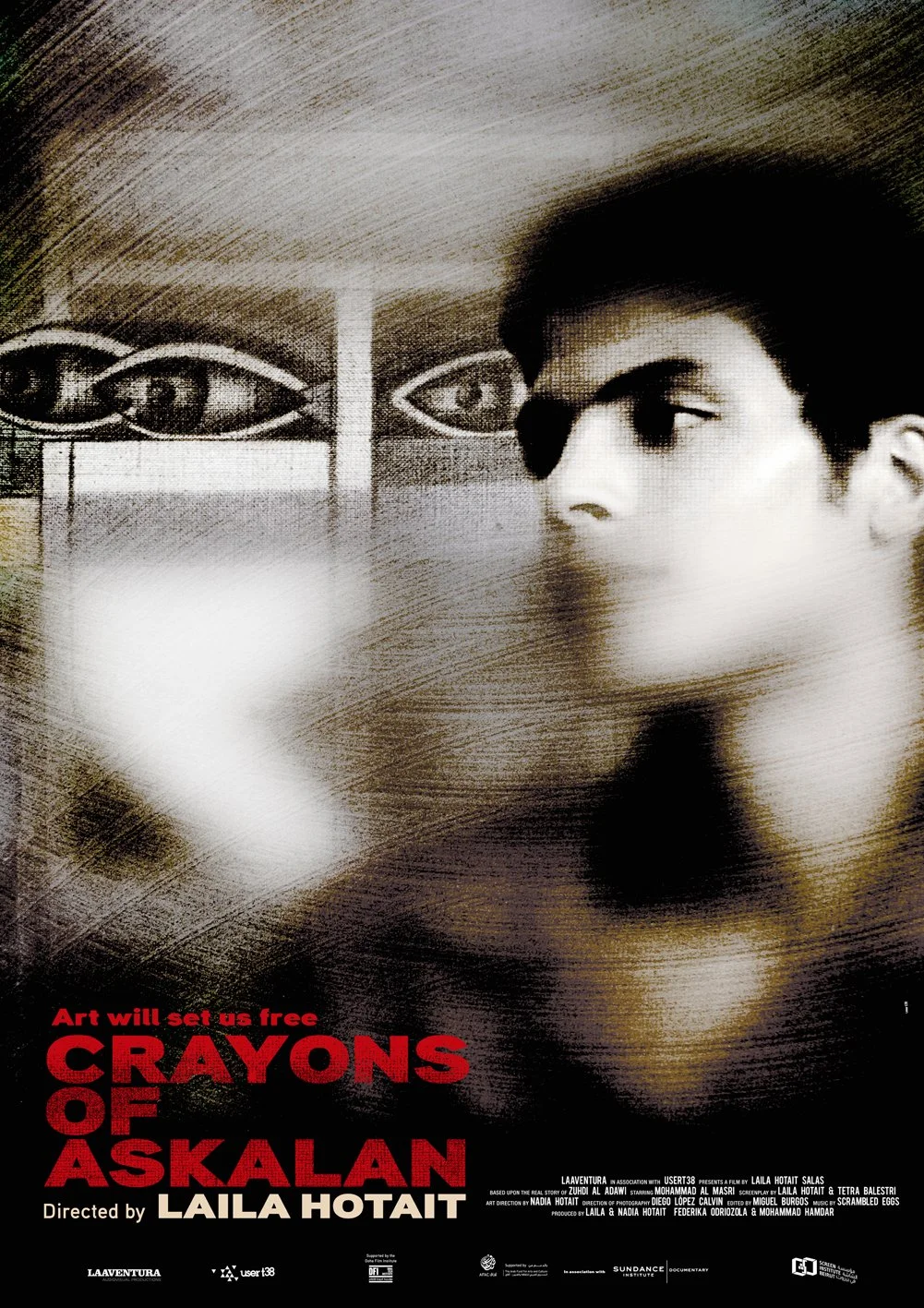

Separately, a documentary on Adawi was released in 2011 called Crayons of Ashkelon – أقلام من عسقلان, though VA4P was unable to find a way to watch it at this time.

Rakoui and Adawi’s art was, and remains, a visual manifestation of their perseverance in prison – a continuation of their fight for freedom under occupation.

To this day, other Palestinians have been continuing to teach themselves how to make art in prison with any materials available.

One recent example is Ghassan Al Azzeh, who was imprisoned at 16 years old, almost the same age as Adawi a half-century before.

After later being released, Azzeh told Al Jazeera that an older group of Palestinian artists prisoners took him in. “They taught me so much about making art in prison. We didn’t have real art materials, so they showed me how to make brown sugar packets into beautiful portraits.”

When Azzeh was later released, he continued the craft and embraced the materials. “I like to take recycled things and make them into something new. Art can be a way of resistance – it’s my way of resistance,” he said.

Last Updated

2024

Image sources

Palestine Poster Project

Background research sources

Samidoun: Palestinian Prisoner Solidarity Network

Station Museum

Houston Press / Mutual Art

Al-Awda New Jersey

Al Jazeera